The Hollywood Reporter reviews GEP friends’ THE TRANSFIGURATION:

An orphaned African-American teen leads a secret life fed by vampire lore in Michael O’Shea’s indie debut, premiering at Cannes in Un Certain Regard.

Wide-ranging references to vampire mythology in literature and cinema are scattered throughout writer-director Michael O’Shea’s low-key but absorbing first feature, The Transfiguration. But what distinguishes this stripped-down anti-horror film — set amid the housing projects and lonely beachfronts of the Rockaways in Queens, New York — is its absence of the supernatural. While death by bloodsucking is very much a factor, this is actually a subdued, contemplative drama about the lingering trauma of grief and the efforts of an introspective teenager to invent an invulnerable persona to shield and ultimately release him.

Genre consumers addicted to fast-cut thrills and gory excesses are unlikely to remain glued to this unapologetically downbeat film, though its acknowledgement of influences from Murnau’s Nosferatu through George A. Romero’s Martin and Kathryn Bigelow’s Near Dark to Tomas Alfredson’s Let the Right One In will stoke some interest in serious aficionados. The core audience is more likely to be admirers of austere indies that bring an unvarnished gaze (and unhurried pacing) to the wounded casualties on the far fringes of metropolitan life.

In that respect, the relatively untrafficked screen setting, a low-income area still somewhat dazed by the physical and economic battering of Hurricane Sandy in 2012, with Manhattan both a subway ride and a world away, adds authenticity. Subtext themes of poverty, race and class are ingrained in the visuals, without the need for commentary. And cinematographer Sung Rae Cho’s tack of viewing the protagonists in wide-shot exteriors that emphasize their solitude in this environment — particularly the shoreline and boardwalk scenes — adds to the melancholy feel.

The movie opens with a sly bit of audience deception in a public restroom, where the sounds emerging from behind a cubicle door and the two pairs of feet visible underneath give the impression of illicit sex. But 14-year-old Milo (Eric Ruffin) is soon revealed to be chowing down on the neck of a facility user, before lifting the dead guy’s cash and making a calm exit.

An introverted black kid bullied at school and called a freak by local gang members, friendless Milo lives under the guardianship of his older brother Lewis (Aaron Clifton Moten), a military vet who spends his days planted on the couch watching mindless TV. It’s suggested that Lewis was once a gang member, but depression over their mother’s suicide has taken its toll on both brothers. Their father died when Milo was eight.

Milo’s room is his sanctuary, where he watches gruesome nature videos online (scavenger ants devouring prey, lions ripping into an animal carcass) and stashes his loot behind an eclectic stack of VHS vampire flicks, such as The Lost Boys, Fright Night, Nadja and Dracula Untold. (In a jokey reference played straight, he dismisses The Twilight Saga as “unrealistic,” without having seen any of it.) He keeps detailed notebooks full of diagrams and long essays about the rules of hunting and killing.

When a slightly older white girl, Sophie (Chloe Levine), moves into the building to stay with her volatile grandfather, Milo finds an awkward kinship with the fellow orphan, a cutter with self-esteem issues. The film appears to be setting up a twist on the central character dynamic from the terrific Let the Right One In, and alluding to that far superior genre piece does O’Shea no favors. However, the friendship between Milo and Sophie eventually develops in different directions as he purposefully follows a plan that will provide deliverance for her and liberation for him, even if it comes with tragedy.

O’Shea’s storytelling skills sometimes border on the, ahem, anemic, sticking to detached, observational mode when the film could use more muscular forward momentum. But his tenderness toward his characters keeps it watchable. Despite the extreme nature of Milo’s secret life — camping out in Central Park to find victims among the bums that wander the grounds at night — in Ruffin’s internalized performance he is always a damaged boy alone in his pain. The same kind of unshowy rawness characterizes the work of Levine and Moten, yielding several moments that are understated but affecting.

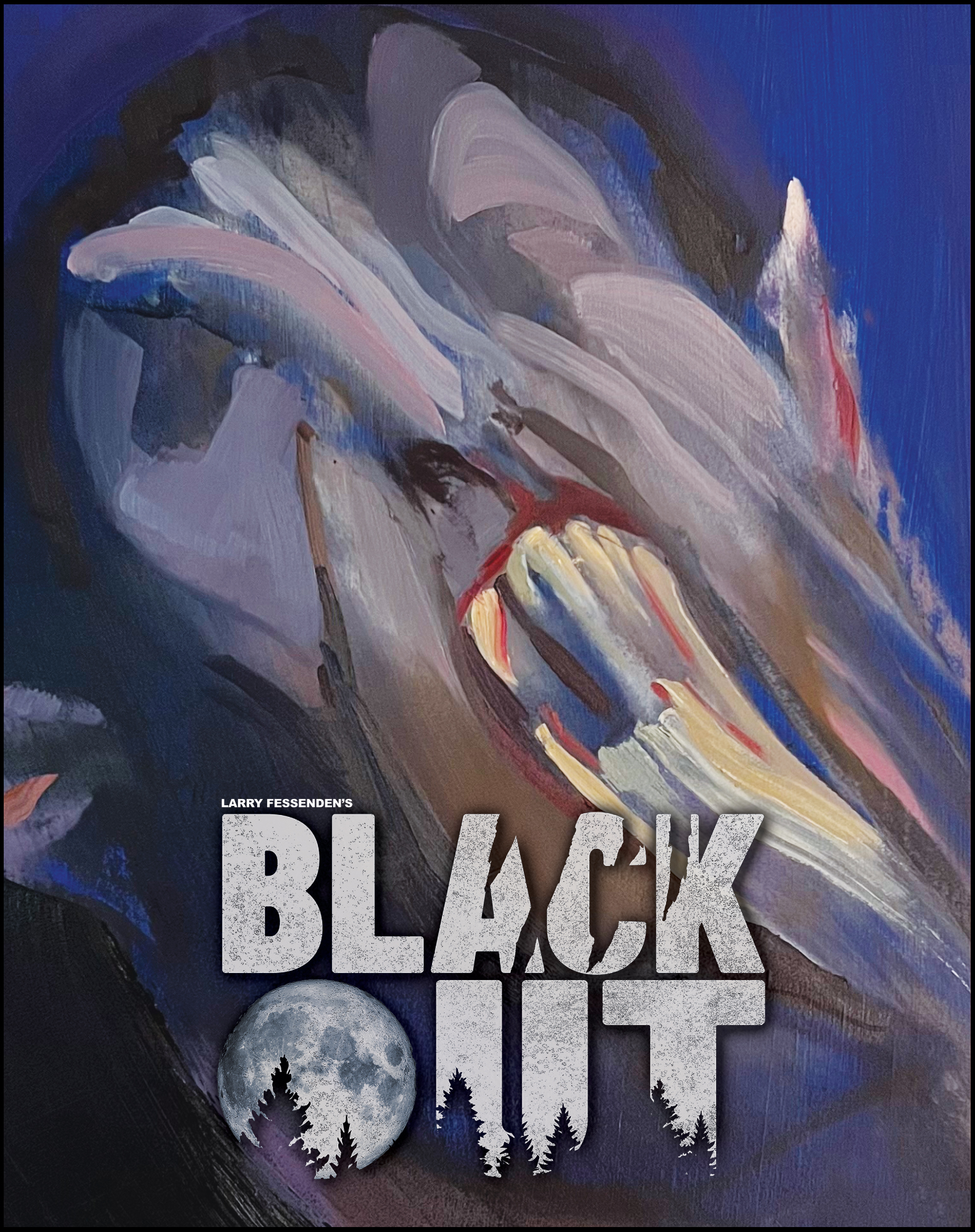

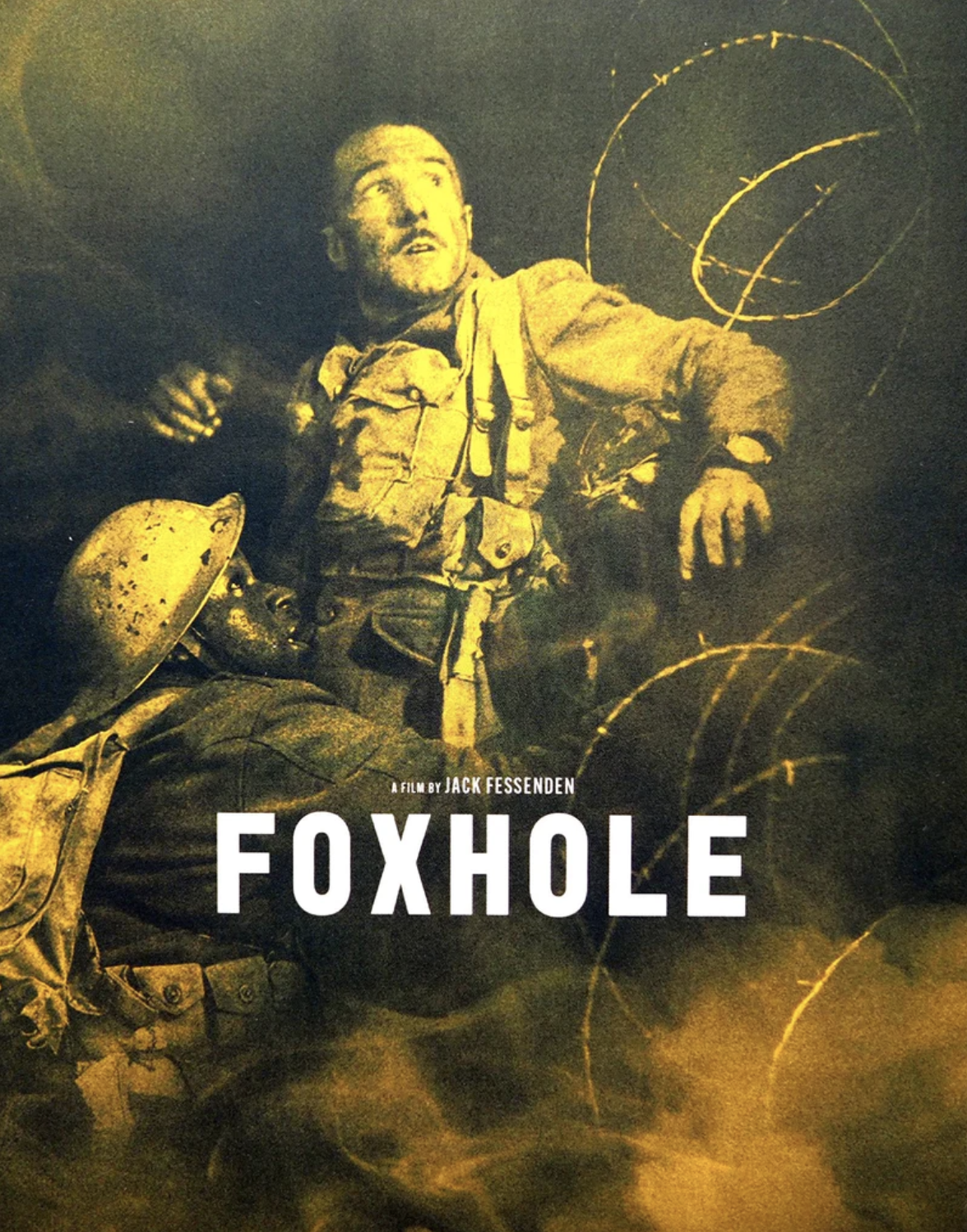

In an insider nod to horror fans, Lloyd Kaufman and Larry Fessenden make brief appearances in ill-fated encounters with Milo. The bloodletting here is a million miles away from the cartoonish schlock violence of Kaufman’s Troma brand, but not entirely unrelated to some of Fessenden’s low-budget early horror films, with their focus on human psychology and social milieu over traditional genre elements. Fessenden’s long association with Kelly Reichardt as a producer also is relevant, given the acknowledged influence here of that filmmaker’s minimalist realism.

O’Shea uses the bursts of droning ambient noise and the somber electronic sounds of Margaret Chardiet’s score to arresting effect. But he’s less interested in creating suspense or pumping up atmosphere than in exploring the ways in which horror, and its intoxicating relationship with death, can be a paradoxical balm for the more earthly cruelties of life. That makes The Transfiguration a difficult movie to classify, but one with an emotional depth that creeps up on you.

Check out the full review at HollywoodReporter.com

Add a comment