ROGEREBERT.COM—Simon Abrams | February 16, 2016

Hell to Pay: Indie Horror Icon Larry Fessenden on Wendigos and Ugly Americans

POP HORROR— 18 Aug 2018

Cult Filmmaker Larry Fessenden Talks ‘The Ranger,’ ‘Depraved’ And More – Interview

THE BEAT— 11 Oct. 2018

Larry Fessenden on Carving Up Space for Horror in a Comics Convention

ANTHEM MAGAZINE—22 Mar. 2019

A one-on-one with David Call and Larry Fessenden

AV CLUB—03 Mar. 2019

Larry Fessenden on Frankenstein, art, and Universal’s Dark Universe: “They don’t understand horror”

DAN’S PAPERS—26 Mar. 2019

Danny Peary Talks to ‘Depraved’ Director Larry Fessenden and His Four Stars

TALKHOUSE—Larry Fessenden, 09 Sept. 2019

Musings Of a Filmworker

Rue Morgue— 23 Sept. 2019

INTERVIEW: GETTING “DEPRAVED” WITH LARRY FESSENDEN

Ready Steady Cut—16 Dec. 2020

Depraved: an interview with Larry Fessenden

SCREAM HORROR MAG— 26 Dec. 2020

AN INTERVIEW WITH DEPRAVED FILMMAKER LARRY FESSENDEN

ComingSoon.Net— 18 April. 2021

Larry Fessenden on Unique Role in Horror Pic Jakob’s Wife

BLOODY DISGUSTING—27 Aug. 2021

Larry Fessenden Revisits ‘The Orphanage’ to Discuss the Remake He Never Ended Up Making

AMERICAN CINEMATOGRAPHER— 11 Jan. 2022

Halyna Hutchins: A Cinematographer’s Legacy

RUE-MORGUE— 5 Apr. 2022

EXCLUSIVE INTERVIEW: LARRY FESSENDEN ON GLASS EYE PIX’S PAST, PRESENT AND FUTURE, PART ONE.

RUE-MORGUE— 8 Apr. 2022

EXCLUSIVE INTERVIEW: LARRY FESSENDEN ON GLASS EYE PIX’S PAST,

PRESENT AND FUTURE, PART TWO

![]()

8 Apr. 2022

EXCLUSIVE INTERVIEW: LARRY FESSENDEN ON GLASS EYE PIX’S PAST, PRESENT AND FUTURE, PART TWO

Below we continue our interview with filmmaker/independent horror mogul Larry Fessenden (which began here), currently enjoying an expansive retrospective at New York City’s Museum of Modern Art. All of his directorial ventures and many more movies he’s produced through his Glass Eye Pix company are screening in this series; go here for the full schedule and details. Fessenden also works frequently as an actor, and he reveals that he recently wrapped a small role for one of the true greats…

What does Glass Eye have in the works now, especially horror-wise?

Well, as soon as I finish my MOMA retrospective, I’m going to start on my next film. It’s written, and I wanted to shoot last fall, but I couldn’t quite wrap my brain around it, and I did a couple of acting gigs. This may be a scoop for you: I’m in KILLERS OF THE FLOWER MOON, the Martin Scorsese film, which I made sure to make myself available for whenever that was going to happen. It was just a couple of days’ work, but it was very seminal for me. He’s my favorite living director, and I savored the whole thing, and spent time reviewing his movies and reminding myself how much he has meant to me over the years. That was a big deal.

Who do you play in KILLERS?

I’m in, ironically, a radio broadcast that happens in the film. It was a nice nod to [his audio-horror/drama series] TALES FROM BEYOND THE PALE, and I guess that’s all I can say about it, but it was a special experience. So a number of things kicked my film out of fall production, and let’s face it, I wasn’t ready. But now I’m eager, so that’s what I hope to be doing next. And I have a film that I produced called CRUMB CATCHER, by Chris Skotchdopole; it’s his first feature as director. We shot that last summer, and it’s in post right now.

You know, the thing is, people keep growing up and moving on from Glass Eye. Jenn Wexler [THE RANGER] is hoping to make her own film now, not a Glass Eye movie, but we’ve certainly been trying to help her for a year or two. People graduate from our fold, which I encourage, but then the new crop comes in with new projects.

What can you tell us about your next movie and CRUMB CATCHER?

CRUMB CATCHER is a thriller that stars John Speredakos, who is one of the longest-standing Glass Eye collaborators. He was in WENDIGO, and then about 12 of our other movies, and a lot of our radio plays. And then we have three other great cast members; it’s a four-hander, four people in a house, and it’s a thriller, not horror per se. [According to the IMDb, the plot concerns a newlywed couple held captive in a remote lake house by a crazed inventor and his wife.] But we don’t really think about genre; we think about the unfortunate situations that people find themselves in in our movies [laughs]. So I’m excited about that.

As for my own film, I never talk about my movies in advance, but I am very excited about it. I hope to get it out quickly, because it’s been burning for a little while now, and I’m eager to get it out there.

Your directorial projects have all had similar themes running through them, such as environmental concerns. Are we going to see those carry over into your new project?

Yes, but that’s because I’m mostly concerned with how humanity, and Americans, I suppose, put society together. This was an urgent issue 10 years ago, and now it has even more urgency, because there’s more distortion and lack of respect for truth, there’s more manipulation, there’s more narcissism and self-involvement and more environmental collapse. All the themes of horror movies are unfortunately coming true: the apocalyptic ideas of zombie movies and societal discord, and addiction themes and vampirism. All the themes that I’m interested in, I think they’ve always been true, but they seem very acute right now, as the world becomes overrun with avarice. It’s just getting louder and louder, we can’t find an escape. The theme of THE LAST WINTER is, you can never go home if the environment’s collapsing, if there’s climate change. You can’t escape anywhere, and I feel like with our technology now, and our social media, you can’t escape the noise of other people, and that’s another form of deep, deep depravity.

So the answer to your question is: Yes, those themes will always be in my movies, until humanity gets their shit together. And then I’ll be happy to make comedies. Everybody always says, “Why don’t you make comedies?” because I’m actually a very silly person [laughs]! But it’s because I’m so upset.

You mentioned zombie movies, and you’ve previously done your own variations on vampires, werewolves and the Frankenstein story. Do you have a zombie movie in you?

Oh, I do! It’s called PITILESS SUN. It’s a hard name to say, but if you see the words, it’s profound, and it’s from a famous poem [“The Second Coming” by William Butler Yeats]. I’ve been trying to make that one for years; it’s supposed to take place in Mexico, and it’s a great story. I wrote it with the same guy I wrote THE LAST WINTER with, Robert Leaver, and I sent it to a couple of companies… You know, the irony is, I love the act of creation so much that the act of following through is very hard. Like, how long do you pursue a single movie? How long do you try to get it made? And when I settled my sights on DEPRAVED, it took me nine years. So it’s not like I can make a call and they make the film; I can never get enough money, and that’s because the movies don’t make a lot of money.

So this is a big problem that I have, but the nice thing is that I produced STAKE LAND, and that’s a great apocalyptic zombie movie; of course, they’re vampires, but they live in the mind as zombies, right? So that’s why I produce, because I get to vicariously experience movies that I maybe haven’t committed my own time to, or that I don’t know how to get done, or that are better written and conceived of by Jim Mickle and Nick Damici, who did such a wonderful, passionate job with that movie. So I’m privileged to be part of their creative process, and to be an enabler and making sure they happen. I’m much better at fighting for other people than for me, because it seems effortless. If I believe in them, I will fight to the death, but if it’s me, I’m like, “Gee, shucks, maybe it’s not to be.” It’s tough.

You’ve supported so many up-and-coming filmmakers, you’ve kind of become the East Coast Roger Corman. How do you feel about your place as a mogul in the horror world?

I think the Roger Corman thing is great; I’ve also been compared to Val Lewton, which I like, because it’s a reference to a producer who had an aesthetic that affected a small group of movies. But as a kid, I didn’t love Val Lewton because there weren’t enough monsters–it was all too subtle! So I’ll probably be remembered similarly by future kids as, “Oh, those Glass Eye movies, there was never enough going on!”

But look, you know, it’s a struggle. I have a retrospective going on at the Museum of Modern Art, which appears to be amazing. But the real thing that matters is whether you can raise the money for the next movie. And that remains elusive, so to me, I’m just struggling along, and I don’t really have a place in any kind of movie history. I’ll be a footnote, but when you’re in the thick of it, what you’ve done is important, and I do feel that I’ve helped young filmmakers find their voices, and we do get movies made. Because that’s my thing: Let’s not talk about it, let’s not yearn for more money, let’s actually make the movie. And we can do it cheaply, because we’re smart, and we care, and the art is what matters.

![]()

5 Apr. 2022

Exclusive Interview: Larry Fessenden Has So Much to SEE

An archive interview from The Gingold Files.

Editor’s Note: This was originally published for FANGORIA on April 5, 2009, and we’re proud to share it as part of The Gingold Files.

New York genre stalwart Larry Fessenden has been a very busy man as of late. The writer/director of the much-praised Wendigo and The Last Winter has become a veritable East Coast Roger Corman in recent years, producing a string of low-budget genre features for the Scareflix banner of his Glass Eye Pix production company. One of them, the psychedelically tinged I Can See You, will soon have its premiere theatrical engagement in Manhattan—with a special added bonus.

I Can See You, the feature writer/directing debut of Graham Reznick (sound designer on Scareflix’s The Roost, Automatons and Trigger Man), will be playing at the new hi-def Cinema Purgatorio theater at KGB/Kraine. Cinema Purgatorio, part of a distribution concern run by Ray Privett (a veteran of NYC’s late, much-missed Two Boots Pioneer Theater), will present with the feature a new 3-D short called The Viewer, also scripted and directed by Reznick.

“Yes, Glass Eye is getting into the 3-D business; we won’t be outdone by Hollywood,” Fessenden says. While he prefers to keep The Viewer’s story details secret for now, he does add, “Let’s just say we had Brian Spears [a makeup FX creator on Scareflix’s I Sell the Dead] on the case, so obviously there are some ghoulish delights in there. But it’s typical of Graham’s work; it’s very trippy and heady, wonderful stuff.”

I Can See You itself follows three advertising guys as they trek into the woods to develop ideas for a new cleaning-product campaign, and the trip takes a scary, hallucinatory turn. “It’s one of the more concise and artful of our Scareflix,” Fessenden says. “I’ll certainly acknowledge that it may be a bit obscure to the average audience, and it’s a little bit more of a treasure that you have to carefully unfold.” Beyond its big-screen play, he’s looking forward to more people seeing See You on DVD. “It’ll be out on Amazon and also through the Cinema Purgatorio label in late May,” Fessenden reveals. “We’re very happy to be one of Ray’s debut titles, and we’re gonna continue partnering with him because Ray is a great, hard worker. He has helped us on a lot of movies, and it’s time for us to team up in public instead of him just slaving away in the dark.”

The filmmaker further reveals the extras we can expect to see on that disc: “We’ll have a lovely making-of, and a great commentary which should be enlightening, since the film is a bit of a mystery. It will be great to hear what Graham has to say, to whatever degree he reveals his intentions. The movie is so carefully crafted with so much great sound design, and editing rhythms we haven’t seen since Nicolas Roeg. It’s very provocative and quite mysterious, and even though we’re looking forward to its theatrical run and hope people will come, it’s also a movie that will work great on DVD, where you can really spend some time enjoying it.”

Also poised to greet a wider audience soon is the aforementioned I Sell the Dead, a horror/comedy about 18th-century graverobbers written and directed by Glenn McQuaid, and starring Lost’s Dominic Monaghan, Fessenden and genre favorites Ron Perlman and Angus Scrimm. “I hate to be mysterious,” Fessenden says of the movie’s distribution, “but we’re in negotiations on a couple of fronts, and we hope we’ll be able to make an announcement within a week or two. Whoever we go with, we’re hoping for a fall release in theaters—however large that release is, that’s part of our conversation—and then obviously VOD and DVD. It really is a charming film that belongs on every shelf.”

Regarding the sequel McQuaid is scripting, Fessenden adds, “I’ve read 100 pages, and it’s totally delightful. Glenn actually does want to make another film first and get something under his belt. I just want Glenn to make more movies sooner rather than later, and The Further Adventures of Grimes & Blake will hopefully be among them, but not necessarily the next thing he does.”

And then there’s The House of the Devil, Ti West’s third Scareflick after The Roost and Trigger Man, in which a babysitter (Jocelin Donahue) makes the mistake of taking a job in a home run by a diabolical couple (played by genre stalwarts Tom Noonan and Mary Woronov). The movie will have its world premiere at this month’s Tribeca Film Festival in NYC. “We’re so excited; everybody’s coming to town for the event,” Fessenden says. “It’ll be so great to finally get that out in public. We’ve all been laboring away, once again with Graham Reznick working hard on the sound.”

There’s plenty more on the Glass Eye Pix horizon too, including a deal with Dark Sky Films for a series of new fright features. “It’s a matter of days, if not hours, before that deal is inked,” Fessenden reports, “and then we’ll be making three very exciting movies in the next year. We’ll call them Scareflix; the fact that they’re being financed by an outside company is merely a relief rather than a change of approach. These are low-budget films by some of our favorite people: Jim Mickle of Mulberry Street is making Stake Land, James Felix McKenney is doing Hypothermia and we have a very interesting filmmaker making his first movie for us, and our most contained film.

“I’ve deliberately gone to a non-horror guy and invited him to sort of step into the genre,” Fessenden continues. “He’s a great, smart director I’ve known for years, and he’s gonna make a great little movie. We’ll announce that when we have it all squared away.” (The Woodstock Film Festival recently spilled the beans about his identity, though, reporting that “director Joe Maggio [Paper Covers Rock] confirms that he will in fact be shooting his next feature film in the Hudson Valley this coming May. We can’t reveal much about the still untitled project, other than the fact that it is being produced by horror maestro Larry Fessenden and Glass Eye Pix, and that it will feature a menu of culinary delights with a side order of horror.”)

And finally, there’s Satan Hates You, McKenney’s latest feature (modeled after the “Christian scare” films of old, with a cast headed by Don Wood, Christine Spencer, Scrimm, Reggie Bannister, Michael Berryman and Fessenden) and his third collaboration with the Glass Eye Pix chief after The Off Season and Automatons. “There’s not much I can say—it was for my eyes only—but I finally saw Jim’s first cut of Satan Hates You, and I’m extremely excited,” Fessenden says. “This movie is gonna be truly, unfathomably strange, and it’s wonderful. It just confirms all my belief in Jim’s voice as a filmmaker, and Angus is outstanding in it. It’s just a crazy romp filled with truly eccentric characters.”

![]()

5 Apr. 2022

EXCLUSIVE INTERVIEW: LARRY FESSENDEN ON GLASS EYE PIX’S PAST, PRESENT AND FUTURE, PART ONE.

By MICHAEL GINGOLD

For the past four decades, Larry Fessenden has been crafting some of the best, most personal and idiosyncratic movies on the independent horror scene, and has produced dozens more via his Glass Eye Pix. With a major retrospective of his and his company’s work now underway at New York City’s Museum of Modern Art, RUE MORGUE spoke to Fessenden about his history and influence in the genre, as well as his genre acting gigs and what’s coming next.

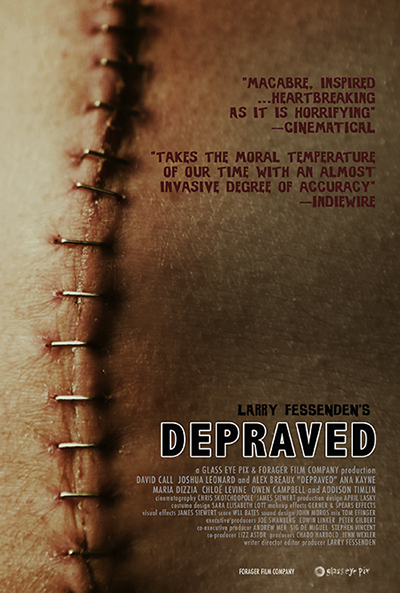

“Oh, the Humanity! The Films of Larry Fessenden and Glass Eye Pix” is showcasing both virtual and in-person screenings of Fessenden and co.’s features. The man himself is represented by the don’t-tamper-with-nature thriller NO TELLING, his semiautobiographical vampire drama HABIT, the mythological chillers WENDIGO and THE LAST WINTER, the killer-fish flick BENEATH and the FRANKENSTEIN variation DEPRAVED. Other notable movies in the lineup include his son Jack’s STRAY BULLETS and the new FOXHOLE, Ti West’s THE HOUSE OF THE DEVIL and THE INNKEEPERS, Jim Mickle’s STAKE LAND, Glenn McQuaid’s I SELL THE DEAD, Ana Asensio’s MOST BEAUTIFUL ISLAND, Joe Maggio’s BITTER FEAST, Jenn Wexler’s THE RANGER, James Felix McKenney’s AUTOMATONS, Graham Reznick’s I CAN SEE YOU and more.

With such an expansive retrospective now playing in New York, how does it feel, looking back over Glass Eye’s filmography after all these years?

I like to imagine that the tone of our movies is sort of personalized horror, and that that was unique back in the ’90s, when we started. And then I was lucky enough to meet like-minded people such as Ti West and Kelly Reichardt; she doesn’t make genre films, far from it, but there’s a sense of observation in her work, and you see that in a movie like Ti’s THE HOUSE OF THE DEVIL: the same fetishizing of detail and character motivating the stories. Obviously, HABIT is a very personal film of mine, and then WENDIGO is in a way personal as well, but I bring in mythologies and other horror tropes.

So what I like about Glass Eye is that all these movies are connected in some way, in approach and attitude. And then there’s always the aspect of craftsmanship and building a community of people who love the details in the work, like Graham Reznick, who did Ti’s early sound design in all his movies, and had great theories about that craft, and then he worked with Jim Mickle and Joe Maggio and some of the others. And Joe Maggio wasn’t a genre filmmaker either–he told personal, low-budget stories–but I loved his stuff and asked him to do a genre film. So I benefitted from meeting all these other filmmakers, and encouraging them to work at Glass Eye.

I really hate to use this word, but you were elevating genre cinema before “elevated horror” became a catchphrase. Do you see Glass Eye as ahead of the curve, and a predecessor of companies like A24?

Well, A24 of course is working with Ti West [on X], so there is a through-line. I love the recent horror films like THE BABADOOK, IT FOLLOWS, THE WITCH and HEREDITARY. Those are all remarkable recent genre films that are also dramas, and concerned with themes that are often associated with indie dramas: family deterioration, mental illness, all that sort of thing. Not that you want to become a hand-wringing sort of genre, but the reality is, that was what these movies were always about. When you see WHAT EVER HAPPENED TO BABY JANE?…that’s just a random classic, but you can go even further back, and these themes always existed in horror movies. ROSEMARY’S BABY, THE OMEN…these are films about families and struggling with darkness.

But yes, I believe Glass Eye was an early adaptive of this idea of the personal, elevated horror film, treating it not as a body-count genre–and in a way, to our detriment, not always for kicks. I mean, that’s essential to say: Not everybody likes our movies; they’re a little bit headier, they may be slow-paced, because their agenda is not simply the shocking and the gory. It’s more of a mood agenda. So they’re not for everyone, but I think it is an essential niche.

You mentioned Ti West and A24, and X, which employs a number of your past collaborators, is kind of the best Glass Eye Pix movie that Glass Eye never made. Did West ever discuss that one with you?

Oh, no, because I was never able to raise that much money. Of course, I raised money for THE HOUSE OF THE DEVIL with my fellow producers Josh Braun and Roger Kass, which is how I hooked up with Greg Newman’s company MPI, and that started a long relationship: We made THE INNKEEPERS, STAKE LAND, BITTER FEAST, LATE PHASES… But in general, I usually produce people’s early films, and then they graduate and move on, and take what they’ve learned and go off into the real world. The nice thing about Ti is that he always reaches back. He put me in his Western, IN A VALLEY OF VIOLENCE, and he always sends me scripts and we talk about whatever. And of course X was produced by Jacob Jaffke, who came up through Glass Eye, and Peter Phok, who did the same, and Graham did the sound on X. So there’s a continuity, always, and that’s what nice. Jim Mickle always picks up my calls; even recently, I asked him about an actress, and she’s in a new Glass Eye movie, someone he knew. These are relationships that were forged at the beginning, and they’ve lasted.

In recent years, you’ve been making more appearances in other directors’ movies, in larger parts. In JAKOB’S WIFE, you have the second lead, and you had a sizable role in WE ARE STILL HERE.

Yeah, well, JAKOB’S WIFE was wonderful, and that came about because I knew Travis Stevens and Barbara Crampton. We also have TALES FROM BEYOND THE PALE, the audio dramas I do with Glenn McQuaid, and that’s been a great way to meet other actors. I’ve met Vincent D’Onofrio on that; I don’t think he’s gonna call me for anything, but the point is, it’s a secret weapon to also be an actor, because you end up on bigger sets and you meet people, and it’s a thrill but it can also sometimes lead to a collaboration down the line. You know, I’ve worked with Bill Murray and Adam Driver [on THE DEAD DON’T DIE], and all kinds of stars, which is fun. But then I go back to my little camp, and they won’t take my calls [laughs].

And then I was just in BROOKLYN 45, Ted Geoghegan’s new film, which was a wonderful experience. It’s been tough with COVID, navigating through production, but we worked with protocols in place and had a great shoot this past December. I worked with Jeremy Holm, who starred in our movie THE RANGER, and I think he was cast because [director and Glass Eye vet] Jenn Wexler recommended him. So that’s nice; you see it just go on and on.

Can you say anything more about your role in BROOKLYN 45?

Just that I had very well-combed hair [laughs]. It’s a very special movie, because it was all on one set, it takes place all in one night; it sort of unfolds in real time. I think it was very personal to Ted, because he wrote it in collaboration with his dad, and it’s about themes of war and heroism. That’s interesting because my son just made a war movie called FOXHOLE, which I’ve been very involved with for a couple of years, because we shot it and then we were in COVID and it took a long time to finish. So it was funny to suddenly find myself involved in a couple of war movies, and really thinking about that sort of commitment in life, and what it takes and what bravery means, and what we’re fighting for and democracy and all that heady stuff. Ted’s movie, of course, will be great fun; there’s all kinds of ghostly things going on.

Would you ever want to star in and direct a film again, as you did in HABIT?

Oh, yeah! I’ve always threatened to remake HABIT, and I’ve lately thought that I really need to get on with it, because time is running out. You know, do people want to watch a 60-year-old traipsing around? Now, maybe I’m shortchanging audiences; obviously, there’s great movies with older leads, but that’s sort of the stumbling block. Personally, one reason I’ve stayed in the independent world is that I like having a certain amount of control, but also the interplay of all the jobs on a set. I like building the set, and I want to be in the art department, and then I want to act, so to me it’s a more personal, handcrafted medium than when you do a big film, and everything is designated. That’s a great talent as a director, to designate well, but sometimes I just want to get my hands in. So I really enjoyed making HABIT, because I was in it and I could direct from the inside, and kind of move the scene where I wanted. Subtly, of course; I was still working with the script.

You also did voiceover work on the animated horror/fantasy THE SPINE OF NIGHT.

Well, I really enjoyed meeting the two creators, the co-directors. That’s a special movie, though my stint on it was very brief, but it’s wonderful as an actor to be involved in interesting projects and meet the filmmakers, and gain the insight into how they make their movies. Everyone has an origin story; that’s the nature of movies.

Having taken part in the animation process with SPINE OF NIGHT, have you thought about Glass Eye doing animated films?

Well, my wife Beck Underwood is a stop-motion animator, so there’s always a great affection there. And actually, when I did CREEPY CHRISTMAS, a little holiday-themed, spooky film festival of 25 different artists offering their little Christmas movies, I’ve been lucky to get one of the 25, and I always do animation. I do my own stop-motion, alone; I made a short called WILD RIDE, and one called SANTA CLAWS, and I really love the process. We have a movie at MOMA called THE PAST INSIDE THE PRESENT that’s 7,000 hand-drawn pictures, really cool, almost a form of rotoscoping, which is what SPINE OF NIGHT was. And even in my own feature films, I use pixilation and animation; WENDIGO has a lot of those techniques.

So I love all the different textures that are possible in storytelling, and that’s why I love horror, since it allows for more surreal and visionary expression, because very often they’re subjective. They’re frequently about madness and the darkness, so you’re allowed to use more unusual cinema tricks that might not make sense in a normal drama, you know?

![]()

AMERICAN CINEMATOGRAPHER

11 Jan. 2022

Halyna Hutchins: A Cinematographer’s Legacy

Looking back at a life ended by an on-set tragedy, and forward with an array of veteran motion-picture professionals who discuss workplace safety and how the film community can do better.

Producer-Director

Larry Fessenden

I run a small production company out of New York called Glass Eye Pix. We have made dozens of movies, often with first-time filmmakers and often with the same crewmembers.

Our motto is: “Safety first, movie second, feelings third.” And by “feelings,” I mean ego. For me, this has philosophical weight. Safety of body and mind is the most important, and over the years the concept has expanded from car crashes and gunplay to include sex scenes, dietary restrictions and reasonable working hours. Let’s just say it up front: Good food, communication and a respectful schedule are essential to a creative team’s morale.

Having said that, production safety is everyone’s responsibility. As a producer, my approach is to build a community of trust around the movie — the thing we are working together to achieve. I want collaborators who are enthusiastic and who bring a sense of pride to the project. I encourage camaraderie as well as personal responsibility among the ranks. If it’s just another gig, they’re not going to be fully engaged in creating the kind of environment where everyone can do their best work.

At every budget level there should be a pursuit and expectation of excellence and care. On the low-budget ($250,000-$3,000,000) films I’ve produced — which have included fire, guns, underwater sequences, icebreaking, plane crashes, car crashes, boats sinking and bad weather — everyone knows each other and has each other’s back. A crew with fewer people means that everyone takes on more responsibility, and this group mentality has the effect of focusing everyone’s attention.

This also goes for those in above-the-line production, who must be responsive to the needs of the crew. If there’s a fear of speaking up on set, you’re already in trouble, and those producers who are cutting corners and pushing crews past their limits are ruining the business for everyone else. Producers must listen and assess. If a complaint is well-founded, you adjust. A filmmaker who truly understands the power of film knows you don’t need to endanger people to create a sense of danger on the screen. As Hitchcock would say: “It’s only a movie.”

Even so, I consider filmmaking a robust activity, and I expect my team members to have some grit. I grew up loving the films of Werner Herzog, Akira Kurosawa and John Huston; these movies have an aspect of controlled danger to them. You just have to create an environment of trust where your crew feels like they’re always given a choice, and where saying no doesn’t feel like a rebellion — it might just be a reality check. — As told to Iain Marcks

![]()

THE NEW YORK TIMES

30 Oct. 2021

Why the Vampire Myth Won’t Die

Joe Dante, a veteran horror director, speculated that we have so much more to be scared of today than in recent years, both politically and medically, that “it may be difficult to go back to the purely supernatural approach.” But Larry Fessenden, who starred and directed in one of the best vampire movies of the 1990s, the intimate New York indie “Habit,” sees new opportunities for horror.

“The pandemic has heightened our fear of each other, of infection and contagion, invisible droplets delivering a cataclysmic blow to our physical beings, leading in turn to an atmosphere of deep mistrust and isolation,” he wrote in an email. “And always, there will be those who don’t believe the monster even exists. I think a wave of vampire stories that captures a claustrophobic preoccupation with death and paranoia may be filling our screens next.”

![]()

INSIDE + OUT

21 Sept. 2021

Hollywood on the Hudson with Film Director, Larry Fessenden

Meira Blaustein: Hello Larry. We’re sitting here in your interesting barn, surrounded by some of your artifacts from the films that you’ve made, including this big dead fish here–what film was it from?

of your artifacts from the films that you’ve made, including this big dead fish here–what film was it from?

Larry Fessenden: “Beneath,” a much-loved picture.

Meira Blaustein: So, Larry, you’ve been making films for how long?

Larry Fessenden: Since the 70s.

Meira Blaustein: Did you ever have this aha moment, when you realized that you wanted to make movies?

Larry Fessenden: Well, the truth is that I came to movies through acting, I wanted to be an actor. I did a lot of stuff, you know, even in grammar school where I managed to make an impression by playing a dragon in the school play. I fell over the stage backward onto my head, and everybody was talking about it for a week. So that’s where I got the bug. And then, in the late 70s, like 79, I got a Super 8 camera and I started filming. I realized that the camera told the story; where you put the camera, the first shot, leading to the next shot. So, I sort of discovered how movies were made. And I became more and more interested in all the aspects, even beyond acting, that made movies. But the thing is, movies were much more mysterious about how they were made back in those days. It was much more piecemeal, and it was a great process of discovery to become a filmmaker.

Meira Blaustein: Do you remember your first film and where you made it?

Larry Fessenden: Well, the first movie I made, I would shoot Super 8 outside with friends and sort of find my way, I really loved that. I still think it’s a great way to learn filmmaking. Obviously, now you could do it on an iPhone, but to compose and to sort of edit in-camera and really think about how one shot leads to the next. My first four films: one was about a car that runs over a child. One was about a man chopping up another man in a bathtub into little pieces with an axe; that was played by my brother. And then I made an existential drama about the history of humanity. These films were all Super 8. And that’s how I found my way.

Meira Blaustein: Larry, I know that many of the films that you have been making the past few years have been shot in the Hudson Valley. Can you talk a little bit about what makes you want to shoot in the Hudson Valley? What is unique about it? Does it affect the style or the subject matter of the films because you’re shooting it in Hudson Valley instead of any other place?

Larry Fessenden: Well, I believe very strongly that one of the main characters in a movie is the setting. And I’ve shot in New York City with great affection for the colors, the streets, the energy and the sounds. But we moved up to the Hudson Valley in 1999. We’d been visiting for five or seven years before that. And once I have a love for a place, then I want to put that on film. And, all the seasons are great. I made a movie up here in the snow, and there’s so much richness. And now as I get older, I just like being at home, and sort of realizing, you know, you can shoot something just down the road. And if it’s composed, right, and it’s part of your story, it becomes really exciting to capture something that you know; the light and all the things that you’re familiar with in one place. I’ve shot in Iceland. I’ve shot in Tennessee and Mississippi. But I always tell people to shoot upstate. There’s vitality and enthusiasm here. Even though now it’s HBO and Netflix, we still make independent films up here and I believe in holding to that ideal.

Meira Blaustein: You are the epitome of independent filmmaking. You’re considered the uncrowned King of Horror Film, especially in the independence genre. Can you talk a little bit about the meaning of selling out in film?

Larry Fessenden: The whole idea of selling out. I’ve had friends over the years who were frustrated with me because they thought I should be more famous, or just famous for that matter. And you know, you can’t actively sell out. What selling out really means is getting a job in a big budget studio. And I’ve had many interviews over the years to try to make bigger pictures. I came very close to making a movie with Guillermo del Toro called The Orphanage. And it’s funny when it fell through, everyone assumed that I asserted my independence and said “to hell with Hollywood”, and walked away in a huff. But that’s not it at all, I wanted to make the film. I love the artisans, the professionalism of the Hollywood system. But the reality is, when I sit down to conceive of a project, it has an offbeat nature because I’m interested in riffing on cliches that are known in cinema, especially my genre, and then bringing something very personal in. So, there’s enough of a contradiction there that it appears to be uncommercial. I would say that I have a very long sellout in that I’ve set up what Jason Blum does. Over the years, I made the idea of personal horror films my little corner of the world, and now that’s much more popular. Even a movie like Hereditary and other artful horror movies sort of spring from that genre. So, I’m just a slow sellout.

Meira Blaustein: Thinking back about your career, be it acting, producing, directing, or nurturing young budding filmmakers, is there anything that you can take from those experiences? And think of it as one of your favorites? And if so, why?

Larry Fessenden: Well, I’m very lucky because the way I interact with the business is very varied. Sometimes I’m a very small actor in a big movie, I’ve done that. I’ve worked with Jodie Foster, Adam Driver, Bill Murray, and wonderful movie stars that I love as a fan. I’ve been in a Scorsese movie. I was in the Jim Jarmusch movie twice. These are seminal moments because you’re working with people that you like, as a consumer of cinema, so to speak. They are cherished memories, but usually, they’re fleeting. Then, on the other hand, I have my own films that I lived with, and to actually realize them on screen is so meaningful. Wendigo was a fulcrum because it was both extremely personal and it was in this very location, the Hudson Valley. I also had wonderful actors Patricia Clarkson and Jake Weber, so that’s kind of a great memory. But then there are other things that I cherish because I fought so hard to finally got it made, like my film Depraved, which is my Frankenstein movie. I went to Hollywood, and I pitched it for seven, eight years. I finally made it for very little money and now it’s on the screen, or as I say, it’s on the shelf, because I like physical media. So many, many cherished memories. I’m very lucky. I feel like I’m a journeyman more than what everyone says– that I have a successful career. I always correct them and say, “No, but I have had many wonderful experiences in the movies, the business of movie-making”.

Meira Blaustein: You’ve been part of the Woodstock Film Festival, at least since 2001. Many of your films have been at the festival, and films by your friends or people that you’ve supported have been in the festival. What do you think the role of the film festival is, for a filmmaker’s career as well as just the film industry at large?

Larry Fessenden: Film festivals are essential, especially for indie filmmakers. Very often you found the money, and you’ve made the movie and now you have to sell it. So, it’s an important business venture to go to a film festival. But more importantly, it’s where you learn whether your film is going over in front of an audience. There’s a ritual of going. You meet people and you scheme. You talk about your movie and have the actual applause and the Q&A, or the silence, and then the interrogation. But either way, you’ve just finished your movie and you finally get into a festival. I can also say, festivals bring great heartbreak because unfortunately, there’s a hierarchy as with all things in movies, and so you want to be in Sundance, and then you don’t get in. It’s just like trying to be with the popular children. It’s like everything in life. There’s this hierarchy that you’re always dealing with, so it brings sadness as well. It’s great vindication and happiness–I’ve sold some movies out of festivals.

I love the Woodstock Festival because it feels like home. And it’s fun to be in your own environment going to events and feeling a consistency because I have been through my films and films made by my friends. I always enjoy the vibe of the festival up here. But that’s also because I like being at home. I’ve traveled to exotic festivals all around the world and it’s always thrilling. You’re in a bubble of cinephiles.

Meira Blaustein: I know that you’re working on a number of projects, can you talk a little bit about what’s coming up for you?

Larry Fessenden: I don’t usually talk about my own films, because I have many superstitions. I’m writing a movie that I will shoot in upstate New York, in this beloved area. And that’s what I was talking about. I literally want to shoot on the road next to this–I don’t even have to get my car. In a funny way, it requires a great many locations in our community. I’m going to have to see if the shopkeepers will let me just quickly drop in. So that’s all in the next six to eight months that I’ll be scheming to do that. More importantly, I was the producer of my son’s film, which is called Foxhole and I’m very excited that it’s playing at the Woodstock Film Festival. It will be premiering in the US here. And I can’t wait to show it, I’m very proud of the film. It had an extended life because of COVID, so we sort of took a year, waiting around for the opportunity to show it. We filmed right in the backyard, as we like to do, and yet it’s a very ambitious and quite a beautiful film. I’m also a proud father. I produced a movie that’s still shooting in California. I help films get made in different ways. Sometimes small investments, sometimes I give them my insurance, sometimes I give them a word of encouragement and recommendations. So, there are many ways that I’m involved in movies, and I’m acting in some films as well.

![]()

BLOODY DISGUSTING

27 Aug. 2021

Larry Fessenden Revisits ‘The Orphanage’

to Discuss the Remake He Never Ended Up Making

“Well, I was in my office in downtown New York City,” Mr. Fessenden begins. “I got a call from a Hollywood agent. They asked if I wanted representation. I said, ‘Well, I don’t know why you’d want to represent me. I’m just an indie filmmaker from the East Village.’ And they said, ‘Well, no. You’re going to remake The Orphanage.’ At that point, all I knew about the project is that it had been produced by Guillermo del Toro, and it hadn’t even been released yet.

“I said, ‘That is crazy.’ I told her I’d get back to her at some point. I called my pal Ron Perlman, who had been in my film The Last Winter. ‘Ron, what do you know about this?’ Because of course, Perlman was a friend of del Toro, and Perlman was on set doing Hellboy II, I think. He said, ‘Oh, well, Guillermo has news for you.’

“So it turned out that Guillermo had very kindly handpicked me to direct the remake. And it also turns out that Guillermo had been something of a fan of my work, starting with the movie Habit. We had never met, but I came to learn that he had been a supporter behind the scenes, which I’ve appreciated ever since. So I was hired by New Line, which was on a high right then because they’d made the Lord of the Rings with Peter Jackson. They were a company that was going strong at the time.

“I got a translation of the original version of the script, and I went to a private screening of the movie. I thought it was beautiful. Lovely direction, a very elegant piece. The good thing is that I could still imagine what I would want to do with it. So I took the script, and my memories of the movie, and I actually wrote a draft before ever meeting Guillermo. I sent it to him and he said, ‘Why don’t you come to Los Angeles, and we’ll work on this?’

“When I sat down with him, he said ‘Fessenden! It’s like you’re sleeping with my woman, writing a draft before we talk!’ And I laughed. I said, ‘Well, listen, man, I just wanted to get to know the material, and I look forward to talking to you about it further.’ So we kind of started over. Not as a rejection of my work, but to have a conversation in a very organic way about the remake.

“When I sat down with him, he said ‘Fessenden! It’s like you’re sleeping with my woman, writing a draft before we talk!’ And I laughed. I said, ‘Well, listen, man, I just wanted to get to know the material, and I look forward to talking to you about it further.’ So we kind of started over. Not as a rejection of my work, but to have a conversation in a very organic way about the remake.

“It was like being in a film noir or something. I was staying in a hotel in Thousand Oaks, which is sort of a mountain suburb of LA, and then in the morning I would drive up the long road to his house. His assistant would greet me at the door, and I would go into his little playhouse. This was his second house, not where his family lived a ways away, but just where all his monsters and toys lived. It was filled with beautiful books and art and sculptures of his favorite fantasy figures and props from his own movies.

“There was a Jaws room, and a Hitchcock room, a room of illuminated manuscripts. It was just a wonderful museum. In fact, he wrote a book about that house called Cabinet of Curiosities. You can see what I’m talking about. I think it got threatened by the fires last year. I hope it’s still there. And you know what else? Just to give some context, Guillermo was packing stuff to go down under to make The Hobbit. So that was the setting. Imagine sitting there with the maestro himself, talking about the script. What I found is that he’s just got such a deep knowledge of genre, but a depth derived from literature and mythology, high-brow and low-brow, and of course from movies, too.

“So we spent about four days where we would chat and then I would go back to the hotel and write stuff, and then I would come back and we would chat some more and we built the story together. We’re almost exactly the same age. But Guillermo, with his experience, his intelligence, and his success, felt like my elder.

“It was a real education. I believe we had fun together. I mean, I certainly had fun, but I think he got a kick out of it, too. Because when you are an artist, you enjoy the work, the problem solving, and the camaraderie.

“Then I went off back home to the East Coast and wrote the script. I would get notes from him, then we’d get studio notes. He would send me e-mails in ALL CAPS saying, ‘Fessenden! What are you, Agatha Christie?! There’s so much dialogue!’ And I’d be like, ‘Fuck you, man! I got all these points that need to be made!’ [laughs] All very inappropriate, I guess.

“I finally invited him to be billed as co-writer on the script because I just felt his influence had been so essential. He brought some very personal things to the story. For example, his own father had been kidnapped in Mexico when he first became famous. Guillermo had to figure out how to negotiate with the kidnappers to get his father back safely. He brought some of this personal experience to the story. As you know, the child goes missing in the story, and Guillermo was talking about how when a tragedy like that strikes, people show up and say they’re clairvoyant, that they can help you find your missing loved one. We incorporated that very personal experience into the script. The draft we came up with was not that different from the original, but very different in nuance and temperament.”

For those who haven’t yet seen the original film penned by Sergio G. Sánchez, a brief synopsis: Decades after having been adopted as a child, Laura (Belén Rueda) returns to the shuttered orphanage where she had spent much of her youth. Accompanied by her husband Carlos (Fernando Cayo) and adopted son Simón (Roger Príncep), Laura intends to reopen the orphanage to care for disabled children. While there, her son (revealed to be HIV positive) declares that he’s made a new friend in Tomás, who he illustrates as a child wearing a creepy sack mask.

Not long after Laura discovers sinister social worker Benigna Escobedo (Montserrat Carulla) sneaking about the orphanage, Simón goes missing. A police psychologist suggests that Benigna may have abducted Simón, all as Laura and Carlos search desperately for their son. Months pass, until Laura happens across Benigna in town just before the suspected kidnapper is hit and killed by an ambulance. In the aftermath, it’s discovered that Benigna had worked at Laura’s orphanage, hiding her deformed son Tomás there until a cruel prank by the other orphans inadvertently led to his death.

With no other leads to go on, Laura enlists medium Aurora (Geraldine Chaplin) to suss out Simón’s whereabouts. Aurora holds a séance, telling Laura that she can see the ghosts of orphans from Laura’s own past, which leads our heroine to a terrible discovery: the bodies of the orphans, each having been poisoned by Benigna for their role in her son’s death.

The orphans’ ghosts guide Laura to her son, revealed to have died on the very night of his disappearance, having been trapped in a secret room beneath the orphanage. Laura overdoses on pills, freeing her spirit and taking her place as the caretaker of the orphanage’s ghostly residents, including her own son.

“The most substantial thing that I changed, that I really was passionate about, was I made it all happen in about six days,” Fessenden reveals, discussing his own take on the original material. “Whereas in the original film, it says ‘Six Months Later’ after the initial setup. When I see that in a movie, I always feel like, ‘Well, what the hell happened during those six months?’ I am quite literal that way. I just felt that I wanted to have the intensity of a mother not knowing where her child is, a child who was sick and needed to take medication. Every day, every hour would matter. I felt it was a revision to the original that would give it a different energy.

“And I wanted to make it a contemporary ghost story, set it in modern-day America. In my mind, I was going to shoot it differently than Bayona had by making it more naturalistic, with more of a Polanski vibe. I wanted to shoot in Gloucester, outside of Boston, on the shore. There would be a real, practical location with a lighthouse. We would have the orphanage there. I even traveled to Gloucester a few times because I knew the area. I had gone there and taken pictures, really getting a clear idea of how it would all go down. Guillermo and I had some differences about how it would be shot. He was more oriented to the control of working on a set. But, you know, I looked forward to the challenge of convincing him I was right.”

Was there any sort of mandate as to how faithful Fessenden had to be in adapting the original story? He explains: “Look, I like updating classic stories like Frankenstein and Dracula. And when you update them, you have to bring a psychological realism to the telling to reassert the vitality of the stories. I had slightly new perspectives about the characters’ relationships, about the agony the mother would have been going through. And about thematic things like the piano piece that the kid plays, and the details of the maps, and the clues and the games.

“One thing is, I didn’t even want the kid to be sick. I fought with New Line about it, and they won. I didn’t mind having them win, but I was like, ‘How many tragic storylines do you even need?’ You know? I didn’t need that, but it was fine.

“Guillermo was, I think, on the fence about that, and a number of my impulses. He of course had been involved in the first one. So he could see the merit of all the choices that had been made. He loved the original. I don’t think it was ever that he wanted to do it better. He just was curious to try it a different way, and I think he felt the property could afford a revisit. Anyway, we were pretty faithful all the way to the end.

“One thing that we brought out that I thought was cool was that they are reading Peter Pan in the original, and I leaned into that. You know, I delved deep into that book by J.M. Barrie, which is a book about children that don’t grow up. And of course, if all the children are dead in the orphanage, they are suspended in their youthful state. So there are lots of themes and connections that we made that amounted to a difference in emphasis. I think that’s what can make a remake interesting.

“Also, remember, another fun thing is that the third part of the movie is basically like a Ghostbusters sequence. I watched all the Ghost Hunter TV shows and had a lot of fun doing that research, just to sort of evoke all of that. Now we can say it would be similar to a movie like Insidious, but those ghostbusters are kind of played for comedy, which never suited me. So we really leaned into what that experience would be like. Maybe nobody needs to make this movie now, because it’s kind of like the Conjuring movies in terms of ghosthunters showing up and dealing with family trauma. But this was before all of that. So at the time it seemed fresh. And I wanted to make that sequence terrifying and sad.”

Fessenden giggles at this point, thrilled at going back through the beats of his story. He laughs, puts on an old-timey, Mid-Atlantic accent: “Now I’m getting excited! I’m gonna call the coast! We’re gonna make this picture!”

Fessenden notes that his screenplay retained many of the same names as the original film, though the character of Benigna Escobedo was tweaked. “This character, [now named] Belinda … we expanded the character, and we sort of analyze who that was and what that storyline was. That character was important. We tracked her from the past back to present day. So quite a bit of subtle work with stuff that was already set up, but maybe not followed through because the original director had other points of emphasis. I’m mostly just talking out of my ass because I can’t remember, I should have reread the script before doing this interview.”

The original film ends on a surprisingly dark, emotional note. Would Fessenden’s version have concluded with such a bold finale? “It’s the same. We had the so-called dark ending. I just wanted the whole movie leading up to the end to be like the clock was ticking. And then, because they did keep the sickness, every day she was like, ‘He should take his medicine today! This is another day he didn’t get his meds!’ You know what I mean? It’s just more agonizing. So by the end, you’re like, ‘Oh my God, this is too much!’ Anyway, I think it was pretty great. Guillermo was very tickled that we kept it really bleak.”

Given the project’s pedigree and the box office success of its source material, it’s genuinely surprising that this particular film never made it into production. So why is it that audiences never got to see this Orphanage? Fessenden explains: “We had a fantastic script. It was very well liked in Hollywood. People felt it was really compelling, with appropriate changes to the original. Guillermo had it in mind to hire the best actresses in Hollywood. We went to absolute top-notch A-list actresses, and most of them passed graciously.”

Fessenden even reveals that the Aurora character might have been portrayed by a legendary Oscar winner. “We talked about Meryl Streep. I mean, it’s crazy, but for a fleeting moment there were some connections being made that could have led to an offer. But showbiz is filled with such illusions.

“Of course, the actors that passed, they all said that they loved Guillermo, but some of them weren’t confident in my level of ability to protect them in such a vulnerable role. Or so I came to understand. I mean, everyone had a different excuse, and the material is very dark. But it is a horror picture, isn’t it?

“Anyway, we tried to cast for about three or four months. My favorite experience was flying over to London and meeting Kate Winslet in a little hotel. She was just really awesome. When we finished our meeting, she said she would do it and she gave me a big hug. Two weeks later, I got an email from her agent saying that she was actually not going to do it. That she had done two bleak films in a row and wanted a change. But I think it’s because Todd Haynes offered her Mildred Pierce. Ha. Anyway, Kate’s the coolest.

“But, of course it’s all very heartbreaking. That was sort of towards the end. We had been declined by some other actresses of note. Meanwhile, I met all kinds of production designers, costume designers, really top notch people. All of this was delightful and inspiring. I got great stories. One line producer we met had worked on Marathon Man, and talked about how that was shot. Another artist had done the costumes for Burnt Offerings. All kinds of random, wonderful professional from the studio system.

“But, the clock just ran out. I couldn’t land an actress of the caliber they had hoped for. And then there was my last minute missteps where I went against my original instinct right at the crucial moment. When Guillermo said, ‘Well, we’ve been through all these options, we can’t figure out who to get. Who do you actually want?’ I had someone in mind. She had been my original choice months before. But instead of naming her, I faltered. Impulsively, opportunistically, I named someone else. And that someone else declined, sinking the project.

“I try not to have regrets in life, but that’s one of them. I betrayed my original instinct. After that rejection, the team said, ‘You know what? Maybe we need a different director.’ Guillermo called, and he was so sweet. He said, ‘We’re going to get Ridley [Scott]. We’re going to get an A-list director, and they’re going to make our script. It’s going to be fantastic. But in fact, they went with Mark Pellington, who had made The Mothman Prophecies, a movie I loved.

“I thought, ‘Well, Mark isn’t quite of the stature of Ridley Scott, but fair enough.’ I was excited that he was going to take over, because I really did want to see the script made. I must tell you that Mark was so enamored with the script. He really loved it, and read it three times in one day. We would chat about it, and he was just very committed. He had his own personal connections to the loss depicted in the story. But then as time went on, it was sad to see him kind of twist in the wind as well. Three or four months later, he called me and said, ‘I’m going to make an independent film. I can’t take this Hollywood game, and waiting around.’ He got frustrated, and that’s pretty much how it ended.

“When the news got out that I was leaving the production, I remember there was a lot of commentary from the indie scene saying, ‘You know, Fessenden flips the finger at Hollywood!’ But actually, it was not true. I love the professionalism and caliber of craft in every aspect of Hollywood moviemaking.

“I mean, we can talk now about how cinema has been ruined by The Avengers and all that kind of thing, but this was years ago. Ten, fifteen years ago, they would make these mid-level movies like at $20 million, and they could be auteur-driven. Hell, New Line had given The Lord of the Rings to a maniac indie filmmaker like Peter Jackson.”

Fessenden reveals here that even though The Orphanage ultimately fell through, del Toro was still keen on collaborating with the filmmaker. “Guillermo said, ‘Let’s make another movie right away.’ Another mistake I made in my life, I offered him my Frankenstein movie, and he said, ‘I can’t read your Frankenstein script because I have one of my own. I was so stuck on making that movie that I didn’t come up with some other script for him, so that was my mistake. My lesson to the kids is – you gotta be light on your feet. I should’ve given Guillermo another property that he would have made, but maybe our time had come and gone at that point.

“He remained a friend and confidant for a time. We’ve drifted apart by now, but whenever I see him, he’s still friendly, and it all feels like yesterday. Oh, and I did make my Frankenstein movie. It’s called Depraved.”

Though it’s been nearly a decade since the project was in development, is there any chance that The Orphanage might yet see the light of a projector some day? “Well actually, I think in Hollywood anything’s possible,” Fessenden says. “It’s a great story, it’s timeless. It doesn’t need a marker to make it worthwhile. I mean, maybe Jason Blum should buy it. It’s a single location. The script exists, it’s in the archives of New Line.

“You know, Jason’s on a roll. I don’t know why I’m saying this, I’m always feeling a rivalry with Jason Blum,” he laughs. “I’m just saying the script really is very cool, it is a great role for a woman, obviously Guillermo would be attached. So there’d be some cachet. But you know, things come and go. Guillermo’s great quote that he speaks – not about this movie, but just in general – that the natural state of a film is it not getting made. And that’s true, especially if you’re an indie filmmaker. You realize how many movies that you don’t get made. You know, the cliché of having the scripts in the drawer.”

Even still, would Fessenden have any interest in revisiting the film should it be revived someday? “Sure! You know, these are your babies. I mean, I remember every shot. I could shot list the movie right now. It’s all there in the ol’ noggin. I picture a movie in my head when I’m making it, and I usually put that into the script. It doesn’t mean anybody can discern it, although I bet you could get a sense of what the intentions are. And as I say, I feel like it’s a timeless story of loss and what a mother goes through, what a couple goes through. It’s appropriately moody and nasty, and it has that lyrical element of the children’s game.”

In closing out our talk, Mr. Fessenden offers up his final thoughts on The Orphanage: “I think it’s a really good property still. And you know, the original stands the test of time. Nowadays, that’s what they love to do, is remake stuff. But you know, they wouldn’t want me to do it. That’s the bottom line. They wouldn’t. That’s the other truth about Hollywood. They’re gonna look for some young pup, or maybe a woman, and that’s fine. So it goes.”

![]() ARTS HELP

ARTS HELP

25 Jul. 2021

Climate Horror and Culture Wars: An Interview with Director Larry Fessenden

What is the scariest thing in the world to you right now?

Obviously, it’s climate change.  And another thing that’s scary is that we’ve proved, at least in America, that we no longer believe in cooperation and getting along to solve problems. We’ve spiralled into a narcissistic death spiral of tribalism and I think stems from the commercialization of capitalism leading to identity obsession.

And another thing that’s scary is that we’ve proved, at least in America, that we no longer believe in cooperation and getting along to solve problems. We’ve spiralled into a narcissistic death spiral of tribalism and I think stems from the commercialization of capitalism leading to identity obsession.

This all came from the power of commercials. After the 60s, people realized they could sell their sense of identity so you’d start to become more and more oriented with the products that you bought – they became your identity.

And I’m speaking very generally to your question because I think this is a trend in human history that has happened for the last century and has led us to an intractable ability to solve problems together and there’s no greater problem than climate change.

Before we go into that film, The Last Winter, the Wendigo (a mythical evil creature in Native American beliefs) is not something that’s very common in popular culture. Why do you feel it’s an important creature of myth?

One thing I love about the Wendigo is that it is, in fact, somewhat undefinable. It, of course, originates in the Ojibwe mythology and it was, as I understand it, designed to be a cautionary tale about overreach. Specifically, if you’re caught in the wilderness with your fellow travellers you don’t attack them and consume them.

So it’s associated with cannibalism, but I think it works also as a metaphor for manifest destiny. So I’ve used it both as an intimate cautionary tale and then with bigger implications, that’s why I like it.

Also, it’s not clear how it’s depicted because it’s mythology. Not like our Western monsters where there’s an origin book – Frankenstein’s a book – so you riff on that. Whereas because the mythology of the Wendigo is so much more unknowable and unattainable, it’s that much more rich and wonderful.

What comes first when you’re developing an idea – the monster or the story?

Well, they’re inextricably linked because the way I think of things is in terms of themes and the implications. Even in speaking of a monster, the question is what is the essence of a monster, what makes the story enduring?

Why do we care about Godzilla? Well, first, it was a response to the atomic bomb and the usual sort of cautionary tale about if we play with atoms we’re going to end up with things that are out of our control. As such, Godzilla seems to be more about nature.

The character itself even has personality quirks; sometimes he’s bad, sometimes he’s good. So, you can spend all your time deciding whether he has gills or not, but you really ultimately have to deal with the themes that the monster represents.

Once you’ve decided that you’re focusing on a particular creature with particular themes, what dictates what makes it scary? You’ve used multiple approaches with the Wendigo.

Ironically the sad part of my life is that I don’t know that my movies are very scary. [Laughs]. Which is why I’m not a very popular filmmaker. I feel there’s a sense of dread in all my films, and, in a way to me, the essence of horror is unknowable dread. A lot of the themes in my movies are about self-betrayal.

In The Last Winter, it’s a self-betrayal on a societal level. How we let our disagreements – personal disagreements – overwhelm our ability to use humankind’s great resource, which is reason and communication. To toss those aside is another self-betrayal.

And then I made a movie which was disliked for reasons I don’t fully understand called Beneath which is about a bunch of kids in a rowboat with a monster in the water. The thing is, they can work together and get to shore – it’s only like 20 feet away! But instead, they argue and come up with stupid solutions that are counter-productive and actually quite vicious.

In my mind, that’s where we are politically. Instead of trying to solve problems, we’re figuring out more and more nasty ways to combat each other. That’s why I liked that film, I’m not here to apologize for it but I’m not sure why people don’t respond to that because I think it’s as biting as anything I’ve done.

It’s not your job or horror’s job, but what insights do you feel the genre has to offer in the problems we’re facing today?

I think the most relevant answer to that question is simply that, while being in entertainment, we can discuss issues that are important. But also, I don’t sit down and say, “Let’s see, what’s the issue of the day?”

I’m not a propagandist. The fact that I am saddened by something like climate change is actually much more of a personal thing where I feel that sense of self-betrayal in the same way that it does relate to alcoholism and things that are much more personal to me but also to other people.

I always reject the idea that you can’t have a story with a message. It’s funny, you know, if you make a cop movie – cops and robbers or murder and a detective – no one is saying, “You’re making films about justice, what kind of preposterous, pompous, person are you?” No, it’s in the guise of justice that I’m telling a cool story about a gumshoe who’s solving problems.

So if I have a horror film where clearly the theme is Frankenstein’s monster was brought into the world and then abandoned by his parents [Depraved], yes, it’s a movie about parenthood – but it’s also about Frankenstein which is cool! So there’s an aesthetic aspect to genre filmmaking that’s completely about the colours, the mood, the music, etc..

The greatest emotion that I feel is this sense of awe and existential bewilderment that we’re alive and then eventually we’re not alive. That all seems crazy, that you can die slowly from cancer or quickly from an axe in the head, that all seems like great stuff to make movies about.

So the idea is that entertainment is still the agenda, but not pandering entertainment that’s designed to make money; entertainment that’s designed to draw you into an individual voice, which is what a filmmaker is. Obviously, a painter is too but a filmmaker is also a singular voice and the fact that it’s a hugely collaborative medium doesn’t take away from that.

The Last Winter is a film I can see certain people having issues with. How hard is it to get something financed that’s both horror and politically charged?

It’s impossible. I can’t do it anymore. I couldn’t do it with Depraved. I had meetings for seven years about my Frankenstein story. I mean, I could have pitched it harder, it’s not a particularly political movie, but it is about society in crisis which – I thought it was in crisis then, you can imagine what I think now. [At the moment] people don’t want to finance all of my films.

If you were smarter than me or a better showman you could go in there and emphasize other elements in the meetings. I certainly did that, I said, “My Frankenstein will be sexy,” I had a lot of ideas. But in the end, I’m talking about a war veteran with PTSD during the Iraq crisis and it’s obvious I have other things on my mind than just getting the kids into theatres. It’s also a trick with timing. I always feel that if I got Habit into Sundance back in the 90s, I would have been given a little bit more mojo and it would have altered my career.

In the end, what I always talk about in showbiz is that everything from your reviews to the distribution model is about power, not to soak your ego but to continue to do the work that matters to you.

How do you feel about how media is consumed today – in this less precious fashion?

I am extremely resistant. I’m just a product of my time. I don’t even like television series, or at least I resent them, because they demand so much of my time. I prefer the 90-minute, two-hour format. I’m not quite as fetishizing about going to theatres because I have a very big television.

I believe it’s such a lost art. I grew up in New York City and I would go to the theatres to see double bills. That’s really where I saw all the 70s movies, Little Big Man or the Hitchcock movies in the 80s. At the Thalia theatre uptown, there was Cinema 80 where I saw Citizen Kane – rear-projection. Now, the kids are watching content on their phones, and apparently, they don’t really watch movies, they’re watching TikTok.

The thing about the 90-minute movie is that it’s about empathy because you’re watching someone else’s point of view. Even if the characters don’t do what you want, you’re trying to understand, and so I believe that’s a very wholesome experience.

Whereas if you’re playing video games, you’re primarily preoccupied with what you want to do which is what you do all day long anyway. Making choices to perhaps benefit yourself. I’d be fine to have an argument with someone who would school me and correct me but when they say they’re replacing movies, I get antsy.

However, you did write a video game! How was that experience compared to screenwriting?

I did indeed. I wrote it with Graham Reznick and was invited in because I was sort of a Wendigo expert. Also, because I don’t play video games, I invited Graham to participate in writing the spec script and we got the gig.

We had the best time because we loved our bosses, Supermassive Games, and they really were committed to doing something very special and unique. And, in a way, we were tasked with writing not one but 25 movies because of all the branching.

It’s really almost like just exposing the writing experience. Because, you’re thinking, “What if Henry, goes off the scene and falls off the cliff?” Well, we have to write it. “What if Mary has an affair with Louie?” And then you have to write that too.

It’s important to understand that Graham and I did not come up with the story. We were sort of the architects of the characters and then Supermassive would say, “We want these things to happen” and we had to make it psychologically realistic. That’s why I had such a good time doing it; it was almost this Choose-Your-Own-Adventure style.

![]()

ComingSoon.Net

18 April. 2021

Larry Fessenden on Unique Role in Horror Pic Jakob’s Wife

ComingSoon.net: So Jakob’s Wife is an absolute blast of a movie. I got to check it out before South by Southwest and then at SXSW, and I just love it so much, but what about it really like drew you to the project?

Larry Fessenden: Well, I have a relationship with Barbara, we’ve done radio plays together and two movies, though I didn’t see her on the first, on You’re Next, but she’s just fantastic, and I guess we’re a little bit older than the kids out there, so there’s sort of a camaraderie of being middle-aged. I liked the script a great deal, and then I had also known Travis for some years, so it was a great combination of personalities behind the camera, and it was a great role for me to do something a little different, as a man of the cloth.

CS: I was gonna say, that was one thing I talked about a little bit with Barbara as well was that it was a very different role than what we’re used to seeing you in where you’re more rambunctious of sorts, but in this one, you’re a little more timid. You’re a man of the cloth! What was it like exploring this different personality for you?

LF: Well, I like that, you know, I am interested in philosophy and some sort of thoughtful things of how do you get along in life and how are you a good leader, so there’s some sort of aspects of the character that I related to, maybe not religion, but the idea of having responsibility in a community. Then I just think it’s funny to play an uptight, older white guy [laughs] who’s sort of oppressive to his wife, so I was able to access all of my grumpy attitude. It was fun.

CS: Would you say that you had any sort of creative challenges than going into the role?

LF: No, the way I approach acting is you try to find some empathy with the character and understand where he’s coming from, and then you just bring that to each scene. Then, of course, the director makes adjustments, and you have the other actor to play off, which was a great privilege to work with Barbara. She’s so lively, always just really jams with anything. So that combination is really a winning one.

CS: It was interesting to hear Barbara talk about how long she had been trying to get this project off the ground, so I’m curious for you what was it like working with her where she’s acting in both the producer and actor’s chair?

LF: At this level of filmmaking, you’re all working together to make the movie. It was very natural to hear her concerns as a producer, she had ideas about casting, you know, Travis had written the scripts after the other writers he had done a pass, so it was fun to watch her dealing with her fellow producer Bob Portal, Travis and then me as an actor, but also as a filmmaker. It all seemed very natural to me. I often wear many hats, and it was great to see her really flexing her muscles as a producer, and she enjoys filmmaking and the genre.

CS: Since you mentioned that you’d worn different hats as well, what was it like for you working with Travis to sort of help further flesh out your character, given that you know you’ve worked as well as both a writer and director in the past?

LF: He had a nice idea, he asked us to fill out some sort of questionnaire for our characters, and it’s one of those things where I don’t think he was trying to learn what our answers were, but gave us the opportunity to sort of think about how our characters would answer the questions. Like one of them was “Who was my favorite president?” as my character, and that was sort of cool. It was fun to just come up with an answer. It forced you to give a backstory and all kinds of other things about our relationship, what was her first boyfriend, and what was my first girlfriend and all these kind of things. So I thought that was really inventive of Travis. There were other times on set when I might sometimes suggest a way to do something, but he had a strong vision. It’s all collaboration, and, you know, the actors are in the service of the director, so I only gave advice if he seemed overwrought.

CS: You and Barbara have worked plenty of times before, but what was it like building the chemistry for your character-specific relationship before bringing it in front of the camera?

LF: Well, the cool thing is that we filmed in Mississippi, but we all went down there, and we never went home, that’s where we lived for the month. Barbara and I lived in a house together, so we sort of lived the married life. Someone would make the coffee in the morning, etc., and we hung out both before and after shooting. So that was nice. I think we both knew that not only were we enjoying each other as actors and as fellow artists, but we also were sort of logging in the time together, which gives you a more naturalistic character. We just like talking. We talked about our own marriages. It was cool. It’s very not always what happens to a lot of movies. You walk on set, and you just start working, and it’s very disorienting.

CS: I can only imagine, especially if it’s like, ‘Hey, we got to go be a married couple in five minutes.’

LF: I mean, that would be a badly-directed movie. [laughs]

CS: You’ve had plenty of movies that you’ve been a part of that have gotten into South by, but what was it like hearing that this had gotten into it and then seeing this outpour of love from the horror community upon its premiere?

LF: Well, the outpour of love was so wonderful, and it was so great to see Barbara, who did work long and hard on this movie, just getting props. It really felt like it was a culmination of her hopes and dreams for the piece because it’d been through a lot of iterations. It’s always satisfying to see that, and for myself, I was very happy to be part of it, and I enjoyed that people chuckled at my whole look in the movie, all cleaned up. You don’t realize how people think of you until you change up, and then everybody’s in shock, so that was fun. For me, it was pretty torturous because I looked like I’m 20 pounds heavier just because of those. But that’s the joy of acting. You throw away any kind of vanity and really become the character to whatever degree one is in the method. That’s the job. It’s a fun, fun job.

CS: This isn’t the first time in a horror movie either where you’ve had to get bloody, but what was it like filming some of the more gory or practical effects-heavy sequences in the film.

LF: I’m always very at home with all that ever since I was a kid, you know, I’d put bullet wounds all over myself. And real blood too. I’ve always been prone to helping myself and living on the edge [chuckles]. So it was all fun, it was cold, so some of the geysers of blood got a little icky, but it’s all part of the gig. I enjoy it. In horror, you’re shocking people in one way or another, and that’s sort of been my M.O. [laughs], make people feel uncomfortable, that’s my jam.

CS: So what was it then like for you getting to see Bonnie in the full Master wardrobe and makeup?

LF: Well, Bonnie is so cool. She’s such a big character anyway as a person. She’d show up and do a couple days and then disappear, but I think design is fantastic. It obviously references Nosferatu and Salem’s Lot, those sort of categories of vampire films, and I just think that’s such a favorite of mine, and hers is so awesome. It was great fun with that kind of iconic-looking character. It’s like welcoming back an old friend, that particular conceit, that design, that sort of rat-like face.