Larry Fessenden is among the most fiercely independent filmmakers working in the American genre cinema today—and, not coincidentally, one of its chronically undervalued. Even as his New York-based Glass Eye Pix has backed filmmakers like Ti West, Jim Mickle, and Kelly Reichardt in breaking through, Fessenden himself has continued to operate at a low-budget level, where his chillingly atmospheric features—all monster movies, to some degree—have for decades observed the philosophical struggle of people to know themselves in the face of larger socioeconomic and environmental collapse. Together, films like vampirism-as-addiction allegory “Habit” and climate-change reckoning “The Last Winter” comprise a singular, deeply personal body of work; individually, they’re all striking, emotionally resonant studies of the beast within.

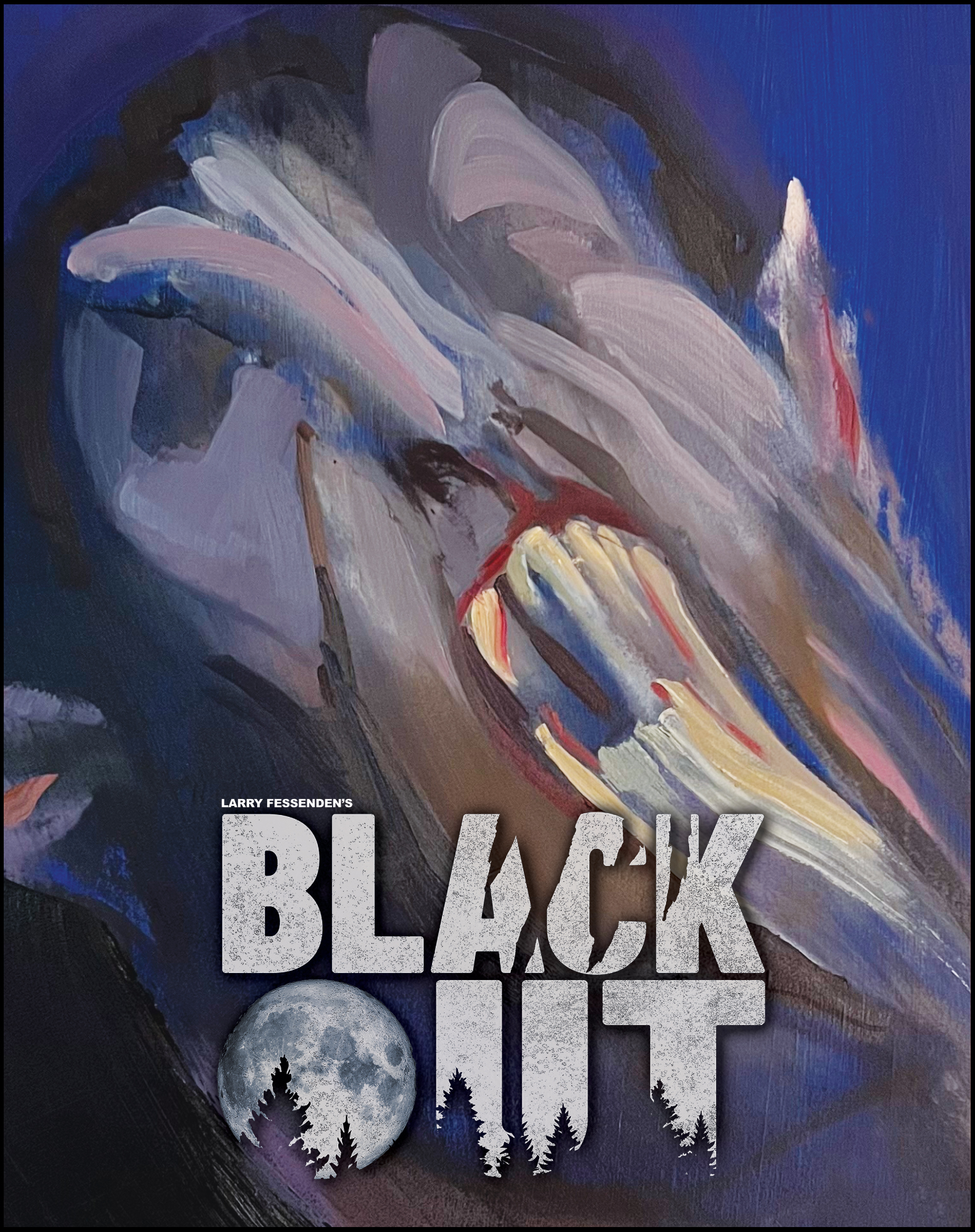

“Blackout,” released quietly to VOD this year, is perhaps Fessenden’s most haunting and poignantly hand-crafted creature feature to date—a werewolf film where an existentially afflicted outsider (Alex Hurt), having contracted the curse amid grieving his father’s death and separating from his partner, falls back into an old drinking habit and enters a downward spiral. With his liberal upstate New York community besieged by politicians who exploit voters’ fears of the Other for their own financial gain, exposing a rot in the heart of small-town America, our protagonist is caught between skipping town and standing up for what’s right — even as his efforts to suppress his animalistic instincts, and the self-loathing he’s felt all his life, make “Blackout” blurrier than a study in good and evil. That our protagonist is a painter, specializing in nature scenes that grow more violent and abstract as he transforms, gives “Blackout” an ingenious device through which to explore art as an outlet for anguish, as a mirror to the soul.

Fessenden’s long been fascinated by perversions of the psyche, and by the sorry state of a world filled with such damaged individuals; his “Blackout” is personal and political in the way of all enduring horror. – Isaac Feldberg

Add a comment