A Frankenstein for the Forever Wars

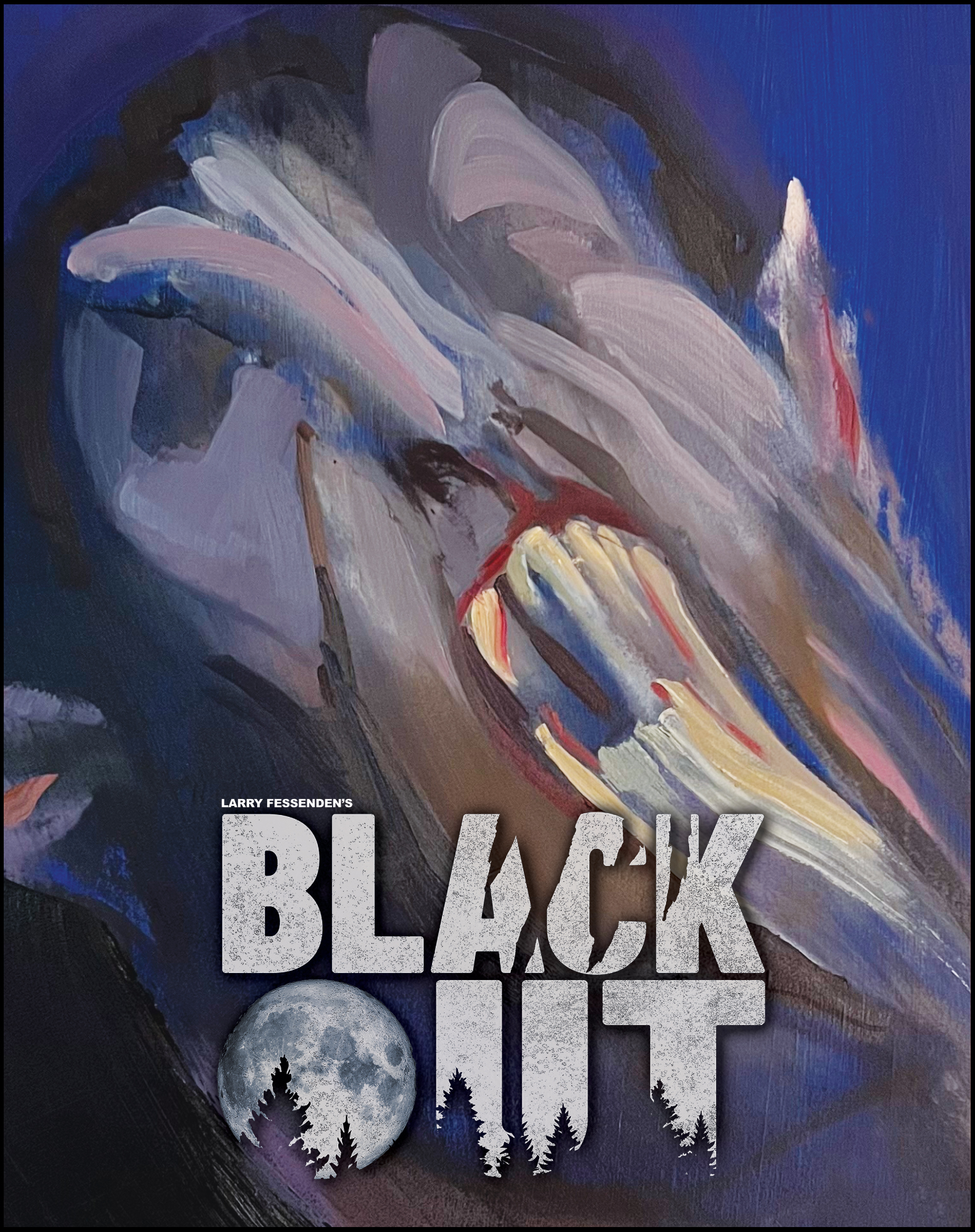

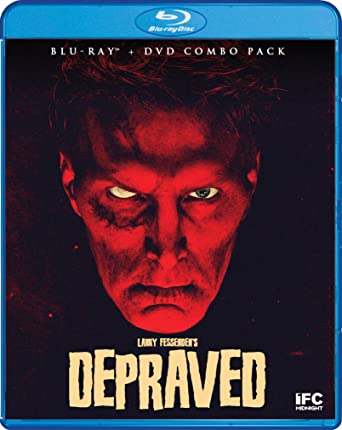

Depraved, a soulful indie take on Frankenstein, proves the perennial relevance of Mary Shelley’s monstrous creation.

Paul D’AgostinoThomas Micchelli

“Depraved” (2019), directed by Larry Fessenden, © Glass Eye Pix (all images courtesy Glass Eye Pix)

I wrote the following capsule review of Depraved, a new film by Larry Fessenden, just after viewing it, in part to spur on ideas for a fuller review:

Immediately ensnaring and narratively circuitous on levels literal, mesmerizingly visual, and metaphorical alike, Depraved is not a mashup, rather a pastiche of essentially all you might hope for it to layer, paste, stick, piece, and yes, oh yes, stitch together — from film and literary references to production values, chronologies, political critiques, and philosophies. Its enigmas run deep. Its puzzles are many. And especially with its setting in Brooklyn, it’s also a holistic embodiment of multiple forms and histories of DIY ‘life.’

But then something different took shape instead.

My colleague, Hyperallergic Weekend editor Thomas Micchelli, viewed the film as well. In a brief exchange we had right afterwards, he said that he also found Depraved compelling, and that he had some thoughts about it. So I sent him my initial thoughts in my capsule, and he then had more thoughts.

So then what we thought was this: Given that the film itself is all layers and multiplicities of disciplines, inputs, and chronologies, it could be more interesting to present a layered, multiple-voiced exchange between the two of us — a kind of review-qua-pastiche or pastiche-qua-review, not unlike the pastiche that is this film.

Below is an edited version of our exchange.

— Paul D’Agostino

Paul D’Agostino: It seems you too were flooded with thoughts after watching Depraved. Were you also flooded with thoughts as you watched it? I was, and I had so many and jotted them down so sloppily while watching, eyes wide open, in the dark, that at one point I actually turned a low light on my notes to make sure I’d be able to reread them later. I saw already that would be a challenge. Anyway, you too? And what were your initial thoughts, i.e. before I sent you the capsule? And after you read the capsule?

Thomas Micchelli: No, I never take notes. I just let my responses pile up, with the hope that the better ones will stick.

My reaction to the first frame usually presages my opinion of the entire film, and the first frame of Depraved — the overhead shot of a vinyl LP spinning on a turntable — seemed to be ushering in a movie that would be fatally arch and not terribly original.

But this was one of the rare times that the first-frame test failed, maybe because it belonged to a different movie, the five minutes of rom-com tease that you mentioned when we talked on the phone. I did think, though, that the way the overhead shot continued across the half-finished meal and ended in the voyeuristic glimpse through the bedroom doors had a refreshing earthiness to it.

We will be getting into the specifics of the movie’s pastiche of every Frankenstein imagining and then some in a little bit, but overall, the film that it evoked most strongly for me was Beasts of the Southern Wild (2012), with the first part mesmerizing and inexplicable, and the second part surrendering to the demands of plot. The first half-hour was especially persuasive — the sound design was brilliant in its ability to communicate the monster’s disorientation in his new world. The use of his point of view, including the deficiencies in his eyesight, was a device that I think could have been used more and explored further.

PD: Well, I don’t always take notes either when watching films to review, but I do at least try to jot down quotes that strike me as piquant, revealing, maybe meaningful for what might follow. Or if they’re particularly stupid. Anyway, I like your description of the first-frame test. I should try that. I do something that’s less of a test than a search for an entry into a bit of writing, again if I’m watching something I might review: I look for how much the director has attempted to pull me in, all the way into the visuals and the narrative, in the first few minutes. It’s less of a gauge of the film’s entirety than your method, but useful for me for reviews.

At any rate, Fessenden does more in those first five or so minutes than I was prepared for. But I was excited by it. It was a true jolt. As you brought up, the film opens in such completely mundane, maybe rom-com-cum-drama ways, that you’re hardly ready for what’s next. It goes from that slowish pan over some unfinished meals in a living room, into a bedroom where the couple has retreated to burn off dinner with the dessert of coitus, to a moment of happy, maybe post-coitally enlivened chatter in the living room, only to then quickly transition into an argument out of nowhere, punctuated by a claim of, “You keep setting me up to be a disappointment,” barked by Alex, whose identity won’t remain exactly that for very long.

All that’s in the first few minutes, after which a brutal murder comes almost out of nowhere, and it is extreme in its immediacy and intensity — i.e. already a different genre of film, in a sense — before then transitioning into some of the near-campy, classic sci-fi-ish, a bit flashy but also not overwrought digital overlays suggestive of electrical pulses and cerebral flashes, and so on. It’s so fast, and so suggestive already of the film’s many layers yet to come. It’s already a pastiche, and it would become much more of one — much like we already know the ‘monster’ is as a ‘thing’ pieced together into ‘life.’

Early on I began thinking of films like Memento (2000) and Primer (2004) as kindred works. Further on I thought a lot about Matthew Barney’s films and art. We can come back to some of that, but I’m interested in what you say about the monster’s eyesight. True, that did come up a lot. Similar in import, and that we can infer as elaborated throughout, was the refrain, “Gravity is your friend,” which were essentially Adam’s — at this point the monster’s name is Adam — first words, to the great astonishment of Henry, Adam’s ‘Dr. Frankenstein.’

TM: I’d like to return to your initial take on the film, its stylistic use of pastiche as a mirroring of Adam’s bodily pastiche. As opposed to a movie by Martin Scorsese or Quentin Tarantino, in which the film-geek references are subsumed into the cinematic flow, a pastiche lets its edges show, like the scars on Adam’s body. The citations pull you out of the moment and divert your attention to themselves.

The references in Depraved seem out of the blue, such as the twisting camera angle when Adam breaks loose and roams the streets, which brought to mind The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (1921), or the close-up of Polidori’s mouth eating a piece of steak, a reference that’s eluding me but I know I’ve seen. (Caligari, which revolves around a carnival barker and an unnaturally tall somnambulist, seems as much of a touchstone as James Whale’s or Kenneth Branagh’s Frankenstein films, especially given the number of times Henry tells Adam how important it is for him to sleep.)

There were a number of narrative holes, some that bothered me (there was no setup for Adam’s discovery of his backstory, making it feel rushed and contrived), and others that I found fascinating, such as why Adam has been created out of multiple parts in the first place. If the idea, as we find out later, was to find a way to bring the freshly killed back to life, there seems to have been no need for Henry to sew together an Übermensch, other than to satisfy the director’s desire to make a 21st-century Frankenstein movie. And in that light, the monster’s pastiche of dead parts seems like a critique of the enterprise.

Still, I wonder why we are talking about this movie in particular. What makes it compelling enough to single out for discussion? I can’t quite articulate it.

PD: Great point. Great points. On the latter one, I suppose we’re discussing it because it offers itself as the direct product of the piecing together, rather than blending, of genres, styles, references, and angles of social critique. It’s true that we could just leave it at: ‘Hey folks, this movie is really good, even fun, and it’ll make you think!’

But then, yes, so do many other films out there to see. But it does make sense, given its internal multiplicity of points of view, its interdisciplinarity, to address the qualities of Depraved from multiple points of view. The film festival presenting it [WHAT THE FEST!? at the IFC Center in Manhattan] seems like it could feature a number of other pictures that have similar efficacy.

I can say that it was that latter aspect that initially got me intrigued. Fessender brings quite a mix of experience in filmmaking to the table and has worked alongside many of the greats in indy film, so I was curious to see how an art-horror director whose work is shown at MoMA, and who has worked on projects with Steve Buscemi, Jim Jarmusch and Guillermo Del Toro, to name a few, might handle Mary Shelley’s classic text.

There’s also of course a very circumstantial aspect to my interest: I happened to see It’s Alive, the Frankenstein exhibition at the Morgan late last year, and it was exhilarating in so many ways. I could go on, or probably we could both go on for a while about how great it was, but that’s a different review. For now it’s worth noting that I particularly enjoyed the ways the exhibit conveyed the interdisciplinarity of Shelley’s brilliance, and the prodigious wealth of creative enterprise and expression her story has continued to generate.

Moreover, one part of It’s Alive! that I found hardest to budge from, in addition to that jaw-dropping suite of paintings by Henry Fuseli, including “The Nightmare” (1781) and “Three Witches” (1783) — and it seems that Fuseli and Shelley’s mother, Mary Wollstonecraft, according to the exhibition notes, had some manner of amorous rapport (what a detail!) — was the section detailing the impact of Shelley’s novel on the history of cinema.

Frankenstein; or, The Modern Prometheus is a story that can seem destined to be envisioned and reimagined in so many ways, through so many mediums and genres. In itself it’s everything from allegory to Bildungsroman to gothic horror delving into sci-fi, and so much more.

So those are just some of the things that got me intrigued in this movie in the first place, which then got me watching those first five minutes that had me all-in, electrifyingly so. For certain, one thing that’s worth noting before turning to your Übermensch point is that Depraved had me constantly marveling at Shelley’s prescience in telling her story. By way of one of the most effective and broadly transmittable media of her time, she told a kind of pastiche of a tale that could be enjoyed just as well at any single level of its narrative or critique, or at all of them at once, and remain just as cogent, just as potent. To watch Depraved is also to be consistently reminded of the monstrous critical importance of Shelley’s creation.

This brings me right to your point about the Übermensch, and maybe also about the critique of the enterprise: PTSD and the wars of the day are regularly dropped into all kinds of films and streaming series these days, not often necessarily or effectively, other than as constant reminders of just how long certain wars, particularly US-led or ‘fed’ campaigns, have gone on.

Here, the references to the wars become relevant to the story in ways that make sense — from the variably stilted, jarred, dazed cognitive states displayed by the film’s protagonists and graphic effects alike, to the intuitable critique of the military-industrial complex, so interested in the successful creation of this monster.

TM: When Henry says to Adam, “I want you to be safe,” he’s trying to make amends for those on the battlefield he couldn’t save, but he had to deal in death to do it.

PD: Yes, he’s working through his own mental trauma. Meanwhile, instigator Polidori seems to simply regard it all as a game, another puzzle for Henry to give Adam to solve in some kind of venture-capitalist-funded experiment in “extreme sports biology,” a telling claim.

Also telling is that moments after Henry says to Adam, “I want you to be safe,” we see him tucking Adam into bed by covering him in a blanket that looks a lot like a quilt, which at that early point in the film is also what Adam’s body already looks like — a stitched-together quilt of flesh, limbs, materials, memories, traumas.

On that note, I think we’ve covered things well enough. Let’s put this critical monster to bed, and maybe awaken it some other time for some other film or whatever else.

In the meantime, let’s test our prescience. Brooklyn DIY trend of the future, ‘artisanal A.I.’? I can see it already: “How to Make Your Own Person at Home in Seven Easy Steps.”

And forget the references to the doctor. The conceptual origin and possible prototype should just be called ‘Mary’s Monster.’

Add a comment