“Fessenden’s best, most freighted work since Wendigo.”

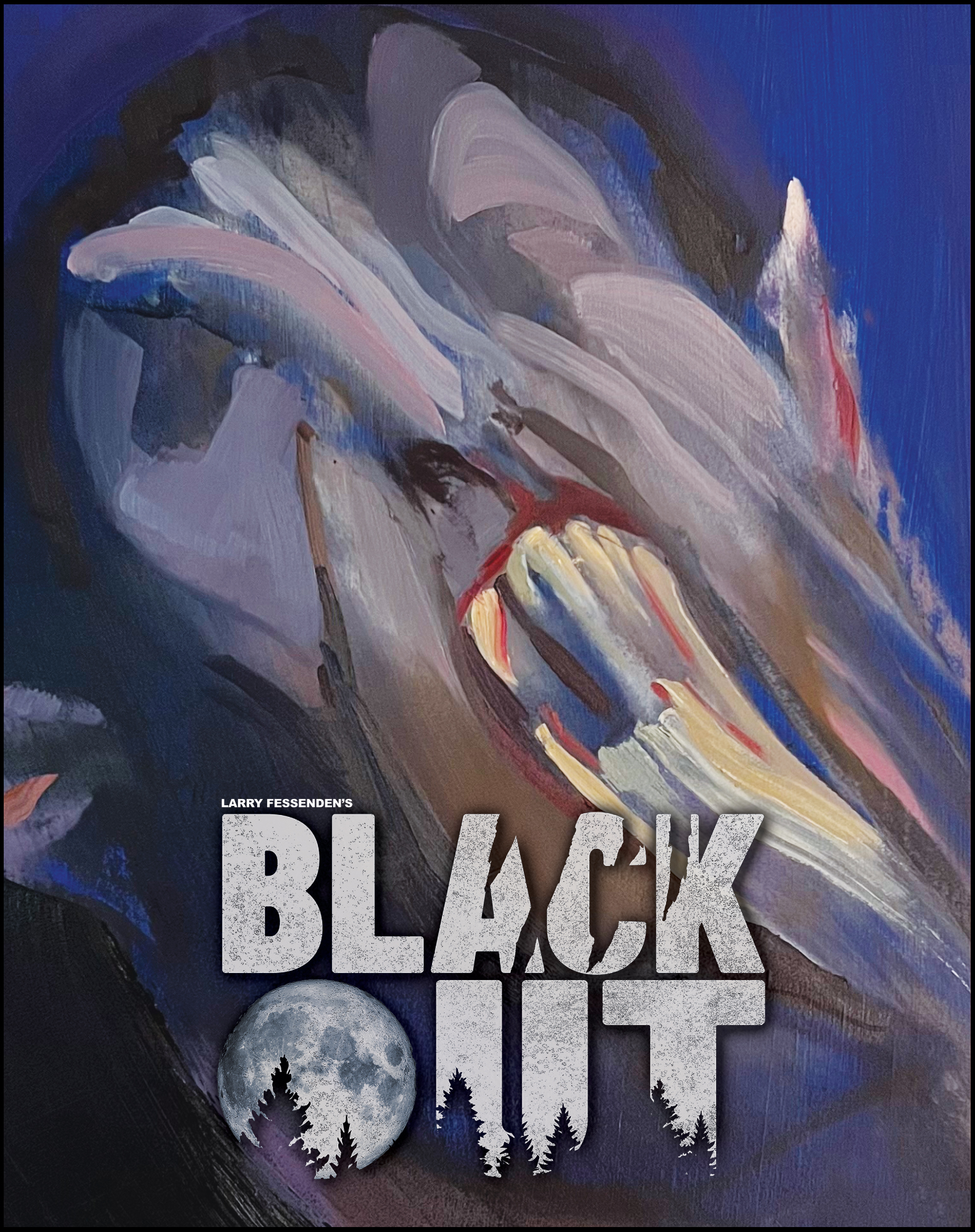

Blackout is a werewolf film in which the werewolf, Charley (Alex Hurt), “loses control” now and again, as he calls it, blacking out for a bit only to wake up bruised, bloody, and naked, covered in bits and pieces that are not his own. He has dreams of flight, and of violence, and rather than deal with his malady in a substantive way, he drifts from place to place, avoiding attachments–though because he’s charming and good-looking, attachments tend to find him anyway. I like the in-jokiness of the film’s pivotal location, “Talbot Falls” (Larry Talbot being the name of Lon Chaney’s Wolf Man), and I love how Fessenden structures his movie as a series of doomed-feeling conversations between friends, family, and old lovers helpless to save one another from the demons afflicting them. It’s the best film about mourning a person you love before they’re dead since Rob Zombie’s extraordinary Lords of Salem.

Hurt has a bit of father William Hurt’s eccentricity. He’s gangly, unconventional-looking, a little off in his delivery; watch him in a conversation with spooked local Miguel (Rigo Garay), who tells him that he’s seen a wolf man running around, murdering naked women in gorgeous Bernie Wrightson tableaux-by-headlight, and been reassured it’s just “Mexican superstition.” But, Miguel protests, the wolf man is a white man’s myth, not a Mexican one. Charley knows he’s talking about him, so he smiles a bit too wide and, in an unnerving editorial flourish, holds it for a beat too long. Charley is a complex, ambivalent antihero, horrified by what he becomes–an alter ego he tries to suppress with alcohol–but also amused by the fear he causes and more than a little drunk on his power over the small community that has rejected him and is now falling into insolvency before the economic catastrophes ravaging the connective tissues of the United States. Blackout is a laconic nightmare fueled by the madness of our social unknitting. It’s Fessenden’s best, most freighted work since Wendigo. We’re all wolves, we’re all Little Red Riding Hoods, and there aren’t any more trails through the woods. It’s all woods–and it’s dark as fuck out there.

3.5 / 4 stars

by Walter Chaw at Film Freak Central. Reviewed with Vincent Must Die

Add a comment