Noel Murray of A.V. Club took a detailed look at THE LARRY FESSENDEN COLLECTION, out now on Blu-Ray from Shout! Factory.

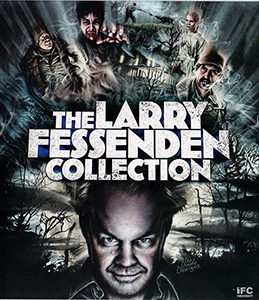

Digital media has its advantages—portability and durability chief among them—but there’s still no substitute for a good, extras-packed DVD or Blu-ray box set when it comes to putting important work into a larger context. The Scream! Factory/IFC Midnight/Glass Eye Pix co-production The Larry Fessenden Collection contains nice-looking transfers of four feature films by the New York art-horror impresario: 1991’s anti-vivisectionist Frankenstein riff No Telling; 1995’s vampire/addiction drama Habit; 2001’s man-vs.-nature monster movie Wendigo; and 2006’s global-warming eco-thriller The Last Winter. But just as important are the collection’s commentary tracks, interviews, behind-the-scenes footage, and samples of Fessenden short films and documentaries dating back to the late 1970s. There’s no easy way for a download or streaming video—or even a repertory retrospective—to replicate the archival quality of The Larry Fessenden Collection. It’s the ephemera gathered in this set that makes such a strong case for a filmmaker who’s often overlooked.

For that subset of cinephiles who aren’t horror aficionados, Fessenden is probably best-known for Habit and Wendigo, two films that walk a narrow line between fantasy and naturalistic drama—and that won acclaim from mainstream critics.Habit is the more original work, even though it came out in the mid-’90s amid a glut of similarly allusive and edgy vampire pictures. Fessenden himself stars as Sam, an alcoholic New York artist and restaurant manager who’s dealing with a recent break-up and the death of his successful father when he meets Anna (Meredith Snaider), a mysterious, sexually aggressive woman who unnerves his friends. As their sex gets kinkier and his health declines, Sam begins to share his suspicions within his social circle that he’s dating some kind of supernatural soul-sucker. But because he’s such a dodgy fellow, no one heeds his cries for help. Based on a video project Fessenden made at NYU’s film school—the short version of which is included in the box set—Habit calls back to the improvisational rawness of New York filmmakers like John Cassavetes and Martin Scorsese for a film that’s more an atmospheric, finely observed character sketch than a shocker.

Wendigo is more overtly a monster movie, playing up the ominous portents when a well-off Manhattan family travels upstate to clear their heads in a country house—where they deal with disgruntled hicks and rumors of ancient spirits in the woods. Fessenden had a little more money to work with in Wendigo, as well as a more professional cast, with Jake Weber playing cynical commercial photographer George, Patricia Clarkson playing his wife Kim, and Malcolm In The Middle’s Erik Per Sullivan as their young son Miles. But while the last third of his film becomes ostensibly one long chase through the snowy wilderness, involving a towering, antlered man-beast, Fessenden again seems more interested in what his characters are going through when they’re not living in fear of gun-toting hunters or were-deer. Specifically, Wendigo is about George’s worries that he’s a sellout, and his anxiety over whether he’s providing Miles with a strong enough male role model. In some horror films, those kind of personality details feel tacked-on. In Habit andWendigo, sometimes it’s the horror that seems superfluous.

The two features that flank Habit and Wendigo in The Larry Fessenden Collectionshare some of their strengths—but more of their weaknesses. The Last Winter has an even more polished look than Wendigo, and a higher-profile cast. Ron Perlman, Connie Britton, James Le Gros, Kevin Corrigan, and Zach Gilford play a rugged band of oil-company employees and environmentalists who have differing opinions on drilling in the arctic. But Fessenden’s usual strategy of exploring everyday lives and personal melodramas while minimizing the paranormal (represented here by vengeful, mostly unseen nature-spirits) comes out flatter and more diffused with the larger ensemble. No Telling is stronger because it’s more focused, following a married painter who comes to realize that her relationship is stuck on autopilot—and that her husband may be a secret animal-torturing maniac. Again, Fessenden is more interested in the first half of that revelation than the second, although this time he waits a little too long to shift gears fully from domestic strife to terror. In the meantime, he deftly examines how easy it is for the socially and financially comfortable to become complacent, presuming their lives of privilege haven’t come at anyone’s expense.

Fessenden doesn’t have much of a unifying visual style. His shots are well-composed, and he achieves some expressionistic effects wth camera moves (seen most memorably in No Telling’s rapidly retreating camera) and editing (as inWendigo’s periodic flurry of jump-cuts). But Fessenden uses the little flourishes sparingly. Instead, what carries over in his work is a keen understanding of what preoccupies and often divides people—be it disagreements over public policy or a creeping sense of distrust.

Because Fessenden has only made five features in the past 25 years (the fifth being 2013’s disappointing Beneath), it’s been hard at times to pinpoint exactly what makes him special. The box set helps, because in addition to extensive comments from the man himself, The Larry Fessenden Collection covers a lot of what he’s been doing between the bigger films: making shorts and music videos, serving as a producer for his friends’ horror and art-cinema fare, and working as a character actor. All those other pieces come together here into collage-like picture of Fessenden, showing him as an industrious DIY type, biding his time and staying on the margins so that he can create work of uncompromised personal vision.

In one of the interviews here, Fessenden talks about how the independent film market has changed over the last quarter-century, and how the support of genre fans—a crowd still willing to pay to own movies—kept his company Glass Eye Pix going when the festival and arthouse circuits rejected its output as too esoteric for thrill-seekers and too pulpy for serious adults. The collector’s mentality of those horror connoisseurs is partially responsible for this set. The rest of the credit goes to Fessenden, who’s been quietly assembling an impressive legacy, and now has a handy container to hold it.

Add a comment