Slamdance TV

2016

Slamdance TV interviews director James Siewert about his short film, “The Past Inside The Present” which premiered in the Animation Program at the 2016 Slamdance film festival.

Top

AXS

Justin Stokes 3/24/2016

AXS chats with filmmaker James Siewert about ‘The Past In The Present’ short

Glass Eye Pix is doing some pretty cool things. Following up on our chat with the ever-terrifying Larry Fessenden and his legion of creepy projects that’s sure to tingle the senses, we reached out to James Siewert – GEP collaborator and up and comer in the world of film that you’ll want to remember. His “cyberpunk allegory” short film “The Past Inside The Present” is currently touring the film festival circuit, bringing a pretty big discussion about mass media and the dating game.

Our interview with Siewert is below.

AXS: According to the Glass Eye Pix website, this project was announced on August 9, 2013. Let’s talk about the development of the idea, from page to screen. How did it evolve, and what turning points marked its evolution?

James Siewert: The project was something I started thinking about around my senior year of high school. The initial idea was just to do something with these heads that had circuit boards cut into the top of them. From where I’m standing now the first concept seems somewhat juvenile: the whole point was going to be that sexual satisfaction was as chemically simple as any other physical addiction – the characters would plug into each other “get their fix” and then…I’m not sure how it was supposed to resolve. It was mostly just going to be a mood piece – like if you took the basic mood and energy of Chris Cunningham’s “Come to Daddy” video and put that in the context of the robots from his “All Is Full of Love” video – I think I was hoping it would be something like that. I was very obsessed with Chris Cunningham in high school.

Early on in college it became more of a story – about this sort of traditional date night that had this weird surreal ritual built into it. I think there were a lot more bells and whistles – things that the characters did on the date – there was maybe even a thought of a single piece of dialogue or something. I was still so far away from being able to do the special effects for the thing I had in mind, so it just kind of sat there as a concept through most of college. Eventually I was doing another project where I was tracing over photographs and re-scanning the drawings, and it slowly occurred to me that this was a way to approach the cyborg short film that had been gestating in my mind for a few years. So I did some tests, and was pleased with the hypnotic dream-like effects I was getting thought the technique and thought it would take the film in the right direction.

AXS: Impressively, you were able to catch the gaze of the folks at Glass Eye Pix, who took an interest in your short film project. How were you able to do that?

JS: Way back in sophomore year of college my professor Kelly Reichardt (director of “Wendy and Lucy,” “Meek’s Cutoff,” “Night Moves,” etc.) introduced me to Larry Fessenden as someone who had the same kind of DIY spirit. He had a friend that wanted a music video done for him, and so me and Chris Skotchdopole teamed up and armed with the enormous budget of $1000, we went and made this video about a couple who is evicted from their apartment and so sets up a whole life on the street. I made one more music video at Glass Eye, so I guess I had proved myself by the time I presented Larry and Chris with the idea of “The Past Inside the Present.”

AXS: With the language of film, what were you wanting to accomplish with the cinematography?

JS: In each of my films there is a camera movement other formal element that I hope induces the psychological phenomenon that the film is really about. In this film it is the rotating camera: it was part of my initial conception that in all of the climactic parts of the film the camera would be spinning around a fixed point. The hope is that that this accelerating rotation puts the audience in a kind of hypnosis or trance – which I think people also get into during sex. I guess the idea is that the camera imitates the momentum and pace of sex – speeding up, but also having an inherently cyclical nature. The camera speeds up to the point of total abstraction and oblivion, and then dives down and through, which to me imitates the orgasm. The idea of a rotating or cycling camera is also important in terms of the overall story of course.

AXS: Outside of the expectant complimentary answers, how would you describe Larry? What were they able to supply your production to keep things running smoothly?

JS: I guess what surprises me about Larry is how classical and clear his film-making brain is – if what you’ve seen is Habit it seems like a pretty bonkers movie with a wild color palette, but actually Larry will tell you within a few seconds of meeting him that his favorite director is Hitchcock, and its clear its because Hitchcock married his artistic ambitions with a workman’s ability to break down a scene into simple pieces of coverage which are instantly legible to any audience.

AXS: What attracted you to actors Miles Joris-Peyrafitte and Schuyler Helford for this project?

JS: To be absolutely honest this was my thesis project for school – it was mostly about finding anyone who would be willing to get naked for my weird film. The thing is that I wanted people who could appear to be “generic” stand its for any couple – almost like store front mannequins – they don’t make ugly mannequins so reality is I cast good looking people. I do want to quickly acknowledge that this whole idea that “generic” really means “good looking heterosexual white people” is rightly being interrogated in culture these days, and while I don’t think my film endorses this definition of “generic” it definitely makes aesthetic use of it.

Schuyler I had been talking to about the project for years. I took a face cast of her for an initial attempt at the project which didn’t go anywhere, and took off a some of her hair off in the process. She was gracious enough to still be interested in the project after that. Miles was someone who I worked with on a few short films and then my second music video at Glass Eye. I DP’d his thesis film in exchange for his appearance in mine. He had worked with Schuyler on a play the spring before we shot this, and so the fact that they knew each other I thought was a big help in terms of not feeling too uncomfortable with the whole thing.

AXS: You used a rotoscoping technique that took over two years of animating each frame? What can you share about the painstaking effort?

JS: I mean just like anything that takes that long eventually you are doing it and you no longer really know why. One can’t expect to be passionate about anything for so long, its more just a matter of getting up and putting 8 to 10 hours in a day no matter how you feel. The nice thing about rotoscoping though is your emotions don’t really matter at all – I would just put on audio books and do it all day whether I was feeling melancholy or not.

AXS: Isolation also seems to be a theme within the narrative, but is that a fair assessment? And, does isolation necessitate the video obsession?

JS: Look at Tinder or other online dating sites – it does feel like the images we have of people and lives we imagine them leading based on those images, actually get in the way of understanding them as people. Or maybe its this feeling of unlimited access that makes every individual feel disposable in and of themselves. But I do think that the images of our lives that we create can form a barrier, and I think mostly its intentional: we want the pleasing image to block the view of the fragile person behind it, because fragile people are frightening to see – both in others and in ourselves. But of course hiding the aspect of ourselves that is fragile, ugly or frightened makes us feel more isolated than ever because those are the parts of ourselves that we really want other people to see and accept.

AXS: What does the immediate future hold for you?

JS: Well my bread and butter these days is cinematography and effects work, so I have to do a fair amount of that to stay afloat. I’m collaborating with Chris [Skotchdopole] on an idea that involves a teenage girl witnessing her father have a very weird affair with his former student. It will involve a lot the same vibes of sexual anxiety and body transformation, but maybe in a more traditionally narrative context?

“The Past Inside The Present” is currently playing the independent film festival circuit.

Top | Link

Neon Dystopia

Isaac L. Wheeler 12/1/2016

The Past Inside the Present – Surreal Cyberpunk About Identity

The Past Inside the Present is twelve minutes of intense Phillip K. Dick-esque imagery. The first time I watched the film, I wasn’t prepared for the unabashed surreality of it. Upon subsequent viewings, however, PITP evokes feelings of loneliness, withdrawal, and depression along with a kind of disconnectedness. Like many surreal films, PITP is not meant to be taken literally, and if you take it at face value it is simply confusing. It is an absurd film that has strong metaphorical context, and once you tap into the film’s absurdity, you find it’s strengths. It is really a film about identity, and how we lose ourselves.

The film follows a couple, with no affectation, who meet in the woman’s apartment. They sit, watch the news, and enjoy some wine together. Then the two of them engage in some practiced, seemingly unenthusiastic sex under the surveillance of a video camera. A shelf of dated betamax tapes suggests that this rendezvous is a daily occurrence. Then the man dresses and leaves. Following his exit from the apartment, the woman sits back on the couch and watches a videotape of herself watching television.

This is a short, seemingly unremarkable series of events, but it is the surreal imagery that surrounds our characters that really draws the viewer in and exposes the closed off emotions of the characters who seem to struggle with expressing themselves. Perhaps that alone is a commentary on our restrained society.

“Moving somewhere where I knew no one created a strong desire for a tangible link to my past. We all undergo these ordinary sorts of transformations several times throughout our life, and though we hope to persist in spite of change, I think most people experience anxiety that fundamental parts of themselves are slipping away. In retrospect it was in this environment that the plot of the film started to take shape: two characters who attempted to record and replay their experiences with diminishing returns. Other surreal images began to emerge – the fluid dripping upward and the pieces of the characters dissolving – which started to take on personal significance for me as I felt my old identity giving way to a new one.” – The Making of The Past Inside the Present by James Siewert

Viewing the film in the context of this quote we see that the characters are shells of their former selves and that through attempting to recapture their old selves, they are losing who they are. They fail to accept themselves as they are now, and thus squander whatever life may be possible for this new version of themselves. This is an condemnation of living in the past and the repercussions of doing this too long. As Siewert points out though, we all do this from time to time. We like to think of ourselves as static beings, but in reality we are a spectrum of selves that exists across a spectrum of time. When we fail to realize this, we get caught looking into the abyss of our past unable to obtain what once gave our lives meaning, just as the characters do in the bedroom scene as they are drawn apart from each other. Fascinating stuff to reflect on.

This kind of melancholy is captured well in the film’s soundtrack:

I met Geoff Saba through a music video I had directed in the spring of 2015, as a kind of distraction from the film – He had been the producer on the track. His own music was a mixture of vocal drones and electronic sounds that were hypnotic and surreal. It was the first thing I had listened to that captured the feeling I was after: the sensation of sinking – something trance-inducing that would pull an audience beneath the surface of their conscious experience. – The Making of The Past Inside the Present by James Siewert

I think this sense of sinking that Siewert describes is accurate to how I felt watching the film unfold for the first time. Metaphorically speaking, this sinking is also representative of the loss of identity explored in the film. When we don’t know who we are, who we want to be, or where we are going in life we get caught in this kind of existential quicksand, that draws us under. Siewert certainly captures this sensation in the film.

The Past Inside the Present is a twelve minute film that took more than two years of nearly continuous work to complete, so you could describe it as a passion project for Siewert. Indie Street, a film co-op model/group distribution platform, has made the film available to the public through free download via torrent. You can just download the film, or you can download the film and a bunch of extras that discuss and show how the film was made. My first interaction with Indie Street was the hilarious short film Blinky, which is a dark, funny, and awesome cyberpunk short film. The Past Inside the Present is absurd. It is surreal. Phillip K. Dick would be proud. I, for one, highly recommend it.

The Past Inside the Present – 8/10

Top | Link

Directors Notes

MarBelle 11/23/2016

The Past Inside the Present

What is it about the past which compels us to expend quintillions of bytes of data trying to preserve the minutia of our daily existences? Perhaps it’s the unknowable nature of the future, coupled with disappointments about our present, which causes us to reach for the rose tinted memories of what has gone before. This is a question addressed by James Siewert in his multi-year labour of love allegorical short The Past Inside the Present – in which a couple directly plug into recorded memories of happier times in an attempt to renew their dying relationship. Take a look at the trailer below (or download the full Bittorent bundle) and then check out our interview with James where we discuss The Past Inside the Present’s epic two and half year production journey and consider the narrative and craft casualties caused by the continuous hunt for ever efficient production practices.

The Past Inside the Present is far from typical in both its concept and execution, where did the idea come from for this labour intensive short?

The ideas for the film came together slowly and from many different sources. The very first idea, which I had at the end of high school was just to do something with these half-headed figures with analogue circuit boards on their heads. It was a much more aggressive idea in tone than what the final film became – the rhythm and vibe would have been more like Aphex Twin’s Come to Daddy video. I think it was born out of anger – feeling resentful of people that were able to have sex easily, and wanting their relationships to be shown to be superficial or at least purely chemical in nature.

Once I got to college I became much more nostalgic – because I was doing the thing where you would go home to your high school friends and play at repeating all the old jokes and routines with diminishing returns. Visiting home occasionally you get this crystallized view of how time breaks everything down because each time you go home it’s this little time capsule of what your relationships are like so you have these distinct intervals where you can clearly track how quickly feelings fade and things fall apart. So the the idea of the figures plugging into these tapes that would allow old rituals to be iteratively reenacted got incorporated into the original idea.

The last piece was how to treat the visual effects – which ended up being done with rotoscoped animation. This came about because in college I took a lot of printmaking classes. I took a photogravure class where you learned how to etch a digital image onto a copper plate. I would experiment with etching illustration back into the photographic image. I began to want to use that style in animation – I liked how the drawing allowed me to editorialize on the image that was underneath it. And I also felt that the sort of labored look you get with animation – where images seem to ‘hang in the air’ for a second – time seems to have more weight in animation – a second of animation feels more pregnant than a second of live action film. The weight of time was so much part of the concept that it seemed like the right way to treat this story. Plus it allowed me to not have to be so fussy with the visual effects – since they were going to be rotoscoped over, strict photorealism wasn’t necessary.

Could you take us through your production process?

Really slowly. This was my thesis project in college I had hoped to be able to complete the film in a year – it took others and myself two and half years of more or less continuous work to finish. I had made some music videos with this company Glass Eye Pix, produced by Chris Skotchdopole. In the spring of 2013 I storyboarded the whole movie and Chris and I brought it to Glass Eye’s owner Larry Fessenden, who agreed to give us some money to film the live action part. I raised the rest of the money for production by selling an antique music box I had inherited to a collector. I built the set in a week and a half in a studio we had available at my school, Bard College. Principle photography was 4 days with one day of travel. Of course about half the movie is composed of little macro inserty shots which I gathered slowly over the course of the next two years.

Once I had done some editing and VFX work on the film, Chris and I used that footage to create a Kickstarter campaign to raise money to complete the VFX and rotoscoped animation. I used the money to hire my friend from high school Auden Lincoln Vogel and his friend Annelyse Gelman to get me over the hump of the VFX and rotoscoping. By the time of my graduation, the spring of 2014, we had completed almost all of the VFX but still had more than half of the rotoscoping left to do. So I moved back in with my mom in Richmond California and worked out of her garage for the next 10 months. I also asked Larry for a bit more money so I could hire my cousin Carter to help me for a few months. During this time my dad supported me for food and things like that – I tried not to take it for granted and work at least 50-60 hours a week on the animation. Finally by May of 2015 almost all the animation was completed. I moved back to New York and have been working off and on as a freelance cinematographer and visual effects artist. I met Geoff Saba, who did the music for the film, through a mutual friend. He worked off and on on the music from July 2015 to early January 2016. Arjun Sheth – who did the sound design started working in October. During Christmas and New Years of 2015 I did the remaining piece of animation: the credits. The last frame of the credits was finished only a few days before the premiere of the film at Slamdance in late January.

How did that process translate into the equipment and software you used?

The film was shot on a Canon 5D Mark III. We had a dolly and a few lights – a couple Rifas, a couple Kino Flos and a Lowell kit. A couple other camera rigs I built for the film: for when the camera spins around the couple during sex this was a bicycle petal bolted to the ceiling with a pipe coming out of it and the camera hanging off the pipe with c-stand arms. There was also a pulley rig for when the camera dives from the ceiling into the male figure’s open mouth. Everyone was terrified of these rigs. The actor, Miles Joris-Peyrafitte, wouldn’t let me lower the camera onto him so it had to be filmed in reverse – the camera started in his mouth and was raised to the ceiling.

Visual effects were done primarily in Adobe After Effects and Blender. Each frame was printed out on any number of basic monotone laser jet printers: basically the cheaper the better – I found that if you took the files to a Kinkos or a Staples the prints would end up coming out without any of the laser jet toner texture that was important to me. The film is about media being degraded through translation and time, so I felt the actual frames had to undergo that same analogue degradation process. For the rotoscoped frames (approximately 3/4s of the film’s 11000 frames were drawn over) that was done by tracing each frame with pen and charcoal. Both the print out and the drawing were scanned into the computer – at first using school scanners and then later my mom’s scanner – and then the drawing and the print were combined in After Effects to create the final image.

The Past Inside the Present is being distributed for free through Indie Street via the BitTorrent Now platform. What attracted you to Indie Street’s distribution co-op model rather than going the standard Vimeo route?I”m going to put it on Vimeo in December so the choice never felt like an either or. Is honesty the best policy? I got a small advance for putting the film on BitTorrent and having it exclusively on there for a month. My income has been in a shitty place this whole year so it was really really welcome (if any of your readers want to hire me to do anything, believe me I’m probably game). Beyond that though IndieStreet has been really generous in supporting the film through Facebook and social media. There’s an illusion of a level playing field on the internet – that any one can make something that can “go viral”, but chances are anything that’s been seen by any large number of people has gotten a megaphone through a platform that already has a lot of traffic – so IndieStreet giving me a small megaphone is something I’m really grateful for. Finally – I do enjoy Bittorrent as a platform – it’s refreshingly free of editorial as a platform – they just put cool shit up without a ton of context which I think allows for a really pure experience – I like the idea of people downloading my movie without know very much about it and just thinking “What the fuck was that?”.

The making of archive (included in the premium download bundle) is so detailed, honestly reflective and gorgeous to boot, that I found myself inadvertently reading the entire 70 pages in one sitting. What was your process when it came to selecting and combining all the years of filmmaking ephemera into a cohesive collection? Were you ever concerned about being ‘too’ honest?

I think it started as just writing a short reflection on each stage of the process – I mostly wrote it for myself so I can remember what this period in my life was like in 20 years. I also thought – once someone has had this chance encounter with this short film, if they are interested in knowing my thought process behind it they deserve it. I’m very skeptical of the notion that art is this mysterious process and the artist needs to be kept behind a curtain like the Wizard of Oz. I vaguely feel like – artists shouldn’t have to be able to explain their art completely but if you can’t say anything meaningful about the thing you made there’s a seriously decent chance you’re full of shit. My girlfriend encouraged me to organize the whole book a little bit more explicitly chronologically to help keep readers oriented. In terms of my selection: there wasn’t a ton of stuff to choose from. Pretty much all the material I had ended up in the book.

I don’t think I was concerned about being too honest – again this a book that I expected to be read by 20 people max: it was a surprise to me that IndieStreet wanted to make it part of the bundle. I guess the most embarrassing part of writing the book is admitting how much privilege you need to make a film like this: you basically need the luxury of sitting in your mom’s garage working for a year and a half. And that’s something that few people have. But I think that’s an important thing to say as well: if you like this kind of filmmaking, and you care about it, you can’t expect it to get done on the ordinary mercenary production cycles that have become the norm. Part of the reason films can be feel homogeneous is because the process by which they are made are homogeneous – so many tropes in filmmaking come from what is expedient to the process that is taught in film school. So many decisions get made because “We have to make our day” – coverage gets simplified, and the structuring of a film shoot becomes increasingly military – every conversation becomes a conversation about efficiency. Giving yourself time is the only way to emancipate yourself from the homogeneity of these processes. But having time is a huge privilege – and it is a little uncomfortable to say “Hey look at what I was able to accomplish with my privilege!”

Years of man hours and determination to move towards your goal went into the creation of The Past Inside the Present, what effect do you think the extended period of time had on the project and on you as a filmmaker?

To contradict what I just said a little bit maybe, I think the effect hasn’t been totally great on my post-PITP work generally: once you become used to moving an a very glacial pace that easily can translate into complacency. I’m working on a couple music videos at the moment but I think my work has lost a little bit of urgency and structure because with PITP I blew through so many deadlines that the psychological effect of having a deadline just lost its power. Once you’ve worked on something for a year and half longer than you originally planned to it’s hard to give a shit about being behind. I’m trying to change this – trying to be a little harder on myself and demand more broader strokes and more progress out of my work. I also think – and it’s hard to tell if this is related to making the film or not – but I’ve become a little more numb as a person since beginning the film. Beginning the film I was working my way out of some depression, but the channels of feeling were definitely more open. Spending 2.5 years of all work and all play (since really tracing frames never felt like serious work) has made me a little bit of a dull boy.

Are there any new projects you’re productively procrastinating about at the moment?

Well like I said – there are the two music videos I’m working on right now. And I’d like to make more – if I can find some way to make it make any kind of financial sense, which right now it does not. Just like every other creative I have feature length script I’m working on: it’s a coming of age story set in an alternate 1979 Portland OR, where sex is physically very different, and where the friendship of two young women catalyze a series of radical bodily transformations. And there’s another vaguely Past Inside the Present-ish idea – more diaristic and explicitly personal but an extension of the rotoscoping techniques I played with in PITP. It’s another one that that is at its core about transformation of human anatomy.

Top | Link

RogerEbert.com

Collin Souter 4/5/17

SHORT FILMS IN FOCUS: “THE PAST INSIDE THE PRESENT”

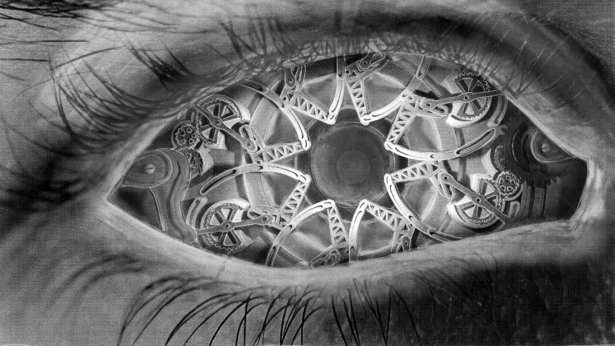

James Siewert’s 13-minute short film “The Past Inside the Present” is like a Laurie Lipton drawing come to life. The stunning black-and-white imagery of humans connected to recording devices via old wiring from their brains to an old Betamax is the sort of thing Lipton would dream up for one of her insanely intricate pencil drawings. This is not to suggest Siewert’s film is derivative. On the contrary, Siewert’s vision aims more for an emotional connection between the characters (even in what appears to be the absence of emotion) whereas Lipton often revels in the absurd and grotesque.

Siewert’s project concerns a couple who, without saying a word to each other, plug themselves into recordings of their memories as their relationship appears to be dying. The tops of their heads are then removed to reveal a series of plugs and wiring that connects to an old Betamax that has tapes from their past. They are soon either watching or are recording an intimate encounter of themselves until the transmission is interrupted. It’s a visual idea that seems wrapped in absurdity until one realizes that we’ve all fallen into this trap of relating our memories and emotions through technology.

It’s the kind of short film that sucks you in just with the visual language. Siewert’s film is black-and-white and uses pen and charcoal drawings that create hypnotic images. Geoff Saba’s score is a nearly constant drone that perfectly complements the synthetic reality Siewert has on display. One moment that sums up the theme of the film is the image of the couple sitting on the bed naked while the word “DISCONNECT” can be seen on the TV screen behind them. Once they plug themselves in, the transmission takes effect and they become tuned into each other.

Both Siewert and Lipton have incredible patience when it comes to their art. Just as Lipton will spend months on a single pencil drawing, Siewert spent a couple years by himself in his garage rotoscoping 7,000 frames to put together this lovely, bizarre and confounding work (he had a small crew helping him at first). “The Past Inside the Present” is an erotic, strange and haunting film that is a constant feast for the eyes.

If I had to guess your inspiration here, I would say Philip K. Dick with a trace of Richard Linklater’s “Waking Life” and David Lynch. Is there any accuracy to that? How did this come about?

It’s hard for me to draw a straight line between any one source of inspiration and the final product. The kernel of the idea was just visualizing these bisected heads with analogue circuit boards in them.

I watched a lot of cyberpunk movies as a teenager (when I originally had the idea)—“Ghost in the Shell,” “Akira,” “The Matrix,” and “Videodrome” as well as Chris Cunningham’s video for Bjork’s “All is Full of Love”, and so all these images of bodies being transformed and fused with analogue technology were sort of buzzing around in my head. The images from these films I’m sure commingled in my mind and formed the technological iconography of the film.

The narrative arc came to me in pieces over the next several years as I navigated college. From the beginning I knew that the circuit boards in the character’s heads would allow them to mainline some kind of sexual experience, but as I disconnected from my friends from high school and home I had the idea of using the circuit boards to have the characters (try to) reconnect with the past. Then the film became much more about an imperfect degraded nostalgia, and how relationships become empty rituals through repetition.

As far as “Waking Life” and other rotoscoped films are concerned—I certainly knew it had been done. I actually haven’t seen all of “Waking Life”—I have seen all of “A Scanner Darkly”—but in all honesty I never liked the look of these films. The appeal of rotoscoped footage to me was the hypnotic flickering vibrations of the images, that I feel induces a trance-like state. The Linklater films have some of that but the animation seems so smoothed over that it feels like a lot of the 24 frames-a-second rhythmic pulsing is lost. There’s an animator who went to my college a few decades ago, Jeff Scher. He does much more aggressive rotoscoping work with a lot of bright primary colors. I would say I was more influenced by this style of rotoscoping than the ones that have been made into feature length films.

The concepts also remind me of the intricate drawings of Laurie Lipton, who often infuses human bodies with technology. I feel like you two are kindred spirits with how much time and effort you put into your pieces and the themes within them. Is there an overall statement about technology and/or relationships you want people to take away from this film?

I don’t think it’s a statement about any particular era of technology—since the beginning of language, and certainly written language we felt we have the ability to access the past through media, so it’s not new.

I guess that’s what I want the film to highlight, is that though technology can more and more accurately simulate for us the experience of the past, these simulations are just a seductive illusion and obscure the truth that we are inescapably trapped in the present. I hope the film communicates something of the melancholy of realizing you are not free to travel to the past, and can only view the world through the pinprick of the present.

I looked at some of Laurie Lipton’s work. It’s incredibly beautiful. I do draw in my free time and I feel like I’m always trying to master what these drawings do so well, which is present a world which can draw you into the finest detail and yet still hold up compositionally on a large scale. I think my drawings just tend to look like a mess from far away.

Getting back to the time consuming process of drawing over 7,000 frames, what was that process like? What kept you going?

The process was challenging in the way you might expect: it was hundreds of days of monotonous work that only changed very gradually. But it kind of suits my personality type. I do well with very gracious but steady progress, as long as I’m moving forward at a constant rate the speed doesn’t matter. In fact all things being equal I prefer to move slowly; I get overwhelmed easily so feeling like you are tackling a film one frame at a time is very comforting to me.

Rotoscoping allows you to operate on auto-pilot mentally. I listened to a lot of podcasts and audio books during the making of the film: a lot of Murakami books, all of the “Game of Thrones” books, War and Peace, etc.

I definitely did slow down in the second half—it does start to feel endless at a certain point. But I think the thing that kept me going was just how much of an asshole I would be to waste everyone’s time on the film if I didn’t finish it.

Technology geeks like me will note the Betamax player. That device could have been anything. So why Betamax?

Well, like I said—I’m a big fan of “Videodrome”and that era of technology—the idea of a circuit board bisecting people’s heads only works if you have some kind of slightly analogue technology driving the whole thing. So that narrows it down: it has to be some sort of tape-based format that goes out to RCA or component cables. In terms of the Betamax specifically I just liked the look of the tapes: they have just one circle like a cyclops. There’s a theme of circles in the film—and narratively the film depicts just one cycle in the repeating loop that the characters are continually moving in. So the single circle of the Betamax tape seemed like it reinforced this iconography of circles and loops I was trying to create.

What has the response been like at festivals?

I think the response has been mixed? You never really know because you don’t hear from people that don’t like it. But I’ve been rejected from a lot of the big American festivals, so I think it’s obviously not a complete crowd-pleaser. At least one festival gave me feedback about why they ultimately rejected—but I’m not sure I’m allowed to talk about that. I think some people find it slow and a little pointless.

However, ultimately you end up having conversations with people that do connect with it. The film was screened to a mostly elderly audience as part of a lifelong learning class back in January. At the end of the screening a woman came up to me—I think she was in her late 70s—and told me that she was a writer and that she was losing her memory, she would forget words more and more frequently deeper into her old age. She said that she related to themes in the film of losing the past despite one’s best efforts to preserve it. It’s cliched to say but the moment of connection I had with that woman made me feel like making the film was all worth it. I make these things as a way to give voice to my private anxieties and fears and it’s always gratifying to know you aren’t alone.

What’s next for you?

I’ve been working as a cinematographer and visual effects artist for the past year and half or so. The first feature film I worked on as a cinematographer, “Like Me,” just premiered at SXSW a few weeks ago. It was an incredibly steep learning curve but I think the film ended up being pretty interesting. Right now our whole company is gearing up to shoot a new thriller. In between these projects I try to direct music videos or draw. But no one wants to pay me to do those things as of yet, or at least, I haven’t been able to make it work yet.

Top | Link