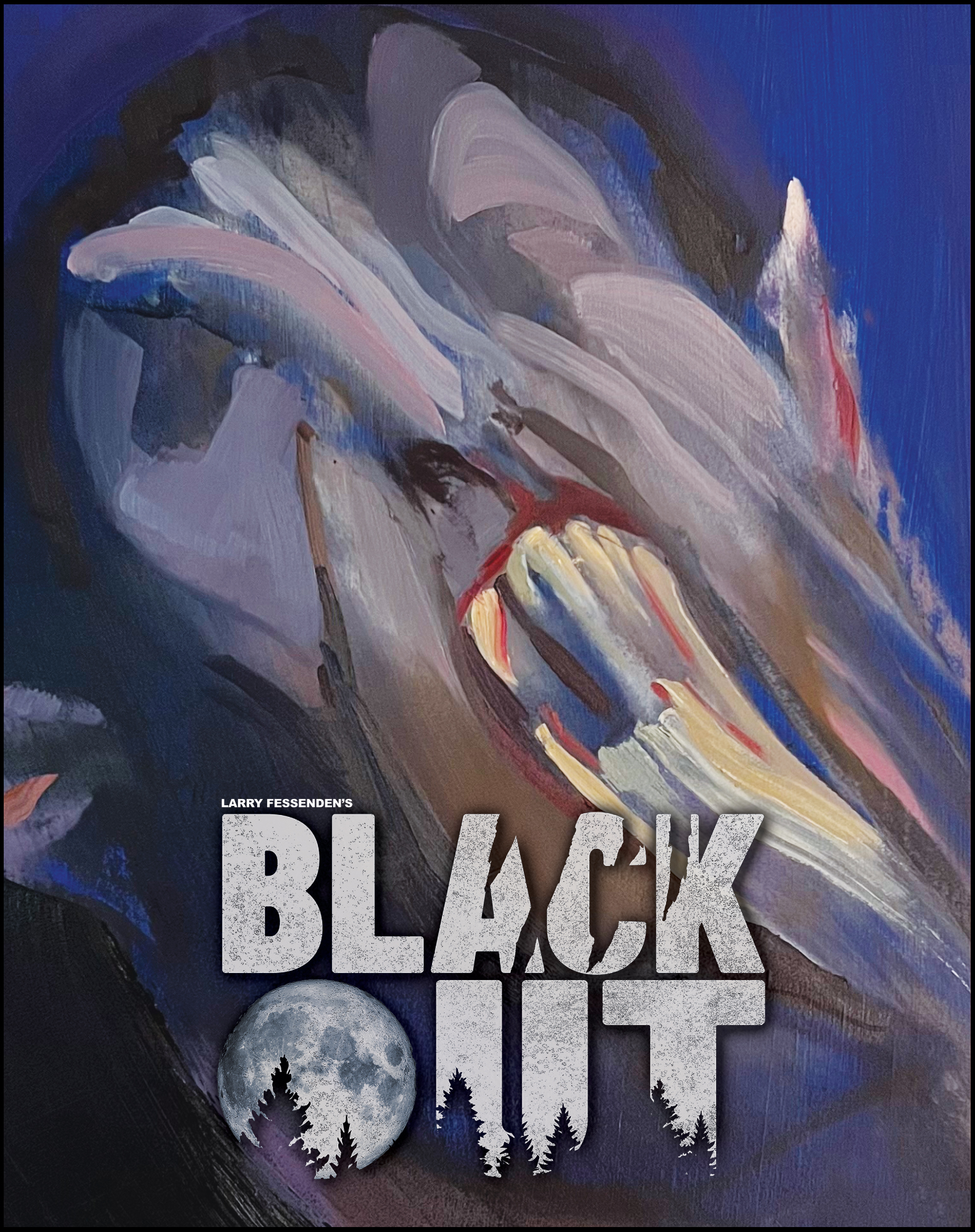

Larry Fessenden reveals news of his new horror movie “Blackout” and why the genre needs substance to survive.

I am excited to report that Larry Fessenden has wrapped production on his seventh feature, “Blackout,” which stars Alex Hurt as a painter in a rural community who’s convinced he’s a werewolf. If you don’t know Fessenden’s work, you may as well remit your horror buff credentials now — or keep reading, because the persistence of this filmmaker’s lo-fi approach to horror over 40 years is a case study in its own right.

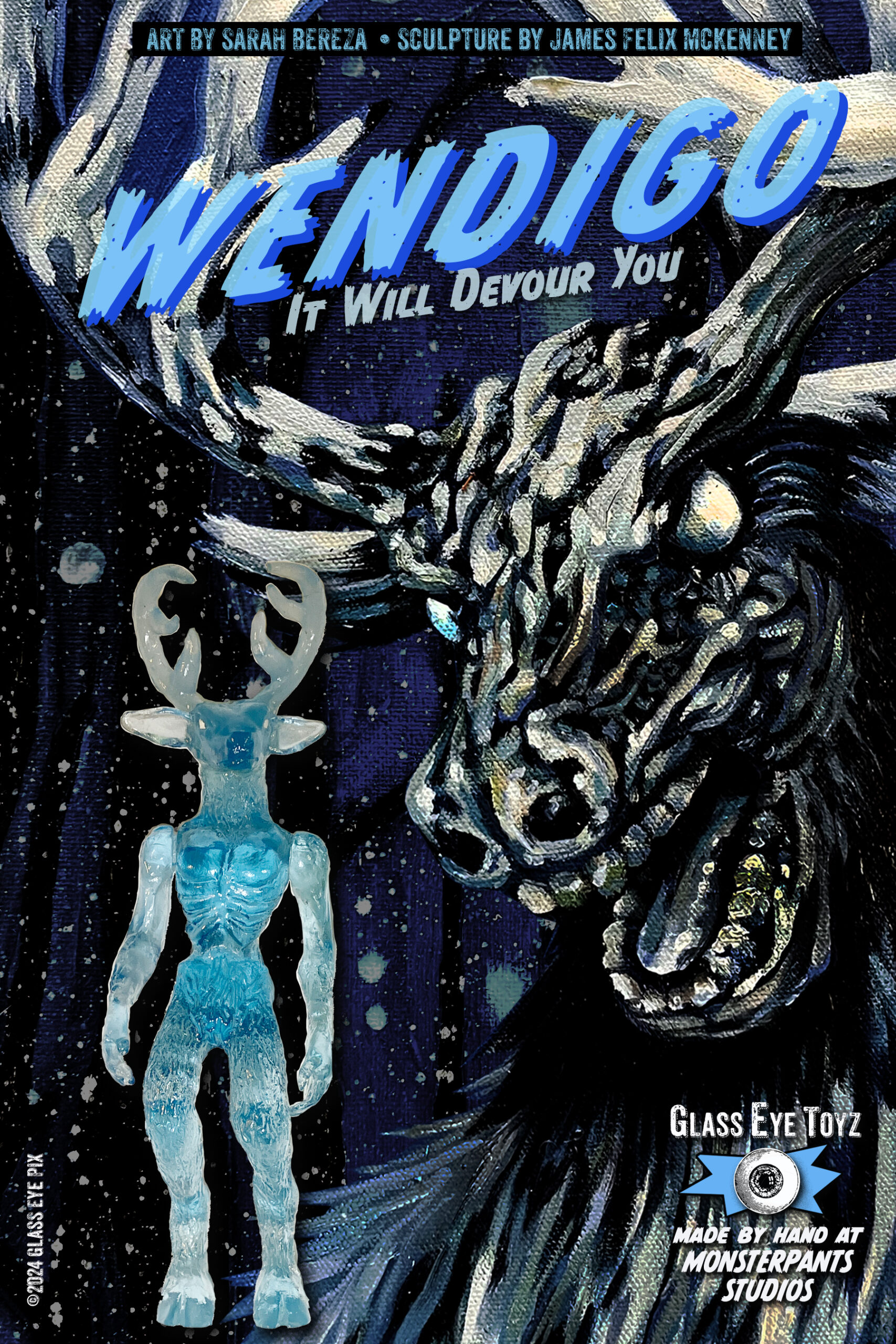

On the subject of horror movies with something to say, well, that’s what the 59-year-old Fessenden has done for generations. At 22, he launched his New York production company Glass Eye Pix and he’s built a remarkable filmography out of spooky horror movies doused in social commentary. (You can also thank him for serving as a producer and general advocate of fellow New York filmmaker Kelly Reichardt.). With the very recent exception of Jordan Peele, nobody has mined more for substance in modern monster movies than Fessenden, but the industry has yet to embrace his work to the extent it deserves.

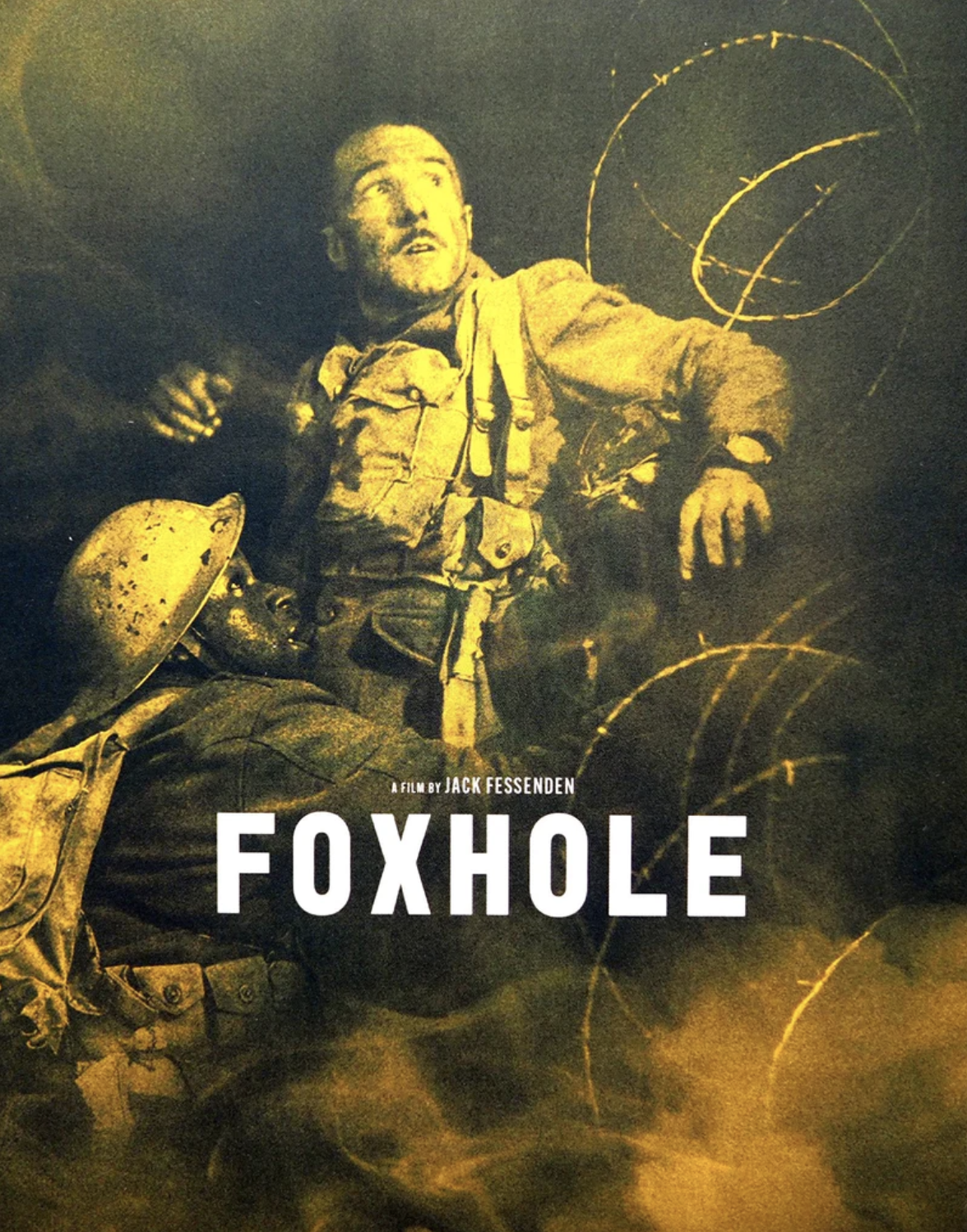

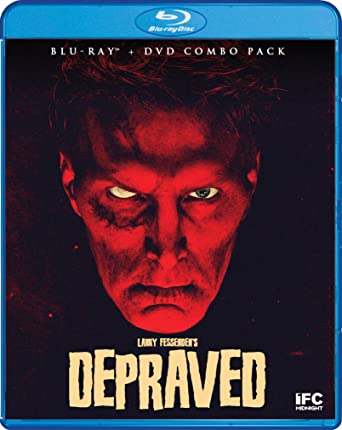

“I’ve been living in this world of low-budget impatience for years,” Fessenden told me over Zoom this week. After spending nearly a decade scraping together the budget for his last movie, the stellar 2019 “Frankenstein” adaptation “Depraved,” Fessenden decided not to wait. He took a communal approach to the production, shot in New York’s Hudson Valley with local merchants donating props. He self-financed the production with a handful of investors in part using residuals from previous Glass Eye productions. “I just wanted to skip all the angst on this project,” he said. “There’s a rock ’n’ roll aspect to just going out and making movies quickly.” Fessenden laughed as he declined to comment on the precise budget. “Let’s just say it’ll be eligible for the John Cassavetes Award,” he said. (The Spirit Awards category highlights projects made for under $500,000.)

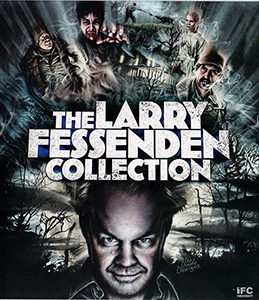

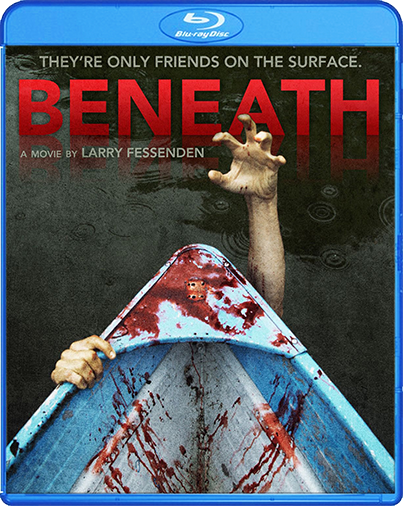

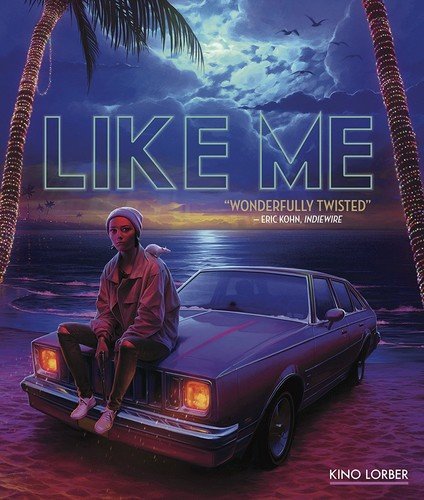

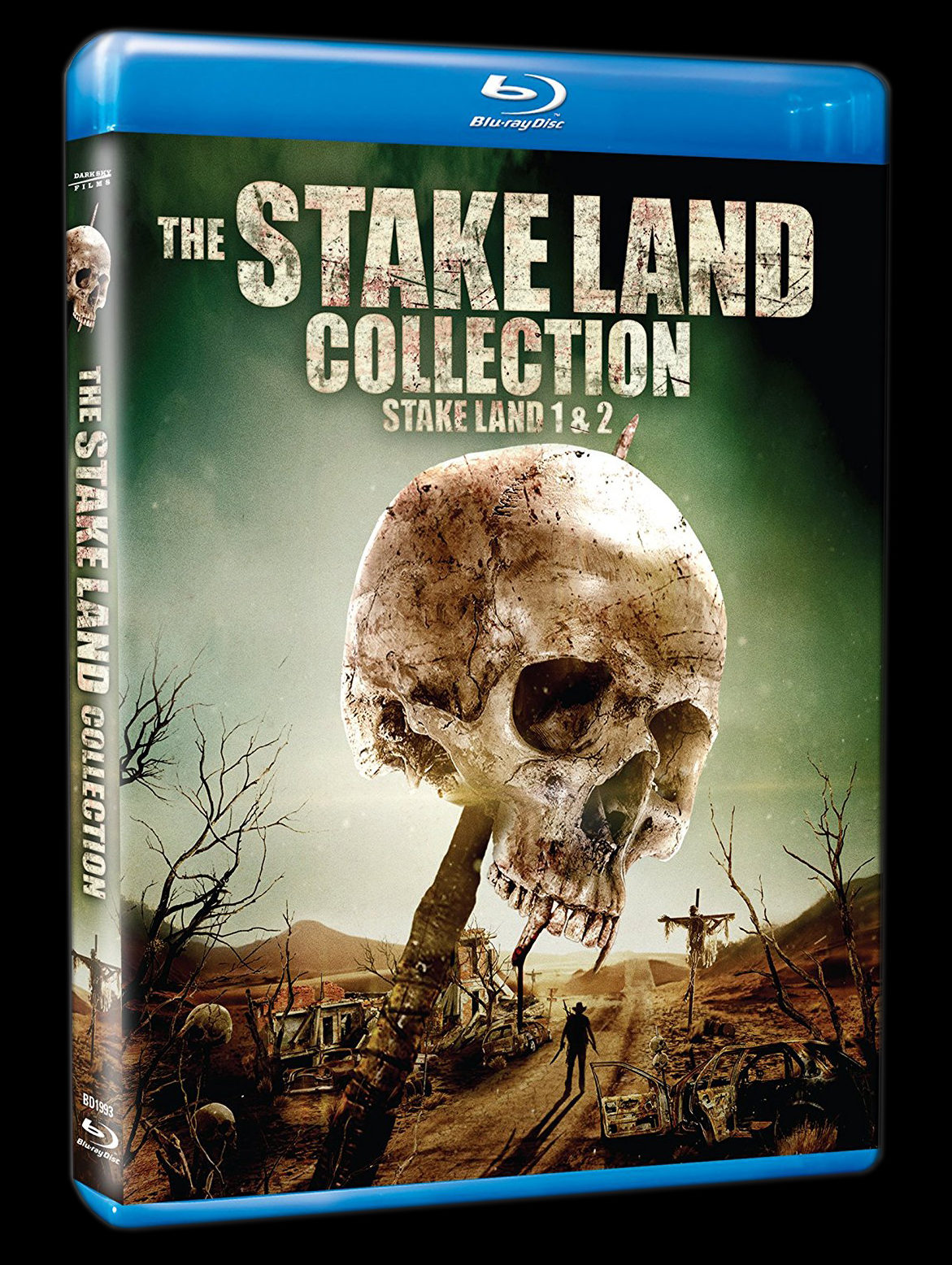

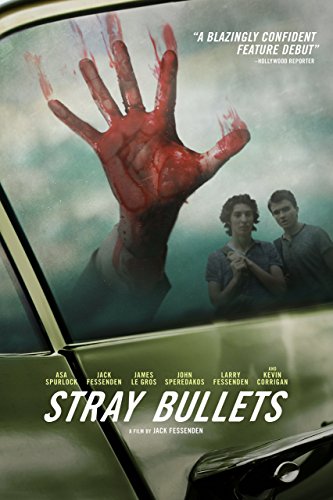

With his missing tooth and tousled hair, Fessenden looks like a genuine creature of the underworld. His movies feel that way, too. Their themes range from global to intimate, starting with the alcoholism at the center of his masterful vampire thriller “Habit” (1995) and continuing through the climate-change allegories of the “Frankenstein”-inspired “No Telling” (1991) and “The Last Winter” (2006). During that time, Glass Eye became a kind of mini-factory for substantial horror stories produced on a small scale, with Fessenden helping launch the careers of directors like Ti West (“Pearl”) and Jim Mickle (“Sweet Tooth”).

The typical Fessenden movie is made for a few hundred grand and looks like it, but not in a raggedy way. The smallness of his movies enhance their intimacy and give the eerie impression of a world coming apart at the seams. When I profiled Fessenden for the New York Times in 2011, I compared his collective and its support of no-frills genre filmmaking to Roger Corman, but Corman ultimately wormed his way into a Hollywood system that Fessenden keeps at arm’s length. “I was never good at the parties,” he said with a chuckle.

After acclaim for “Habit,” Fessenden navigated a number of studio offers that didn’t gel, for obvious reasons: He wanted to bring substance to the genre, and studios wanted market-ready products. They batted away his pitches for “Mimic 2” and a reboot of “The Texas Chainsaw Massacre.” Perhaps the greatest irony from this period is that Fessenden once pitched Miramax genre label Dimension Films an adaptation of Marvel Comics’ “Werewolf By Night,” decades before the MCU took off.

The recent black-and-white “Werewolf By Night” adaptation on Disney+ certainly provides an innovative riff on Universal monster-movie tropes, but it’s more of a superficial homage than an attempt to grasp the fundamental horrors at the root of the originals. “We’ve seen all kinds of werewolf movies,” Fessenden said. “To me, it’s a Jekyll-and-Hyde story, a form of madness, and a lot of my concerns are there. As the political system unravels, do you keep fighting for democracy or just keep leaning into the hysteria?”

Notions like that don’t translate into a tidy pitch deck. “In the end, maybe this is the zone I belong in,” Fessenden said. “I don’t mind. It’s a more organic approach to filmmaking. I have my hands in every department.”

Fessenden wasn’t wowed by the original “Halloween” in 1978, arguing that much of the discourse around that franchise was less about the movie than the life it took on later. “I thought it was just horror for horror’s sake,” he said. “I really liked the metaphorical grit of movies like ‘Rosemary’s Baby,’ whereas ‘Halloween’ was just scary music for the sake of the next kill. It just felt like a spookfest.”

After “The Last Winter,” there was a period when WME represented Fessenden. For a few years, he was attached to direct an English-language adaptation of the Spanish horror film “The Orphanage” for New Line, with Guillermo del Toro as the producer. That project fell apart due to budgetary constraints while the rapid-fire pace of Hollywood’s IP hunger annoyed Fessenden again and again.

“My favorite agent email read, ‘Stephen King’s ‘It.’ Any int?’ He just wrote ‘int,’” Fessenden said. “I wrote back saying, ‘Sure, what about it?’ He’d never respond.” After the “Orphanage” project fell apart, Fessenden found out that his agent had dropped him. “If you haven’t had a hit by now, I don’t think they’re really looking for your cooperation,” he said.

Fessenden isn’t the biggest fan of Blumhouse, which resurrected the “Halloween” franchise among other commercial horror coups. While the company has managed to produce complex horror successes like “Get Out,” there’s a reason why Peele went on to start his own production company.

The Blumhouse model prioritizes low-budgets with the potential upside for key creative forces, but it’s still a factory and that can lead to a lot of rush jobs, like “Halloween Ends.” For all the talk of its box office being hurt by a day-and-date release on Peacock, I suspect this second sequel to a quasi-reboot might have found legs if audiences weren’t already exhausted by yet another “Halloween” movie. “Let’s be honest,” said Fessenden, who has yet to see the film. “We’re talking about the commodification of something that is supposed to be pointed and say something real about society.”

He cited the original “Night of the Living Dead” as the template that all modern-day horror filmmakers should consider. “It’s about society breaking down during Vietnam and the racial struggles of the time,” he said. “At their root, horror movies have to discuss things that are horrific. So I think it’s a problem to commercialize this genre.”

Add a comment