Matt Morrison of Film Comment just wrote a rundown of Mickey Keating’s DARLING ahead of its NYC premiere. See the movie tonight at 9:45pm at Film Society of Lincoln Center (tickets and more info here).

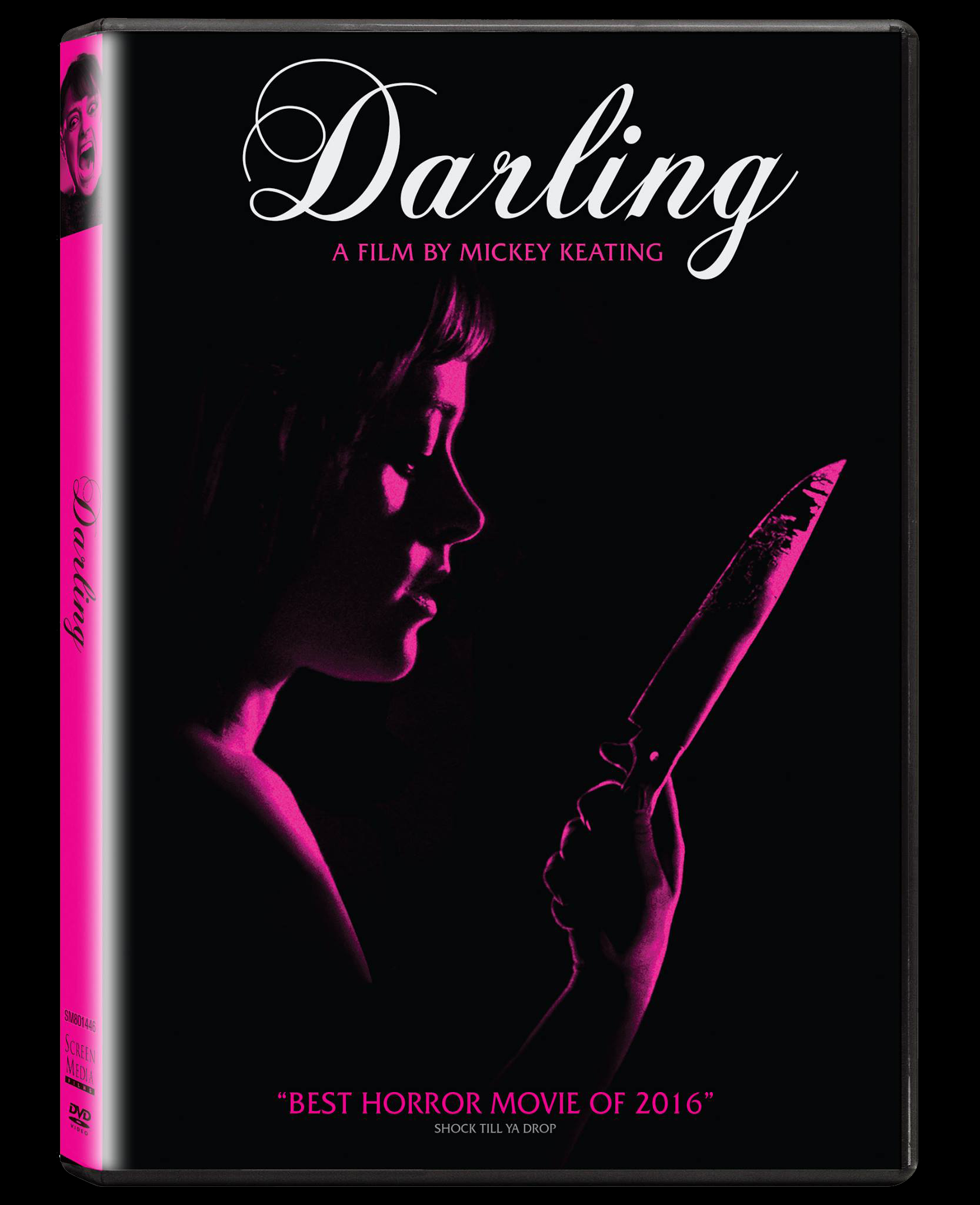

Darling

In Mickey Keating’s menacing new psychological thriller Darling, we meet the titular character (Lauren Ashley Carter)—sporting an innocent flip haircut, silk jabot, and Karina-in-Alphaville raccoon eyes—as she assumes care for an old Manhattan townhouse. It “really is a lovely old house,” the owner (Sean Young) deliciously and beguilingly informs her. “It will take care of you.”

If only it were so simple. Soon, we hear rumblings of previous suicides, devil worship; Darling finds an inverted cross, and happens upon a locked, inner-lit white door. A nameless Gentleman caller (Brian Morvant) pursues, then is pursued by the increasingly unhinged Carter. Whispers and squeals proliferate, and Darling’s nightmares and reality merge, giving way to loss of self, isolation, dread, and paranoia.

In addition to Keating’s disquieting collage, strobe effects, and disorienting shifts in perspective, Darling draws its eerie atmosphere from a score by Giona Ostinelli. Featuring staccato string trills, piano groans, glitches, static, resonance, and white noise, the mix frequently culminates in moments of authentic, deity-invoking terror.

“We wanted each room in the house have its own breath, its own voice,” Keating said. “We used bells, waterphone, contact microphones, and, as reference points, artists like The Black Angels, George Crumb.”

Though it tempts cliché to cite a home, or city, as a “character,” Darling’s apartment is, if not a persona, then certainly an entity. Shot in the verticalizing, claustrophobic aspect ratio of 1:1.66, the interior, at times, seems to verge on 90 percent wall.

“The house was inspired by Ferrara’s Ms. 45—a big, open New York City apartment. In 1:1.66, it came out quite tall, gained symmetry,” Keating said. “The family was quite nice about letting us move in and spill blood everywhere. Probably a lot in that house cost more than the entire crew’s lives.”

Like his Scary Movies peers, Keating sees Darling as a linear successor to horror history: “I wanted this to be a love letter to Sixties experimentalism, the ‘descent-into-madness’ movies. Polanski’s Apartment Trilogy: Repulsion, The Tenant, Rosemary’s Baby. Altman’s That Cold Day In The Park. Kenneth Anger, Eraserhead. Hollis Frampton, Stan Brakhage. The Innocents. The Haunting. I wanted to create a nightmare. A hallucination, without smoking dope.”

For Keating, who’s already at work on his next film (the sedately titled Carnage Park), horror has been less a choice than an object of sacred, ascetic reverence.

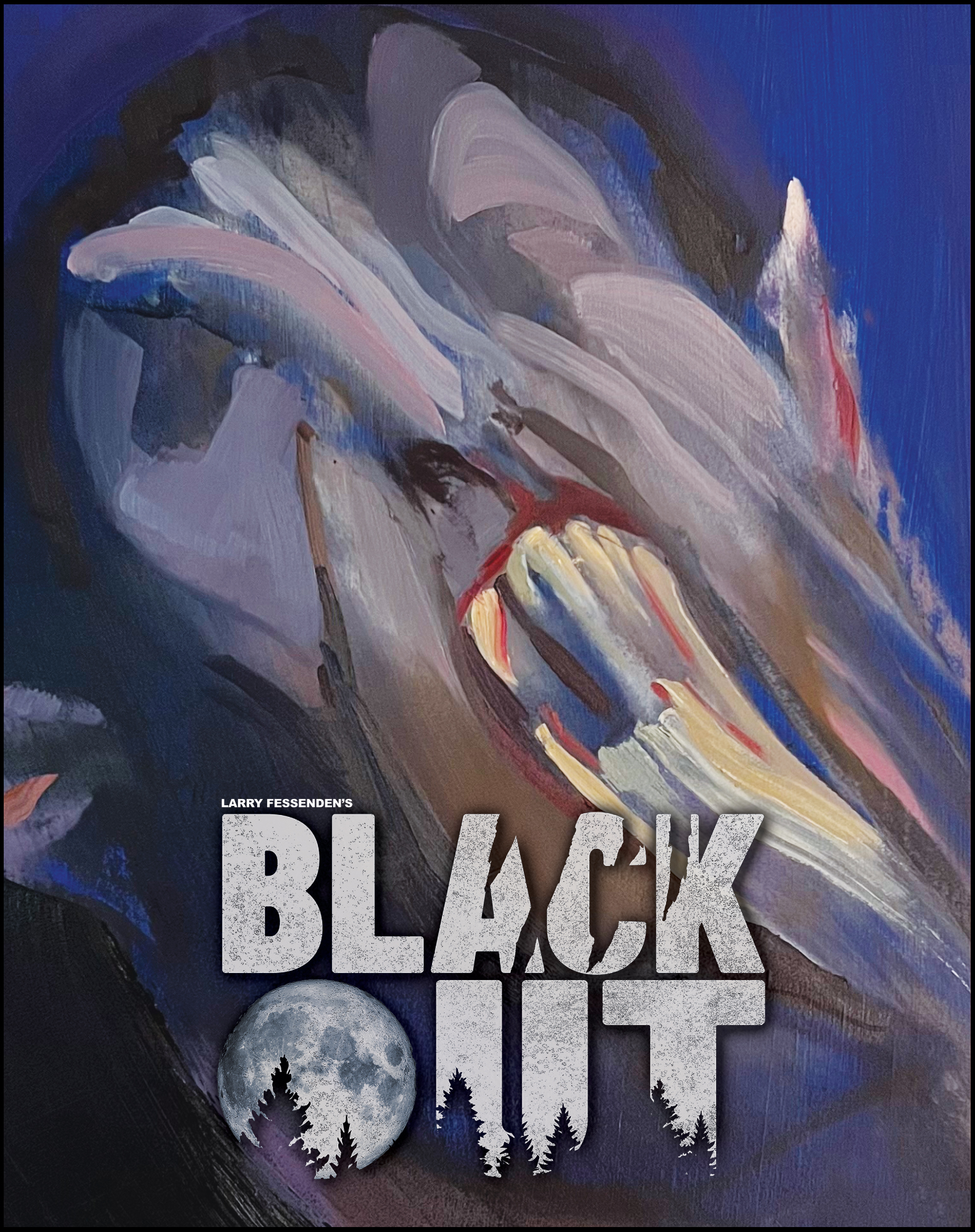

“I started making movies when I was 10. If I wasn’t directing, I would be walking the Earth,” he explained. After an internship at Larry Fessenden’s Glass Eye Pix, Keating began his career in earnest, leading to fruitful cross-pollination with Fessenden since; Fessenden has a cameo in Darling as a police officer. “I’ve been a fan of his movies, and Glass Eye in general, since I was a teenager. When I was in college, I found their number on the deepest part of Google, which was young then, cold-called, and begged them to be a gofer. Over time, I would always hound him to watch my short films. He’s a tremendous inspiration, and I’m delighted to call him a friend.”

As in The Innocents, and many horror movies before it, Darling wisely declines to specify the roots of its lead character’s undoing—whether psychosis, or demonic possession. At Darling’s denouement, one is left wondering: do caretakers ever fare well? There must be better ways to pay the rent.

Add a comment