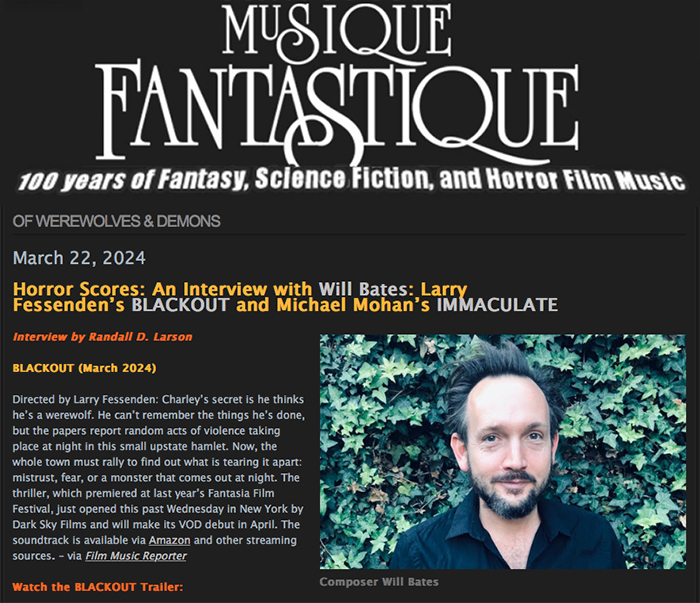

Q: You’ve worked with Larry Fessenden previously, notably on his unique films BENEATH and DEPRAVED, and now with BLACKOUT. What does he look for in music for his movies?

Will Bates: I feel very fortunate that the first horror movie I ever scored was for Larry. He told me a lot about how to work with the genre, and we connected over this sense of elegy and pathos and almost tragedy with horror. I feel like that’s something the filmmaking is embracing with BLACKOUT. Scary things for Larry are more frightening and disturbing if a certain amount of tragedy is involved, and music has a compelling way of portraying that. We’d already developed a great shorthand and language when we worked on BENEATH and then DEPRAVED – this is my third film with him. I consider him a dear friend at this point. One of the great benefits of working with people repeatedly is that you start to trust each other, and he let me play with the tone of this movie and experiment. I adore him for that. He’s a very loved man, as I’m sure you know.

Q: BLACKOUT is a unique werewolf story based on Larry’s audio play of the same name. What was he looking for in the music for this film?

Will Bates: Whereas, with DEPRAVED, he talked a lot about the brain, synapses, and electricity. With BLACKOUT, we wanted to be more organic and more of an expression of the woods and memory. We talked a lot about memory. In the end, the subtext of this film is just that. What happens to a werewolf and the literal blackout of the transformation? So I think, in terms of the instrumentation, it was very organic – lots of horns, woodwinds, and guitars, which is a new thing for me with Larry. We’ve never really done guitars in his scores before. There are no synths, none of that; there’s hardly any electronics. Maybe towards the end, when things get a bit crazy, I’d start reaching for some of those tools, but overall, it’s very raw, Lots of strings – and when I use the strings they were recorded very close to the instrument. It’s a very dusty feeling, natural and scratchy. One thing I could do here that I hadn’t done too much before was… I recently reconnected with a double bass player named Gary Wicks [ https://www.garywicks.com/ ], a jazz musician. I’m a reformed jazz musician myself. Gary’s an excellent upright bass player, and he did a lot of great arco (bowed playing) with his instrument and used his instrument to create crazy crunches and sound effects. Larry always wanted churning, crunching bones – like “let’s get that feeling like the hair is coming out of the skin and all of that stuff, which is so visceral with werewolves. The double bass became a thing that I gravitated toward a lot, and I looked to Gary to work on almost every cue on this one.

Q: I want to ask you about a few particularly interesting cues. “Howl” is just that, a mix of sonic howls and roiling brass, followed by “Jail Break,” which added its own sonic confrontation of sounds…

Will Bates: Wow, that’s a great description! This movie was also interesting in that, while Larry was editing, he wanted a tool kit of stuff, which is a way that we’ve worked together in the past. We’d talk about themes for characters, like the significant tent-pole cues for the movie, and I’ll work on those. But alongside those, he always had stuff to play with, and I tend to write that way, anyway. I’ll throw lots of things at the page and lots of sketches, which tends to be my journey to find those big themes. The sketches always end up being useful, especially with a filmmaker like Larry, who likes to use music while he’s editing, and sometimes I’ll give him the stems for those sketches.

“Howl” was one such thing. I thought of finding recordings of wolves, sketching them, and pitching them to make this an even richer tapestry of layered notes. When you take a howl from a wolf and stretch it, you can identify individual notes and tones layered. I started to write around the shape of the howling melody, and that’s what that piece is. I isolated it into a fifteen-minute section, stretched-out wolf howl, and then orchestrated it. That’s what that piece is, and then added Gary’s bass and a few other things – and then, of course, the horns. Larry’s one of the only filmmakers who doesn’t make me take the saxes out, so I’m always reaching for the horns, knowing he’ll love it! That’s always reassuring!

Q: “Charley’s Theme” reprises the opening “Charley’s Leaving” with a more delicate sound…. along with “The Ballad Of Talbot Falls,” a kind of jazz interpretation of the previous melodic arrangements.

Will Bates: That’s right, yeah. Again, I’m sort of betraying my background a little bit with that one, I suppose. Larry isn’t afraid of that raw emotion. He’d say… “You’ve got this theme, just do it, man! Make it big and bold and as emotional as it can be. I love that; it’s a wonderful note for a composer to have.

Q: The concluding song nicely completes the film, with Charlie singing a personal ballad that sums up his experiences throughout the story. How would you interpret the movie yourself from this perspective?

Will Bates: I think, for me, there’s such a sadness about the werewolf. Having to leave that life behind and not even having an awareness in your waking state of what you have been enjoying as this creature. That’s the feeling I get – this sense of regret and longing. It’s deeply sad. I can’t think of a werewolf movie that’s not that way. It’s a certain kind of tragedy, and there’s a beautiful love story in this as well, and having to leave here behind. So, yeh, I think loss, and that was kind of the brief, too, this elegiac idea that we’re left with in the movie.

Add a comment