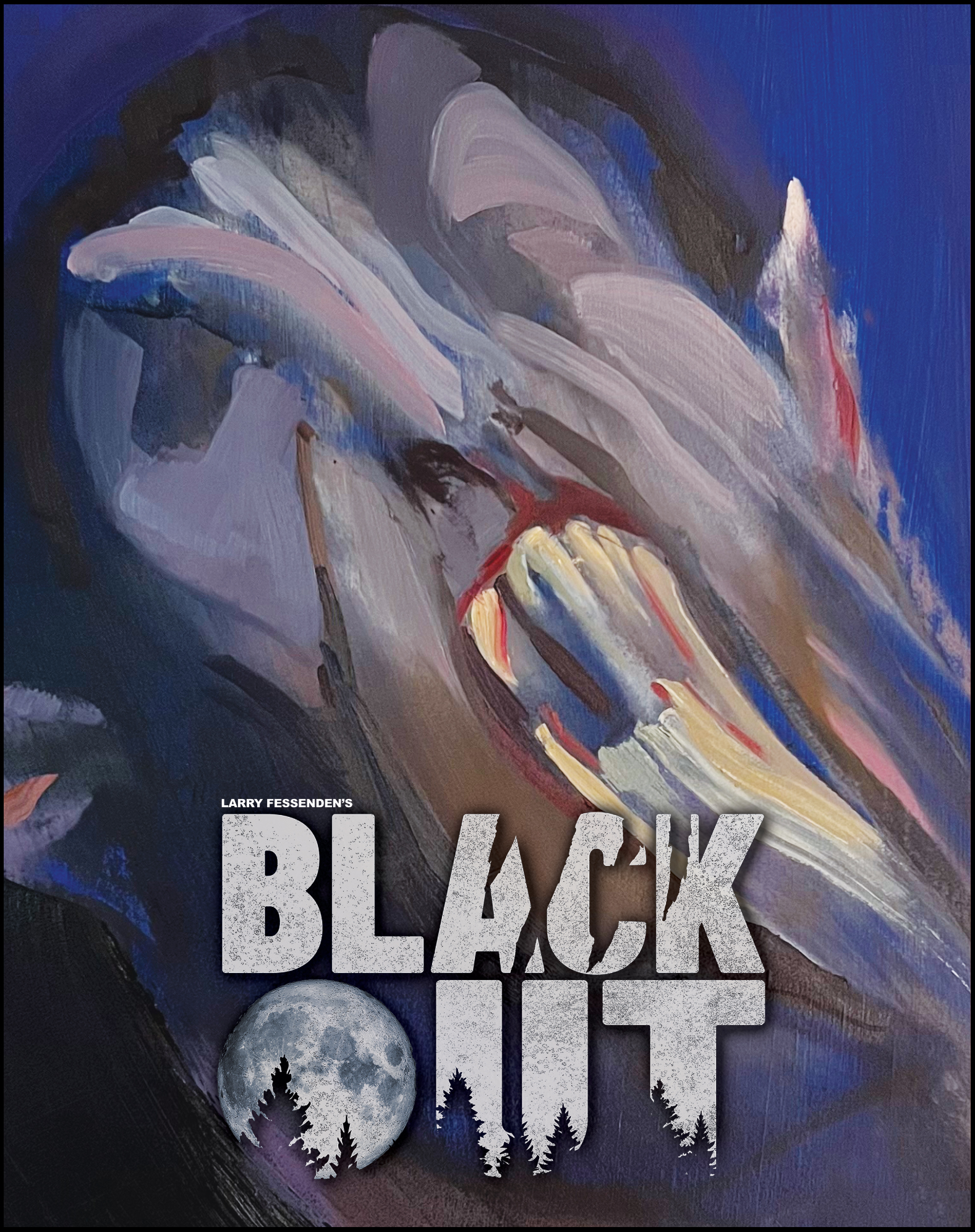

Director Larry Fessenden is not done finding new truths in the classic monster tropes of his youth. He explored the story of Frankenstein with Depraved, vampires with Habit, and is now onto werewolves in his latest film, Blackout. In Blackout, Charley’s secret is he thinks he’s a werewolf. He can’t remember the things he’s done but the papers report random acts of violence taking place at night in this small upstate hamlet. Now the whole town must rally to find out what is tearing it apart: mistrust, fear, or a monster that comes out at night.

Coinciding with nighttime falling, the full moon rising, and an animalistic beast being released, a common reoccurring element found in werewolf movies is unique cinematography. For Blackout, Fessenden brought on director of photography Collin Brazie to map out the look of the film, which he describes as both natural and stylized. Getting inspiration from films like Fargo and Chinatown, Brazie approached the film with a somewhat understated 70s aesthetic. He explains, “It’s a bit loose and gritty at times. Sometimes the best approach to good material can be quite simple”. The end result is a modern take on the monster film. In the below interview, Brazie goes more in-depth about his work on Blackout.

DC: How did you become involved with Blackout?

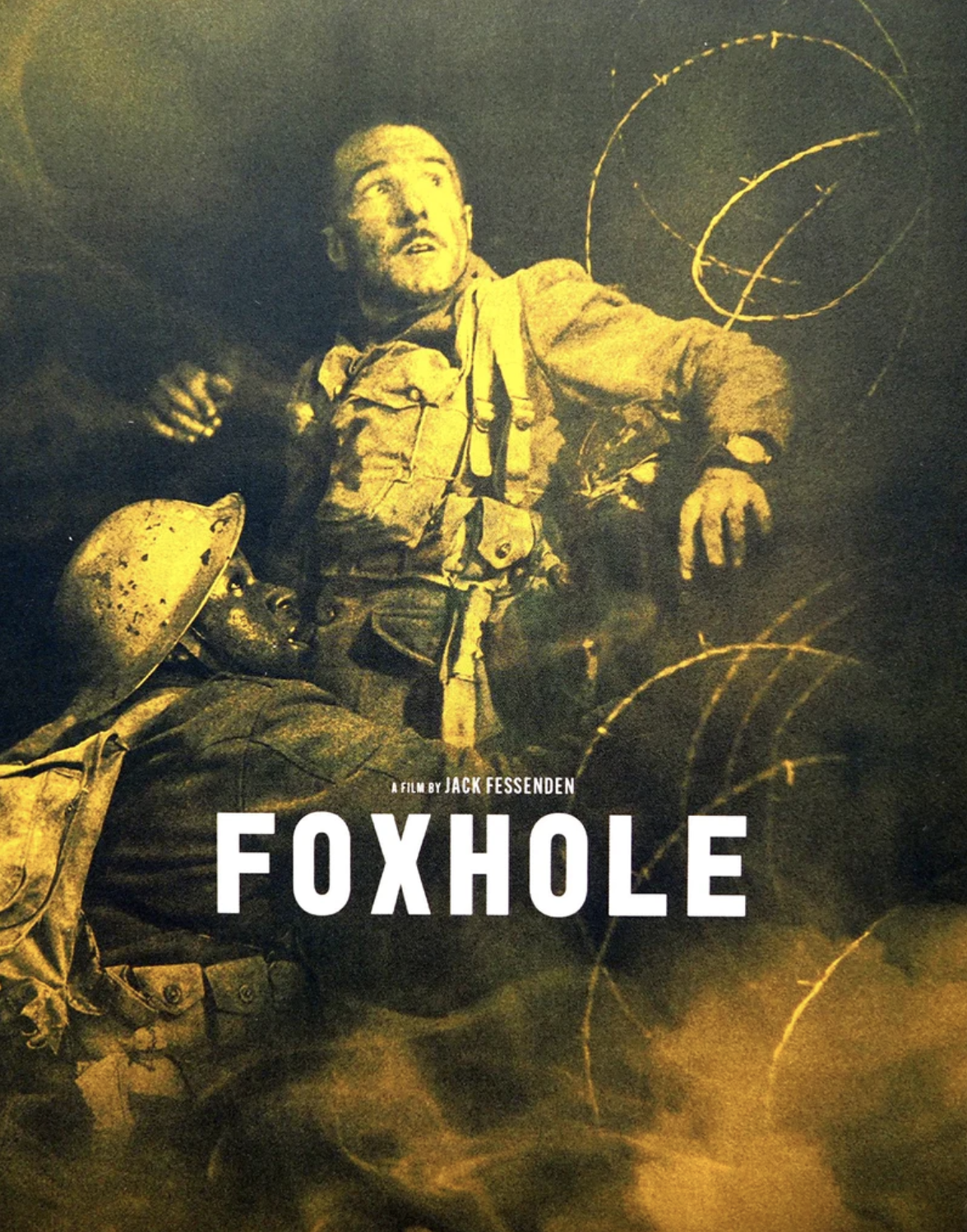

Collin Brazie: I became involved with Blackout because I had worked on a previous project with the writer/director Larry Fessenden. I shot the film Foxhole that he produced via his production company Glass Eye Pix. We got along really well during the shoot and I suppose he liked my work so he sent me the script for Blackout. I was very excited to read it and of course was very interested in the approach to a werewolf story.

DC: How did you work with Blackout director, Larry Fessenden, to find the right look of the film?

CB: Larry and I had a nice amount of prep time before the film commenced, which is crucial when you’re shooting a low-budget film. I always try to be as prepared as possible so that you’re making the most of your time and not wasting precious minutes on set discussing a plan for a scene. I feel that being overly prepared allows you to loosen up a bit on set and try new ideas in a scene that may have popped up that morning.

Larry and I discussed the overall look of the film and each individual scene at length. We knew we wanted certain parts of the film to be handheld and certain parts of the film to be more controlled and fluid. Our main character, Charley, who is a struggling alcoholic, is erratic at times and we wanted the photography of the film to reflect that. Between the addiction issues and the fact that there is a werewolf on the loose – we wanted the camera to reflect the tension that Charley and the other characters were feeling. Of course, this is juxtaposed with a calmer and more controlled camera when Charley and the other characters are more at ease.

I approached the overall look of the film from a very natural starting point – attempting to give a grounded sense of realism to the supernatural story. Especially in the beginning of the film and through the second act I wanted to use the lighting to help ground the story. As the film continues, we let loose and become a bit more stylized. I think this offers a nice contrast between the two approaches: naturalism vs heightened reality. It’s interesting shooting a horror film where the film takes place about half during the day and half at night. I think it makes the night scenes feel darker and a bit scarier when they are contrasted against the daytime scenes.

I think the overall look of the film has a bit of a 70’s aesthetic and is somewhat understated. It’s a bit loose and gritty at times. Sometimes the best approach to good material can be quite simple. We definitely took some cues from films like Fargo and Chinatown and let naturalism lead the way.

DC: The early Universal horror films provided inspiration for Blackout. Can you elaborate on this?

CB: Larry and I are both fans of the Universal horror films of the 1930s and 1940s, notably Frankenstein (1931) and The Wolf Man (1941). What is wonderful about these films is that yes, they are about monsters, but they’re really more about society and humanity (or lack thereof). I know Larry’s films also deal with this idea of what is going on in society and what might be plaguing it at the time. The Wolf Man was a big inspiration in not only the design of the werewolf itself (less snout and doglike – more human characteristics) but also a bit of the structure of the screenplay. It has nice little nods to the tropes of small-town villages, preachers, and the villains within.

From a visual standpoint, we did reference a bit of fog, nature, and night exterior shots from the 1941 film, but it has all been updated for a modern take on the monster film.

DC: Barbara Crampton is somewhat of a horror icon, starring in everything from You’re Next to Pulse Pounders (1998). Can you talk about working with her on Blackout?

CB: Barbara is an icon and an absolute delight to work with. Very laid back and a pleasure on set. She and Larry have worked together a few times, most recently in the horror flick Jakob’s Wife. Since they are friends, she was happy to come shoot with us for a day on our film.

DC: In your opinion, what’s the best way to shoot a werewolf to make them look as menacing as possible?

CB: Haha, good question. I think shadows are key to making any monster or villain menacing. It’s all about where you put the light.

DC: You have no shortage of experience in the horror world. What sets this genre apart from others in how you approach your work?

CB: What is great about the horror genre is that you are able to bring so much creativity to the storytelling. Because it is supernatural you can get away with trying different ideas in lighting, composition, shot design, etc. No idea is too crazy; in fact sometimes the more nuts it is, the better. Even on a film like Blackout that takes a lot of its photographical cues from realism, you still get to take some creative license when stuff starts hitting the fan; how shadowy locations look or how much contrast you have on an actor’s face. When you’re approaching material, it all starts with the script and the characters—and in great horror films, those still come first.

DC: You used a lot of red and blue hues in the film. Can you talk about your thought process behind this?

CB: One other large aspect Larry and I discussed a lot in pre-production was what we wanted moonlight to look like in the world we were creating. Both Larry and I have a big aversion to the idea of this deep blue or steel blue moonlight that was very prevalent in the late 80s and early 90s. It feels a bit hyper-real to me and even though we were making a werewolf movie, a lot of our approach lighting and camera-wise we wanted to come from a place of realism. We wanted more of a silvery moonlight, with just a hint of blue to it. We both felt that held a sense of realism of what a full moon actually feels like.

Obviously, a film about a werewolf always has a bit of a ticking clock to it. The sun is setting, the moon will soon rise. But ironically, we wanted to use as little moonlight as possible. Whenever we were shooting night exteriors, we chose to use practical motivation from whatever sources may be in the scene, such as headlights, streetlights, etc. Only in situations where the moon was the only practical source in the story did we elect to use moonlight to motivate the scene.

We were able to play around with color a fair amount in this film. A lot of the red throughout the film was motivated by practical sources in the scenes.

DC: A lot of Blackout takes place outside at night, under moonlight. What would you say is the hardest part of filming under these circumstances?

CB: The hardest part of shooting night exteriors where only moonlight exists is exactly that – trying to make the moonlight look realistic, so that the audience will buy into it. Obviously, all moonlight is unrealistic to an extent, you’re taking artistic license with the idea of moonlight motivating a scene. But in a werewolf film, it is very important that the moon feels full and big. I think you have to decide where the moon is to introduce a nice edge light. Then the difficult part is how much or how little fill light to bring in.

For our purposes of lighting moonlit night exteriors, you’re attempting to make the world feel larger than it might be, and on an indie budget that is always tough to execute. But I am happy with the way it turned out.

DC: What are you most proud of in relation to Blackout?

Blackout was a very ambitious project. We shot on a pretty modest budget and when shooting indie films they always say “limit your locations, limit the cast size, don’t work with kids.” Well, we did the opposite. We had like 20+ locations and 20+ speaking parts. So for the first half of the shoot we were doing multiple company moves each day. It means you don’t have time to burn. You have to move fast and trust your instincts.

Add a comment