Excerpts from Adam Nayman’s review

Wolf Like Me March 19, 2024

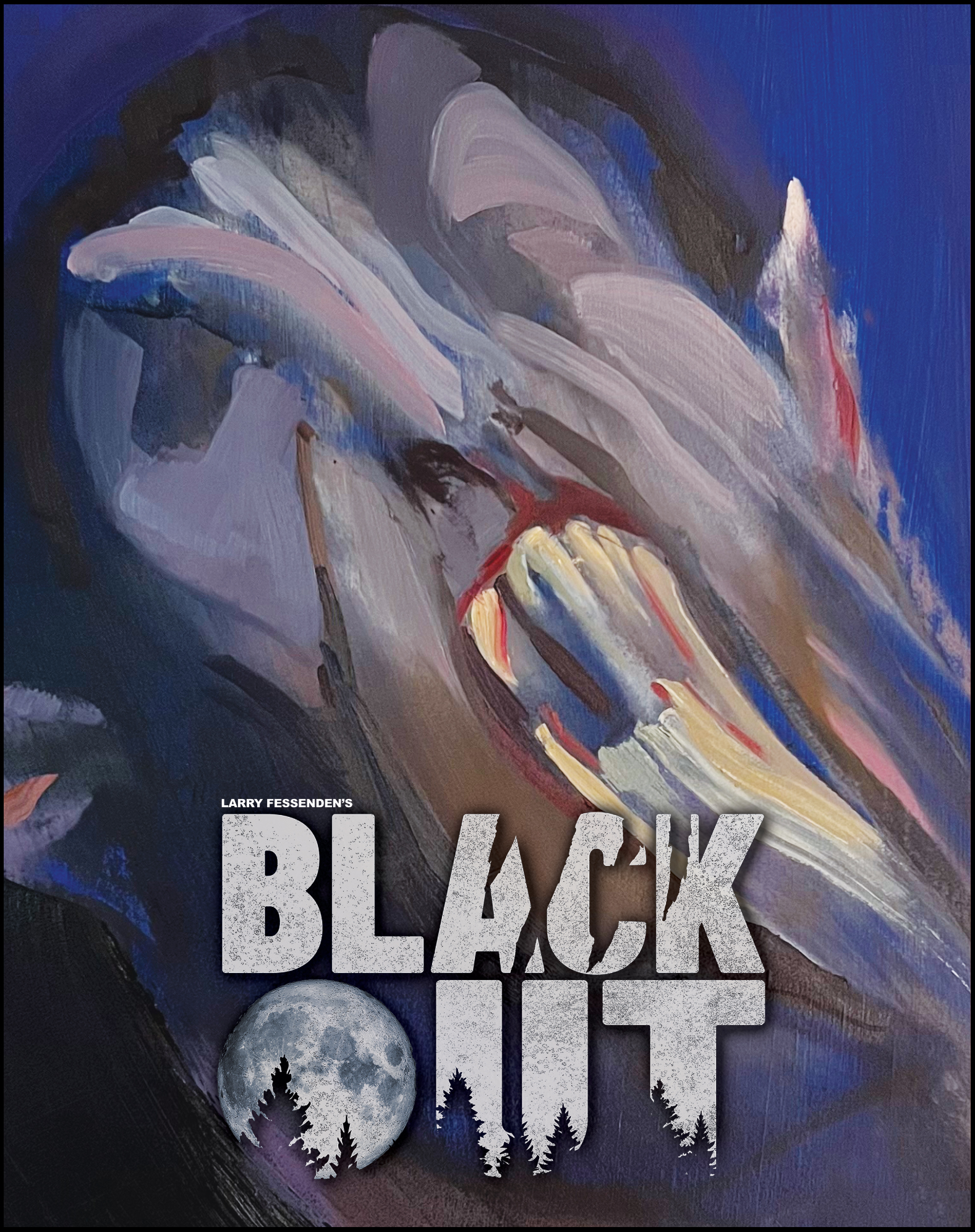

… Blackout, the director’s most striking feature in decades… a nicely atmospheric, sturdily crafted creature feature with any number of intriguing entry points—not least of all that its story of an isolated, multicultural community with predators in its midst exists in indirect but loquacious conversation with Martin Scorsese’s Killers of the Flower Moon. Can you find the (were)wolves in these pictures?

… In more ways than one, Fessenden’s seventh feature is a shaggy-dog story; what binds it to Scorsese’s masterpiece is the way it interrogates certain all-American narratives to expose their ameliorating artifice.

… Fessenden, whose first student movie was a homemade remake of Jaws, has always worn his bleeding heart on his sleeve (in the best Romero tradition). Blackout’s political commentary isn’t subtle, but it’s so deeply woven into the fabric of the material that it feels like an artistic starting point instead of a market-savvy flourish. The theme—endemic to both werewolf stories and activist allegories—is transformation, and while Charley’s efforts to control and channel his condition don’t quite work out as planned, there’s something endearing about the image of a hairy, snarling small-town vigilante staring down the forces of late capitalism—shades, maybe, of Tom Laughlin as Billy Jack, filtered through a noble cinematic lineage of suffering, self-divided lycanthropes…

There’s more common ground between Fessenden and [John] Sayles—another filmmaker long since taken for granted—than one might think. After all, the latter made his name (and shored up his Hollywood collateral) scripting Joe Dante’s marvelous (and again, politically astute) werewolf shocker The Howling…

… Like Sayles, Fessenden is a regionalist interested in the relationship between the individual and the community, and he’s attuned to the specifics—from commercial signage to gift-store trinkets—that keep his B-movie archetypes honest. More broadly speaking, what Fessenden shares with Sayles—and while we’re at it, his frequent collaborator and one-time protege Kelly Reichardt and fellow indie eminence grise Jim Jarmusch (who cast him as a sheriff in The Dead Don’t Die)—is a bruised-and-blistered metaphysics of failure, the secret handshake of lefty directors who’ve been around long enough to not place too much stock in the future.

… The fatalism of its final sequences has its own spectral intensity—and integrity. In the final moments, a mortally wounded Charley flashes back to the night he was first attacked, and Fessenden gives us the film’s most shiver-inducing image—a carefully prepared shot-reverse-shot with the architecture of a jump scare but a very different feeling underneath. Instead of shock—or surprise—the money shot conjures up a tender, heartbreaking mix of existential resignation and recognition: the only possible response for when we all find the wolf has suddenly and inevitably come to our door.

Add a comment