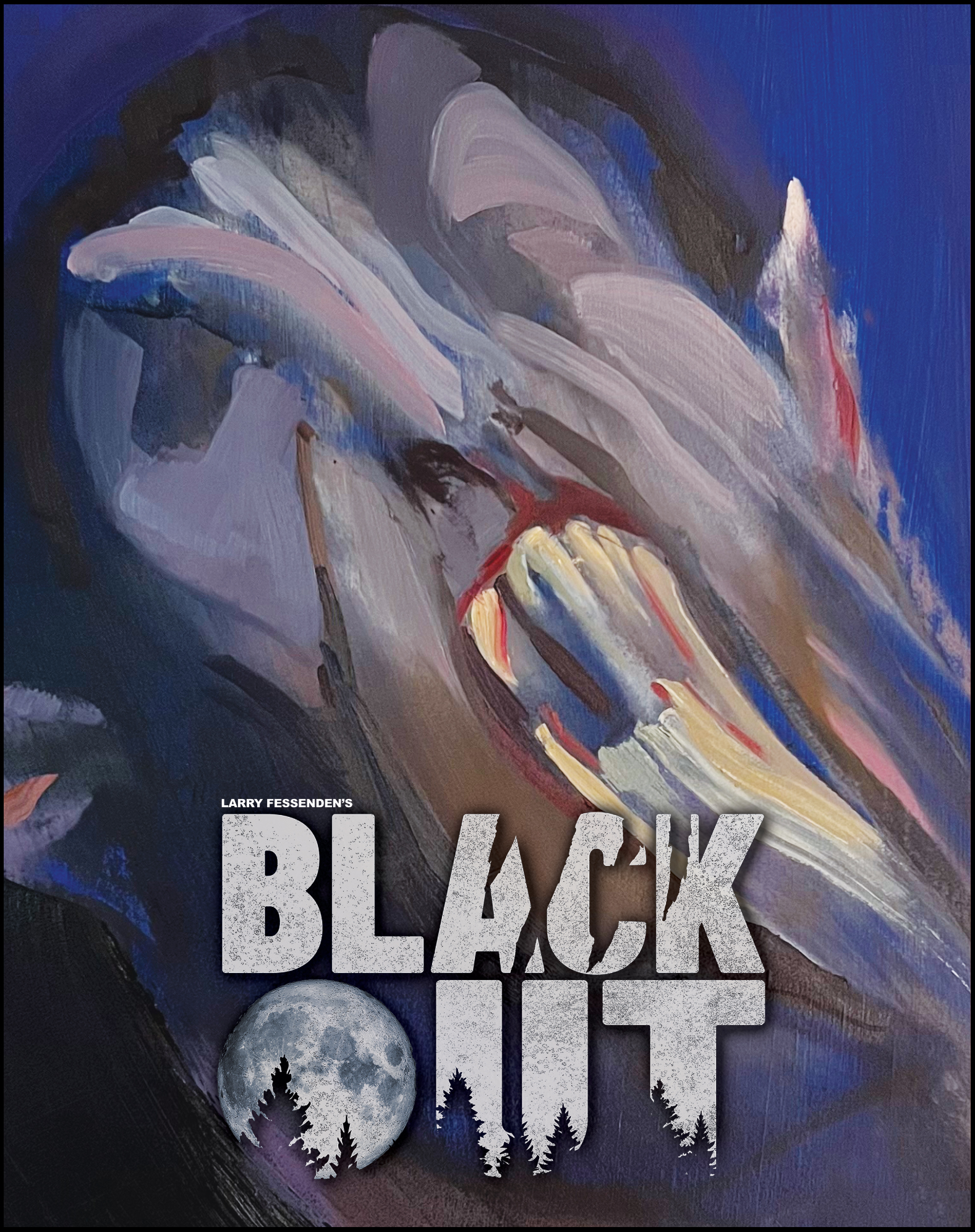

Director Larry Fessenden is no propagandist.

The cult horror filmmaker stressed that point when talking about The Last Winter, his 2006 work, set at an arctic oil outpost that nature sees fit to eliminate along with the rest of humanity. The topic of oil drilling, an obstacle to the United Nations Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 13 on Climate Action, angers Fessenden and is an issue he approaches out of personal frustration, not a call to action. That shouldn’t mean it’s any less important.

Fessenden may not be a name outside the horror genre, but audiences likely recognize him from his 114 acting credits and the BAFTA-award-winning role-playing game he wrote with Graham Reznick, Until Dawn. Ironically, Fessenden never plays video games himself.

The following interview with Larry Fessenden covers not only the artistic creation of his film, The Last Winter, but the horrors behind the story of climate degradation and current culture wars that may distract us from working together.

What is the scariest thing in the world to you right now?

Obviously, it’s climate change. And another thing that’s scary is that we’ve proved, at least in America, that we no longer believe in cooperation and getting along to solve problems. We’ve spiralled into a narcissistic death spiral of tribalism and I think stems from the commercialization of capitalism leading to identity obsession.

This all came from the power of commercials. After the 60s, people realized they could sell their sense of identity so you’d start to become more and more oriented with the products that you bought – they became your identity.

And I’m speaking very generally to your question because I think this is a trend in human history that has happened for the last century and has led us to an intractable ability to solve problems together and there’s no greater problem than climate change.

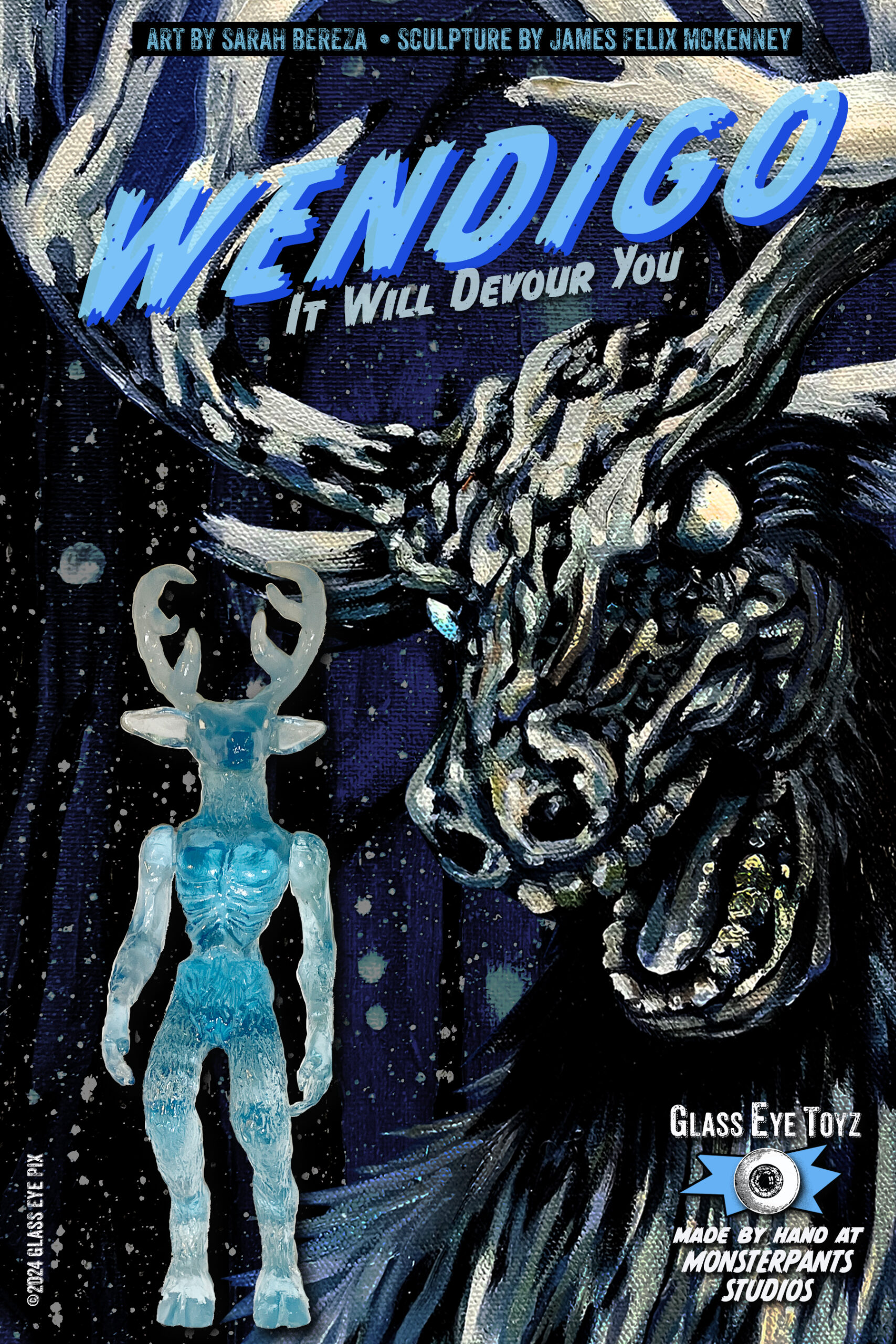

Before we go into that film, The Last Winter, the Wendigo (a mythical evil creature in Native American beliefs) is not something that’s very common in popular culture. Why do you feel it’s an important creature of myth?

One thing I love about the Wendigo is that it is, in fact, somewhat undefinable. It, of course, originates in the Ojibwe mythology and it was, as I understand it, designed to be a cautionary tale about overreach. Specifically, if you’re caught in the wilderness with your fellow travellers you don’t attack them and consume them.

So it’s associated with cannibalism, but I think it works also as a metaphor for manifest destiny. So I’ve used it both as an intimate cautionary tale and then with bigger implications, that’s why I like it.

Also, it’s not clear how it’s depicted because it’s mythology. Not like our Western monsters where there’s an origin book – Frankenstein’s a book – so you riff on that. Whereas because the mythology of the Wendigo is so much more unknowable and unattainable, it’s that much more rich and wonderful.

What comes first when you’re developing an idea – the monster or the story?

Well, they’re inextricably linked because the way I think of things is in terms of themes and the implications. Even in speaking of a monster, the question is what is the essence of a monster, what makes the story enduring?

Why do we care about Godzilla? Well, first, it was a response to the atomic bomb and the usual sort of cautionary tale about if we play with atoms we’re going to end up with things that are out of our control. As such, Godzilla seems to be more about nature.

The character itself even has personality quirks; sometimes he’s bad, sometimes he’s good. So, you can spend all your time deciding whether he has gills or not, but you really ultimately have to deal with the themes that the monster represents.

Once you’ve decided that you’re focusing on a particular creature with particular themes, what dictates what makes it scary? You’ve used multiple approaches with the Wendigo.

Ironically the sad part of my life is that I don’t know that my movies are very scary. [Laughs]. Which is why I’m not a very popular filmmaker. I feel there’s a sense of dread in all my films, and, in a way to me, the essence of horror is unknowable dread. A lot of the themes in my movies are about self-betrayal.

In The Last Winter, it’s a self-betrayal on a societal level. How we let our disagreements – personal disagreements – overwhelm our ability to use humankind’s great resource, which is reason and communication. To toss those aside is another self-betrayal.

And then I made a movie which was disliked for reasons I don’t fully understand called Beneath which is about a bunch of kids in a rowboat with a monster in the water. The thing is, they can work together and get to shore – it’s only like 20 feet away! But instead, they argue and come up with stupid solutions that are counter-productive and actually quite vicious.

In my mind, that’s where we are politically. Instead of trying to solve problems, we’re figuring out more and more nasty ways to combat each other. That’s why I liked that film, I’m not here to apologize for it but I’m not sure why people don’t respond to that because I think it’s as biting as anything I’ve done.

It’s not your job or horror’s job, but what insights do you feel the genre has to offer in the problems we’re facing today?

I think the most relevant answer to that question is simply that, while being in entertainment, we can discuss issues that are important. But also, I don’t sit down and say, “Let’s see, what’s the issue of the day?”

I’m not a propagandist. The fact that I am saddened by something like climate change is actually much more of a personal thing where I feel that sense of self-betrayal in the same way that it does relate to alcoholism and things that are much more personal to me but also to other people.

I always reject the idea that you can’t have a story with a message. It’s funny, you know, if you make a cop movie – cops and robbers or murder and a detective – no one is saying, “You’re making films about justice, what kind of preposterous, pompous, person are you?” No, it’s in the guise of justice that I’m telling a cool story about a gumshoe who’s solving problems.

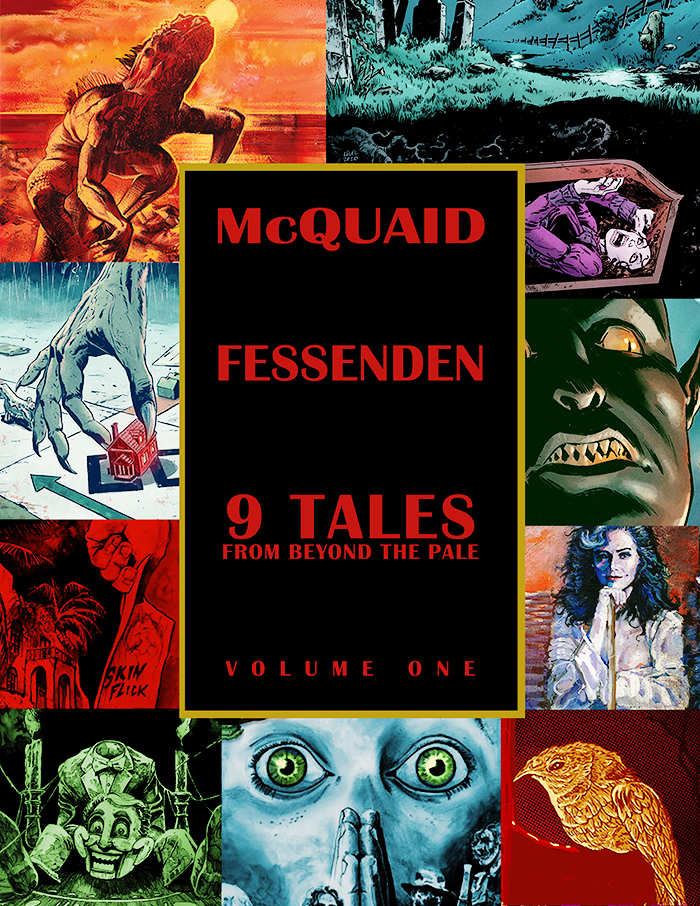

So if I have a horror film where clearly the theme is Frankenstein’s monster was brought into the world and then abandoned by his parents [Depraved], yes, it’s a movie about parenthood – but it’s also about Frankenstein which is cool! So there’s an aesthetic aspect to genre filmmaking that’s completely about the colours, the mood, the music, etc..

The greatest emotion that I feel is this sense of awe and existential bewilderment that we’re alive and then eventually we’re not alive. That all seems crazy, that you can die slowly from cancer or quickly from an axe in the head, that all seems like great stuff to make movies about.

So the idea is that entertainment is still the agenda, but not pandering entertainment that’s designed to make money; entertainment that’s designed to draw you into an individual voice, which is what a filmmaker is. Obviously, a painter is too but a filmmaker is also a singular voice and the fact that it’s a hugely collaborative medium doesn’t take away from that.

The Last Winter is a film I can see certain people having issues with. How hard is it to get something financed that’s both horror and politically charged?

It’s impossible. I can’t do it anymore. I couldn’t do it with Depraved. I had meetings for seven years about my Frankenstein story. I mean, I could have pitched it harder, it’s not a particularly political movie, but it is about society in crisis which – I thought it was in crisis then, you can imagine what I think now. [At the moment] people don’t want to finance all of my films.

If you were smarter than me or a better showman you could go in there and emphasize other elements in the meetings. I certainly did that, I said, “My Frankenstein will be sexy,” I had a lot of ideas. But in the end, I’m talking about a war veteran with PTSD during the Iraq crisis and it’s obvious I have other things on my mind than just getting the kids into theatres. It’s also a trick with timing. I always feel that if I got Habit into Sundance back in the 90s, I would have been given a little bit more mojo and it would have altered my career.

In the end, what I always talk about in showbiz is that everything from your reviews to the distribution model is about power, not to soak your ego but to continue to do the work that matters to you.

How do you feel about how media is consumed today – in this less precious fashion?

I am extremely resistant. I’m just a product of my time. I don’t even like television series, or at least I resent them, because they demand so much of my time. I prefer the 90-minute, two-hour format. I’m not quite as fetishizing about going to theatres because I have a very big television.

I believe it’s such a lost art. I grew up in New York City and I would go to the theatres to see double bills. That’s really where I saw all the 70s movies, Little Big Man or the Hitchcock movies in the 80s. At the Thalia theatre uptown, there was Cinema 80 where I saw Citizen Kane – rear-projection. Now, the kids are watching content on their phones, and apparently, they don’t really watch movies, they’re watching TikTok.

The thing about the 90-minute movie is that it’s about empathy because you’re watching someone else’s point of view. Even if the characters don’t do what you want, you’re trying to understand, and so I believe that’s a very wholesome experience.

Whereas if you’re playing video games, you’re primarily preoccupied with what you want to do which is what you do all day long anyway. Making choices to perhaps benefit yourself. I’d be fine to have an argument with someone who would school me and correct me but when they say they’re replacing movies, I get antsy.

However, you did write a video game! How was that experience compared to screenwriting?

I did indeed. I wrote it with Graham Reznick and was invited in because I was sort of a Wendigo expert. Also, because I don’t play video games, I invited Graham to participate in writing the spec script and we got the gig.

We had the best time because we loved our bosses, Supermassive Games, and they really were committed to doing something very special and unique. And, in a way, we were tasked with writing not one but 25 movies because of all the branching.

It’s really almost like just exposing the writing experience. Because, you’re thinking, “What if Henry, goes off the scene and falls off the cliff?” Well, we have to write it. “What if Mary has an affair with Louie?” And then you have to write that too.

It’s important to understand that Graham and I did not come up with the story. We were sort of the architects of the characters and then Supermassive would say, “We want these things to happen” and we had to make it psychologically realistic. That’s why I had such a good time doing it; it was almost this Choose-Your-Own-Adventure style.

For more on Fessenden’s work as an actor and filmmaker, visit glasseypix.com. For more on how to combat climate change, visit here.

Add a comment