There are certain generally held expectations about the relationship between reality as we live it every day and films set in a dystopian future. No one who has watched even a few minutes of cable news in the last decade or so could doubt that contemporary American life, in some ineffable and undeniable way, currently exists within one or more Paul Verhoeven films. But while the broad strokes generally rhyme, some crucial details don’t quite match up. The hearty tonal psychosis, relentless soul-deadening violence, and amorphously horny militarism are very much in place, but contemporary life still lags behind the Verhoevenverse in terms of extremely ambitious lapels on men’s suits, routine space travel, and robotic cop technology. Natural as it is to envy the efficient transit system of Cohaagen’s Mars or even just wish for a little more Renee Soutendijk in the monitors, this is generally good news.

There is one notable exception to the usual reality-to-dystopia ratio, though, that is both humbler and infinitely more unsettling. On September 11, 2006, Larry Fessenden’s The Last Winter premiered at the Toronto International Film Festival. The film was the most ambitious and expansive of the independent horror auteur’s career, and a long time in the making. Fessenden started writing the film in November of 2001; producer Jeff Levy-Hinte began shopping the script, on which Fessenden collaborated with the writer Robert Leaver, in 2003. It was a horror movie, but more specifically it was a Larry Fessenden Horror Movie, which is to say a doomy character-driven mood piece, with the dominant mood being Choking Dread. Also, it was about climate change, and set at a remote oil company outpost in Alaska’s Arctic National Wildlife Reserve where debates about the ethics of natural resource exploitation give way to something darker. It was not going to be an easy sale, in other words, and it did not sell. Levy-Hinte struck out with the larger independent studios.

“Every one of them said the movie would be a ‘tweeny,’” Fessenden told Indiewire in 2007, “in between genres—not horror, not drama—and passed.” The film was eventually financed with a grab-bag of private funding; after scouting locations in Alaska and Canada, Fessenden wound up shooting most of the film in Iceland, with the Icelandic Film Commission coming on as a co-producer. The production started in March of 2005, and the conditions during the three-week shoot mirrored the chaos in the film—“in subzero temperatures, or in un-seasonal rain, or winds of 40 knots, or blizzards, or a blistering sun,” Fessenden wrote in August of 2006. “Iceland is experiencing acutely the radical temperature shifts from global warming even today, and many of the outlandish scenarios in the script were actually occurring.” Fessenden immediately re-cut the film after its TIFF premiere; months later, IFC beat out a few competitors for the rights to it. “There was no bidding war,” Fessenden told Indiewire.

The Last Winter opened in a limited theatrical/streaming release in late September of 2007 and grossed less than a hundred thousand dollars worldwide. It’s perhaps the fullest realization to date of That Larry Fessenden Feeling, which connects an astute and engaged social consciousness with a certain freewheeling reverence for horror’s foundational myths. But, more to the point, The Last Winter holds a bleak record for dystopian films given how quickly its central conceit went from disturbing speculative fiction—literally the stuff of a horror film, albeit a low-key and dread-intensive independent one—to an observable, scientifically quantified fact. The Last Winter posited the melting of the Alaskan permafrost as an opening onto the end of everything else when it opened in six theaters in September of 2007. It was a little less than a decade before reality caught all the way up—to the first part, at least.

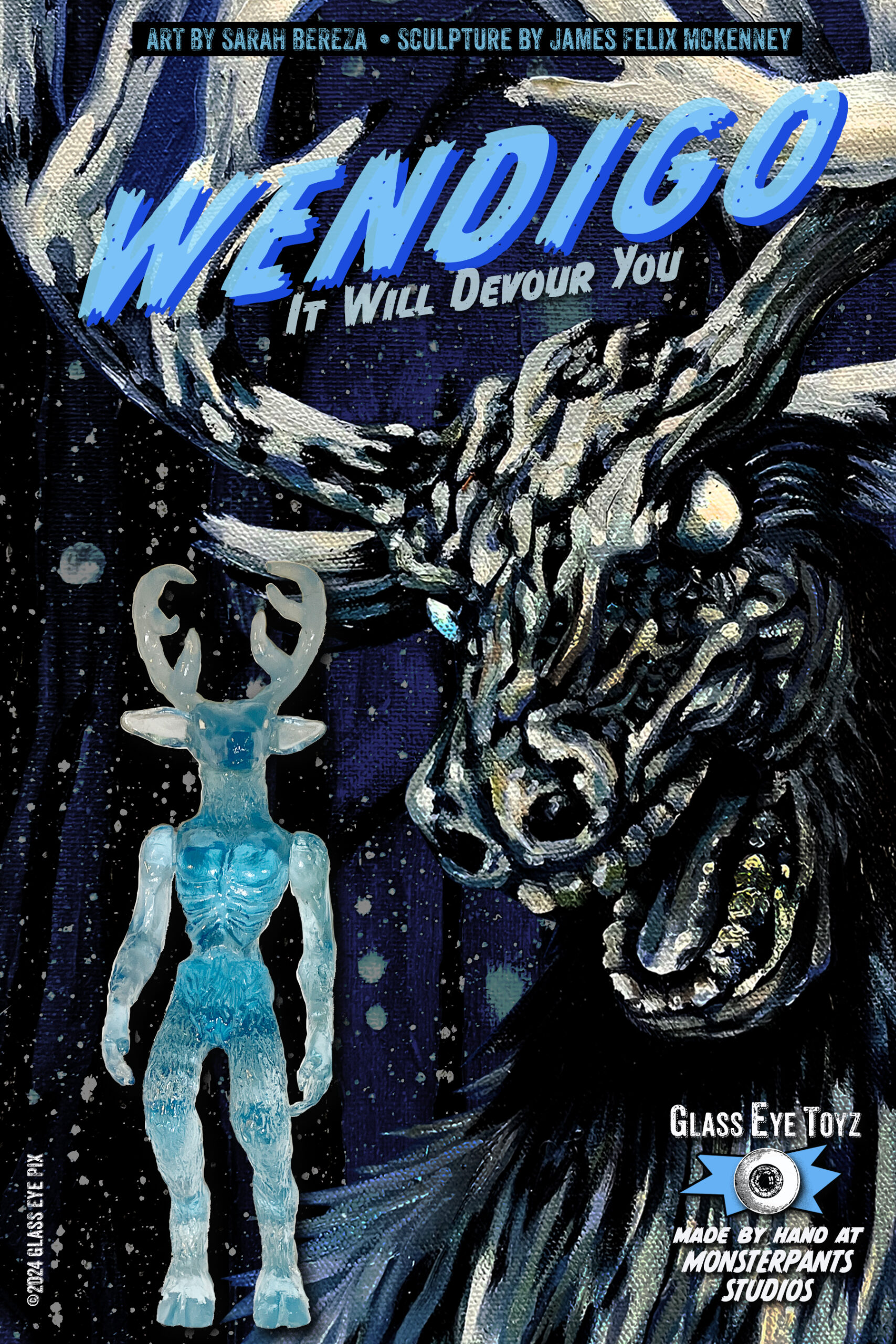

This is probably a good point to mention that the movie happens to be very good. It is indeed a “tweeny,” but that is the valuable and shrinking genre space in which Fessenden does what he does. He’s a horror movie director more or less by default, but he also seems to come by it naturally—in making a movie about the loss of self that comes with addiction, say, or the immutable and intractable aspects of class conflict, Fessenden wound up making an ace low-budget vampire movie (1995’s Habit) and a multiply haunted werewolf fable (2001’s Wendigo) that are all the more effective because of how discomfitingly comfortably the subject and fable fit together. This is a strange and difficult thing to pull off, but the connection between urgent, human-scale conflict and the broader mythic concerns never feels forced. Fessenden’s films are strangely and stubbornly themselves; it is as if only myth can quite explain the familiar and variously fraught real world borders along which his films are set.

All of this would seem to set Fessenden up as the ideal director for a horror movie about a topic that, for all its reeling apocalyptic sweep, is generally lived in the present through a series of picayune partisan skirmishes. The question is whether such a movie could in fact be made, and why there have been so few attempts. The most obvious reason why there have not been any good, scary movies about climate change also happens to be the most compelling: it’s just too fucking scary. The bigger studio features that have taken on the topic have been goofy both because they are bad, and because a less-goofy approach would make them something significantly darker than a big studio feature should be. Roland Emmerich’s The Day After Tomorrow (2004) envisions climate change as a series of suspiciously gray-looking CGI effects conspiring to keep Dennis Quaid from reuniting with his son; at one point, Jake Gyllenhaal literally outruns an ice age and escapes it by slamming a heavy wooden door against a freezing polar wind. M. Night Shyamalan’s The Happening (2008), in which the world’s plants pursue a merciless allergy-inspired revenge against the human race, is more understated by default, but also exponentially dorkier and somehow even less frightening.

Neither of those filmmakers are ever going to make the signature film about any topic, but the twinned and overdetermined dippiness of those misbegotten epics helps explain both why The Last Winter works as well as it does and why so few films have taken up this particular challenge. In a formal sense, horror movies need rules; when those rules work, you’re both afraid enough in the moment and invested enough in the film’s internal logic not to be bothered by the idea that some towering and ravenous evil can be banished—or fought at least to a sequel-ready standstill—by deftly deployed Catholic kitsch or half-scientific gimcrackery or some bespoke incantation. Even in the most effectively dreamlike horror films, basic narrative structure matters, if only so the person watching knows what’s happening enough to know what to be afraid of.

Global warming just doesn’t work like that, as a film villain or in any other way. There are a number of reasons why even thoughtful people might recoil from thinking about what global warming is doing and will do to us. The vastness and implacability of it, the sense that the ship has in some meaningful sense already sailed, the dreadfulness of what we know and the formless and more dreadful prospect of what we don’t, the pure and prosaic horror of an annihilating force so much greater than us—these are scary, but this is the sort of fear that people go to the movies to avoid thinking about. Fessenden does not shy away from any of that, but this is why he is Larry Fessenden and, say, Roland Emmerich is not. It probably also has something to do with why The Day After Tomorrow made $544 million in domestic box office receipts and The Last Winter…did not.

Reviews, if you are curious, were generally very positive. The AV Club respected the craft, but thought The Last Winter was didactic to the point of bloodlessness, but Manohla Dargis evoked Val Lewton while giving the film something like a rave in the New York Times and John Anderson wrote in Film Comment that Fessenden “found something profoundly, metaphysically scary within the facts and figures of global warming.” Even Variety liked it, while noting that it will “fare best in ancillary [markets].” The Last Winter opened in just six theaters in the United States, although IFC also made it one of the earliest films available for day-and-date streaming. It didn’t make a lot of money anywhere—Box Office Mojo has its total lifetime gross at $97,522, with nearly two thirds of that coming from overseas—but it was added to the permanent collection of the Museum of Modern Art. The Last Winter is, in short, just the sort of smart, scrappy, distinctive, deserving movie that disappears a few dozen times every year. It just somehow happens also to be the only good genre movie about climate change that has been made during the decades in which that phenomenon has shaped and threatened life on earth.

It is one thing to buy a ticket in order to be scared; it is another thing entirely to face down prosaic, literal, merciless and mirthless doom. The Babadook is a lot easier to face—and, not coincidentally, to visualize on a budget—than the horror that Fessenden puts forward in The Last Winter. “What if the very thing we were here to pull out of the ground were to rise out of the ground willingly and confront us?” James LeGros’ journalist-turned-environmental-consultant writes in his journal. “What would that look like?”

Visually, The Last Winter veers effectively between claustrophobic and unsettlingly horizonless. The Icelandic cinematographer G. Magni Ágústsson is precise with with the seasick institutional greens and smudgy whites and murky brown foods and general crushing linoleum vibe of the outpost’s interiors and disorientingly vast everywhere else, with exteriors defined by blanking expanses of shocking white and blue. The former replicates the bleak shitscape of grim paneling and frozen fluorescence that Fessenden and Levy-Hinte observed during their location scouting in Alaska’s Prudhoe Bay; the latter is Iceland, playing itself. Jeff Grace’s musical score is lyrical where it intrudes, but there isn’t much of it; there is a great deal more of Anton Sanko’s (separately credited) ambient score, which is felt mostly through recursive tones and atonal gestures and the insistent sounds of wind and wings.

A killer cast grounds the film even as it becomes more digressive and hallucinatory. Ron Perlman swaggers and booms and sports a jaunty earring as an oil company factotum forced to confront the end of a business model that has plainly shaped his worldview, but allows enough doubt to suffuse his performance to keep him human; the script is not necessarily subtle and hardly ever lets Perlman be anything but wrong, but he’s not a villain or even a fool so much as another helpless person caught well out over his skis. LeGros makes for a low-key counterpoint to Perlman’s brashness, but his intelligence registers strongly enough throughout that the character gains authority as everything around him frays. The plot sets Connie Britton’s Abby up as a point of romantic contention between the two, but because the character is played by Connie Britton she emerges as significantly more than that—smarter than just about anyone else in the film, and savvy enough to know it and not to give it away. Her Friday Night Lights cast-mate Zach Gilford has a smaller but more pivotal part, and is exactly as haunted as he needs to be. Dillon Panthers completists will be happy to know that Gilford plays football during a drunken game of two-hand touch at the outpost, albeit in more of a scatback role than the game-managing quarterback one that he was playing alongside Britton on Friday Night Lights at the time. (For fantasy football players: Britton also scores during that game, on a rather incongruously well-designed screen play.)

How scary this all is depends on what you look for in your Being Scared experience. The back half of the film delivers some effective conventional shocks, aided to various degrees by some fairly literal CGI effects, but the first half establishes just how good Fessenden is at the strange thing that he does. As in the best moments of Wendigo, the anxieties inherent in his chosen themes—not just the classical tropes he played with in the trilogy that established him as a sort of oddball horror auteur, but the ones having to do with the societal and human conflicts closer to the heart of the story—enhance the effectiveness of what his budgetary constraints and what is either a contingent or inherent tendency towards understatement allow him to deliver. Given the topic and given the particular story he tells, the approach works. “Something up here’s off,” LeGros’ Hoffman writes in his diary. “It’s in the numbers but also… you can feel it.”

Fessenden focuses on making it felt. The ominousness gathers to the point where small things arrive with something approaching the assertiveness of a jump scare; a sudden squall of arctic rain, the incongruous pop of a blaze orange rescue sled bouncing behind an outbound snowmobile. The back half of the movie, in which various systems and failsafes and people fail and fail and fail consecutively, takes on an increasingly dreamlike gravity. That’s the scarier part. I don’t imagine it qualifies as much of a spoiler to learn that not everyone makes it out okay.

It’s difficult to say that any one idiocy plucked from the roaring confluence of cynicism and obfuscation and plain self-thwarting bad faith that defines the contemporary American conversation over global warming stands out as more idiotic or worse than any other one; every willfully wrong thing is knotted up with and contingent upon a half-dozen others. The situation wasn’t much better in the years when Fessenden began working on The Last Winter, although there is a sense that in this area as elsewhere, something has gone luridly wrong in the last few years.

Where there was once a wary and heavily qualified consensus over global warming supporting the usual circular partisan palaver—something is happening, to be addressed by some kludge-y compromise between people concerned about the problem and other people more concerned about the impact of the solution—there isn’t really, anymore. The word “polarizing” doesn’t seem sufficient in a world whose geographic poles are currently warming twice as fast as the rest of the earth and regularly calving away into the ocean, and anyway the conversation over global warming hasn’t so much polarized as it has metastasized. In the domestic politics of 2017, global warming has become a partisan issue like any other, discussed in increasingly parallel languages that reflect deliriously different engagements with the issue. Where once there were two differently insufficient approaches to the problem to reconcile, we have receded into abstraction—the debate, now, is mostly about each side’s problem with the people on the other.

We would not be here without innumerable tragic and cowardly misapprehensions, but there is one thing that stands out, in The Last Winter and in general. In Hoffman’s increasingly dark and despairing journal, he writes “the biosphere turned, become unfamiliar and erratic. I would say vengeful, but nature is indifferent to us. We fight for our survival, not nature’s.” The character is ranting and increasingly at the end of his tether—he contradicts himself, in the same doomy register, in the very next sentence—but there is something here that Fessenden clearly both understands and wishes to make understood. There is a point at which the question of conservation turns away from nature and towards something more immediately self-interested and urgent. It is disheartening in the extreme that, as we find ourselves in the moment of confronting the existential challenge under the old abstractions, the broader conversation has retreated into know-nothing denial and wimpy-willful sophistry.

It’s a commonplace of discussions on the it-actually-exists-and-is-bad side of the global warming debate to opine that better storytelling is needed. This is the side of the debate on which virtually all of the scientific facts and elite consensus reside, but that consensus routinely expresses itself in the washed-out language of scientists trying to speak English; the facts, factual though they may be, are so crushing in what they promise that they become abstract again. It is natural to turn away from horror at that obliterating scale. It is a difficult story to tell because it is one humans are seemingly built not to understand.

In The Last Winter, Fessenden chose to tell it anyway, and much of what is most powerful and most powerfully unsettling in his movie owes to that. He literalizes where he has to in order to make the story work, and he caricatures where he must to make the points he wants to make; this is his job. But his first decision was his bravest, and it would make The Last Winter stand out even if more—any, really—films had similarly risen to this challenge in the decade since. Plenty of horror filmmakers have wrestled with monsters. Fessenden took on one that he knew he couldn’t beat.

Add a comment