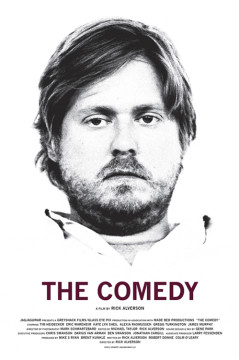

The Comedy

Dir. Rick Alverson (2012 94 min, alexa, 16:9, )

Tim Heidecker, Eric Wareheim

On the cusp of inheriting his father’s estate, Swanson is a man with unlimited options… As Swanson grows restless of the safety a sheltered life offers him, he tests the limits of acceptable behavior, pushing the envelope in every way he can.

A.V. CLUB

Rick Alverson November 8, 2012

“Williamsburg represent,” Tim Heidecker halfheartedly declares to a bar full of African-American patrons in The Comedy. “Represent what?” one of them replies. And there, in a nutshell, lies the thesis of Rick Alverson’s prickly examination/example of disaffected Brooklyn hipsterdom, and the towering fortress of irony and cock jokes that wall up access to the soul—if one even exists anymore. Like an arted-up twist on provocative anti-comedies like Lars von Trier’s The Idiots or Tom Green’s Freddie Got Fingered, The Comedyis deliberately off-putting, offering a hero who wallows in booze and entitlement, and gets thin pleasure from needling people by defending Hitler (“if you take murder out of the equation…”) or slipping into the voice of a Southern plantation owner. There’s genuine pain at the core of Heidecker’s character—or at least a numbness where the pain used to reside—but the film is keen on obscuring it.

An early scene sets the tone: Sitting morosely by a hospital bed, facing the certainty of his father’s death and the uncertainty of where his life will go afterward, Heidecker snacks on cookies and scotch, and peppers a male nurse with questions. Has he ever had to deal with a prolapsed anus, when the muscle gives out from abuse and hangs down in a tissue sac? Was he taught about that along with the women in nurse school? The formalities of Heidecker’s father’s considerable estate come up throughout The Comedy—and more subtly, the emotional fallout does too—but elsewhere, Heidecker talks nonsense with his buddies (including his Tim & Eric partner Eric Wareheim, Gregg Turkington a.k.a. Neil Hamburger, and LCD Soundsystem’s James Murphy) and provokes people for sport. Sometimes he’s actively trying to hurt somebody, other times he’s just pushing the limits, like an overgrown child.

The Comedy harshly assesses a particular breed of drifting, decadent, trust-funded Brooklyn layabout, but not from a safe distance—it implicates itself, and feels more like an act of raw self-loathing than cool portraiture. Heidecker’s performance is absolutely pitiless, inviting no sympathy, yet suggesting some faint embers of humanity under the surface, some private agony that cannot be salved by his relationship to other human beings. It’s a nasty piece of work, to be sure—John Waters once considered audience members vomiting during his movies to be like a standing ovation, and that seems to apply here—but it’s melancholy as well as abrasive, with a moody tone that buffs out some of the in-your-face obnoxiousness and cruelty. Its audience may be self-selective in the extreme, but few films have better articulated the limits of irony as a force field against the world.

INDIEWIRE

Christopher Bell November 8, 2012

“Tim and Eric’s Billion Dollar Movie” and Rick Alverson’s “The Comedy” (starring Tim Heidecker) both played at the Sundance Film Festival, and it’d be easy to simply peg the former as your standard bizarre T&E affair and the latter as a dramatic arthouse effort. But that’s simply much too reductive for Alverson’s current character study, a film uniquely weird in its own right and filled with enough of the duo’s humor to make their followers happy — to a point. The director uses comedy to explore a man’s inability to be a human being as he constantly involves himself in situations purely for irony’s sake, refusing to take others’ lives into consideration. There was much, much talk about how unlikable Charlize Theron was in “Young Adult,” but as far as this writer’s concerned, she has nothing on Heidecker’s Swanson. It’s a difficult film in that sense, one that incites laughter but immediately questions the intent (and point) of the characters’ catalytic behavior. Occasionally feeling like the work of John Cassavetes, a la “A Woman Under the Influence” (not to put anyone off — the Cassavetes comparison has been so abused in the past few years by American directors that it apparently only means filming people talking), Alverson’s latest may be be a tough sit given its subject and attitude, but his expert hand and intelligent nature creates a worthwhile, singular experience.

As his wealthy father lay in an unresponsive state within their lavish home, Swanson ignores the reality of the situation by wasting the days hanging out with the likes of Eric Warheim and James Murphy (LCD Soundsystem himself). The nurturing atmosphere is Williamsburg, a Brooklyn neighborhood comprised of different ethnic groups but mostly consisting of your run-of-the-mill, butt-of-the-joke hipster culture. Swanson and his buds waste the days by playing wiffle ball, riding bikes, harassing a cabby that refuses to put on hip-hop music, and acting like mental patients at house parties. By himself, our protagonist’s motives are more mysterious — at one point, he comes upon a few immigrant landscapers and immediately inserts himself into the work, removing his shirt to get down ‘n dirty. When the homeowner swings by, Heidecker pretends to be the boss, confessing that his men continuously talk about the nearby pool and uncomfortably insists that they be allowed to take a dip. The estate’s owner agrees without much of a fight, causing Swanson to immediately drop the act and leave. This strange action begets a pattern, from pretending to be a sales rep at a furniture flea market to actually getting a low-paying gig as a dishwasher in one of the thousand eateries in Brooklyn. Part of it is the character hoping to get a rise out of people, failing, and briefly realizing his futile act — but it also charts his slow, admittedly resistant progression towards some sort of normal lifestyle. Cleaning an endless assortment of coffee mugs and dinner plates, Swanson is sarcastic when interacting with a waitress (Kate Lyn Sheil), but it still seems like his subconscious is trying to direct him onto the right path.

But the stern joker is unable to participate in anything earnestly, and as his father’s health deteriorates even further, his sister-in-law attempts to wrangle him into taking some sort of control of his life with the onset of their incoming inheritance. Alverson constantly assembles scenes with the potential for redemption but never forces his characters into it — the path is clearly visible but unfortunately not on the agenda for Swanson. In that sense things don’t wrap up neatly, there is no lesson learned nor is there at all a direct, sympathetic connection between the audience and Heidecker. Though the emotional attachment to our movie-leads is something we all automatically crave (hell, it’s been ingrained into us by cinema for decades), the director instead portrays a man long off the rails, where even the most pressing life circumstances fail to ignite any maturity. “The Comedy” is not a tale of morality, it’s a tragedy.

Alverson keeps the camera close, meticulously following all movement as if searching for a crack in the ego’s shell. When the director does frame wide, he captures the very small world of Williamsburg in all its youngster glory — going even wider, the Manhattan skyscrapers lurk overhead, the real world beckoning. Somehow, they’re able to ignore it. Combined with an eerie score, these moments are oddly startling and quite effective, conveying an enormous amount of feeling in a simple way. Heidecker is quite perfect for the role, obviously funny but also a very compelling lead, giving the film’s quieter moments an immense strength. His look not only suggests regret for his conduct, but also admits to a sort of weakness — can he really not handle these situations? Or is it that his desire to be an antagonistic clown greatly outweigh the urge to do the right thing? His crazier moments pull from Gena Rowlands rather than from the ballistics of his television program.

The film comes to a close with one last shot at Swanson’s redemption. As we look back on Alverson’s piercing critique of extended adolescence and rejection of obligation, one wonders why the hijinks of the characters were never met with any proper comeuppance, especially considering the amount of scenes in which Heidecker fucks with one or more people. A later scene involving a taxi driver involves some verbal retaliation, certainly something of substance, but it doesn’t exactly do the trick. What we draw from this moment is that his family considers him helpless and useless, while strangers don’t see him being worth any of the trouble. Fitting punishment, if a bit too subtle to be picked up on.

“The Comedy” sees the director working with bigger names but still retaining his sensibilities. We don’t have to mention that hipster culture is the new whipping boy (apparently we’re hipsters for liking Pixar) and Alverson could’ve easily fired at the surface, gathering plaudits for being topical. Instead he digs up something that affects more people than just Brooklynites, the lack of sincerity in our lives and this generation’s reluctance of commitment. It’s a meaty film, filled with ideas unobscured by any generic narrative string, a move that shows not only the confidence of the director but his respect of the audience. This is one that’ll have people talking.

FILM.COM

William Goss November 5, 2012

Tim Heidecker and Eric Wareheim have already unsurprisingly brought their cult favorite TV show to the big screen this year with the shrill, surreal “Tim & Eric’s Billion Dollar Movie,” but less expected is their involvement in Rick Alverson’s equally uncomfortable character study, “The Comedy.”

Despite the pasty revelry of its opening moments, this is more of a one-man show, with Heidecker taking the lead as Swanson, a layabout Williamsburg 30-something whose life is literally adrift on a yacht in the East River when he isn’t carousing with friends (including Wareheim and LCD Soundsystem frontman James Murphy) or confronting strangers. Swanson has a lot of free money, a lot of free time, an ailing father, an incarcerated brother, a fed-up sister-in-law and a primary interest in keeping the world at a jokey remove in his every social interaction.

Coming off as something like “Five Easy Pieces” for the hipster set, “The Comedy” reveals itself to be more of a tragedy about entitlement and self-loathing, a seemingly sincere movie about a deeply ironic and unfulfilled man as he belongs to a culture — hell, maybe even an entire generation — terrified of sincerity. (Even the film’s own title can be seen as an apt touch of irony at the expense of the “Tim & Eric” fanbase.) He pretends to work as a gardener to no avail before getting a job as a dishwasher that he doesn’t need. He harasses some cab drivers for not turning on the radio while bribing others to let him take the wheel for a night. He walks into a bar full of black men and casually offers to gentrify the place with the help of his own shades-and-shorts crew.

The only people with whom our beer-swilling, bile-spewing anti-hero would appear to get along are hospitalized strangers who can’t respond to his pranky presence at their bedside and kids who aren’t bothered by his insistence on always goofing around. When it comes to behaving around adults, though, Swanson doesn’t hesitate to forgo proper protocol and indulge in deadpan rants about the considerable merits of Hitler’s politics and the likely cleanliness of hobo genitals, a character trait that Heidecker sells without fail. “Billion Dollar Movie” sought to provoke by filling bathtubs with literal excrement; director/co-writer Alverson (“New Jerusalem”) is more prone to having Swanson fill conversations with it instead.

The film is in turn filled with conversations and confrontations like these as it meanders about, looking for trouble much as Swanson himself is, an aimlessness alleviated only by the slight promise of an oddball romance with an equally vulgar waitress (Kate Lyn Sheil). Like his lead, Alverson just wants people to care, even if that subsequent emotion takes on the form of hate, and as such, “The Comedy” has my begrudging respect.

“The Comedy” is currently available On Demand and will open in select cities starting November 9th.

THE NEW YORK POST

Kyle Smith November 16, 2012

Picture “Raging Bull” with a sleazy prep from the Brooklyn hipsteropolis of Williamsburg, and you’ll get the idea of “The Comedy,” a character study that tries to make the revolting compelling.

A fully committed Tim Heidecker plays Swanson, an entitled, rude, potbellied slacker who stands to inherit a massive fortune when his father, who is hospitalized and near death, slips away. In the meantime Swanson floats around on a boat in the East River, does some blue-collar slumming à la Jack Nicholson in “Five Easy Pieces” and harangues everyone near him with filthy monologues about whatever seems least appropriate at the moment. Here he is professing admiration for Hitler; there he goes telling a waitress he’s a convicted rapist.

Swinish as this character is, his gonzo alienation can be funny in the way of an outlaw comic as you await his next outrage against all decency. But Heidecker is no Nicholson, and the character lacks the magnetism of a true antihero. Moreover, the film’s hints that Swanson’s problem is mere sadness at the passing of Daddy seem facile.

THE VILLAGE VOICE

Karina Longworth November 7, 2012

Could there be a more unsympathetic character in today’s culture than a well-born white male who uses his privilege irresponsibly? A highly improvised fictional exposé in search of the elusive heart and soul of hipster nihilism, The Comedy stars alt-comic superstar Tim Heidecker as Swanson, a trust fund 35-year-old hanging out in Williamsburg, fucking around, and waiting for his sickly dad to die.

The title is ironic, or maybe “ironic”—the film, writer-director Rick Alverson‘s third feature, is basically a shock drama. Its sensibility is kind of a hybrid of the awkward conceptualism associated with Heidecker and co-star Eric Wareheim (TV’s Tim and Eric) and the brand of another of the film’s players, James Murphy, figurehead of blue chip hipster auto-criticsLCD Soundsystem. Where Murphy is known for dance tracks with lyrics that witheringly dismantle the pretensions of the audience most likely to dance to them, Alverson’s film takes the form of a kind of glacially paced, shaky-cam art project that the Brooklyn dude-bros it depicts might bike over the bridge to catch at IFC Center—if for no other reason than to tell chicks they’ve seen it.

Heidecker makes a much more convincing 21st-century Arthur than Russell Brand. Chubby, bearded, beer-soaked, bedecked in novelty sunglasses and shorts, Swanson lives on a boat—because he’s floating, get it?—and runs with a crew of dudes also defiantly unkempt. None of them are apparently married or seriously employed, and they have nothing better to do than to approach life as a starting point for a real-world version of improv comedy. Cab drivers are repeatedly fucked with. Swanson defends Hitler mid-flirtation, and the girl still goes home with him. The gang takes an ironic field trip to a church, followed by dive bar whiskeys. Swanson evolves from pretending to be part of a landscaping crew in order to mess with entitled homeowners to actually slumming it as a dishwasher; from blithely snacking on scotch and cookies while a male nurse attends to his sick dad to showing some glimmer of a desire to feel for the infirm.

Alverson has big ambitions: His statement in the film’s press notes describes his protagonists as “an inevitable byproduct of the utopian dream come to fruition, ignorant or oblivious to the precarious state of world affairs, the economic uncertainty of their own country and the stagnation of the culture in which they live.” I’m not sure if it’s a blessing or a failure that those ideas are barely gleanable from what’s actually on screen. There’s not a false note in the film, but maybe there’s a difference between accuracy and truth. Certainly you can’t accuse The Comedy of pandering to its audience, sentimentalizing its character study or even editorializing on top of it. That ultra-cool, matter-of-fact address is maybe the best way to speak to the knee-jerk indifference of its audience in this moment—the movie’s analysis of Swanson and friends’ behavior is essentially the cinematic equivalent of a Listicle Without Commentary on the Awl. But I wonder if decades from now, The Comedy might function as a sincere snapshot—its intended satire might be too dry, too implied, to survive the passage of time.

THE NEW YORKER

Richard Brody 2012

Tim Heidecker (of Tim and Eric) is front and center in Rick Alverson’s aptly titled movie, playing the role of Swanson, a hapless hipster—an idle thirty-five-year-old Brooklyn heir whose obscene wealth gives rise to obscene talk, attitudes, and behavior. The comedy in question is that of life itself—not just Swanson’s own but that of the friends, family, and unfortunate accessories to his singular existence, be it the male nurse who cares for his comatose father, the cabbie whose vehicle he wants to drive, or the woman who has a seizure on his yacht. This is, in effect, “Arthur” meets “Jackass”; Swanson attempts ever odder and uglier provocations to jolt himself from a permafrost ennui and enter something like real life, for which (as he discovers when he takes a job as a dishwasher) he’s utterly unprepared. Lurching through the city like Don Rickles on acid, he and his cronies spew a spectacular flow of id-riddled chatter and obliviously dish out harder knocks than those they go trawling for. The shock factor is tempered by the loopy pathos that Heidecker and Alverson find in the character; it’s hard to hate Swanson more than he hates himself.

VARIETY

Justin Chang

For a catalog of aggressively stupid, socially deviant male behavior, Rick Alverson’s cheekily titled “The Comedy” is not without a certain subversive intelligence. A dark, determinedly abrasive study of a slovenly Brooklyn hipster who spends his abundant free time harassing cab drivers, disrupting churches and assaulting everyone he meets with discomfiting sexual and racial language, this singular Sundance entry is certain to split reactions every which way; for some, the film’s critical view of its subject may not be enough to compensate for the displeasure of his company. Fans of star-comedian Tim Heidecker notwithstanding, post-fest commercial prospects look slight.

A memorably repulsive prologue depicts a bunch of guys carousing in and out of their underwear, sloshing their chubby, pasty-white bodies with beer. But this is no fraternity hazing ritual: Well into their 30s, these emotionally deadened man-child pranksters are overgrown in every sense, leading lives of such undeserved privilege that they can afford to regard the world with sniggering indifference to social niceties or human struggle. Masters of squirm-inducing comic cruelty, they perform for each other, for the unsuspecting strangers unfortunate enough to cross their path and, of course, for the viewer.

The film spends a plot-free 94 minutes following one of the men, Swanson (Heidecker), as he wanders around Williamsburg and other parts of New York, stirring up all manner of minor chaos. Addressing a nurse assigned to take care of his wealthy, bedridden father, Swanson delivers a badgering monologue about lower bodily functions. Getting into a political discussion with a girl (Alexia Rasmussen) at a party, he extols the virtues of feudalism and compliments Hitler. Somehow she winds up in bed with him on his houseboat, to which he brings the occasional date, ferrying her across the bay in his dinghy.

Some of Swanson’s stunts — such as when he poses as a gardener and asks a well-to-do couple if his Mexican buddies can swim in their pool — carry unsettling racial overtones, though they project not outright prejudice so much as an impish child’s unformed view of the world outside his bubble. Elsewhere, he and his friends get together for the equivalent of comedy writers’ roundtable sessions, holding extended mock conversations on inane and vulgar topics, and occasionally asserting their love for one another in voices tinged with sarcasm.

Given his surreally unhinged antics with funnyman partner Eric Wareheim (cast as one of Swanson’s bearded buddies) on their Comedy Central series or their concurrent Sundance premiere, “Tim and Eric’s Billion Dollar Movie,” Heidecker seems almost subdued here. Onscreen nearly every minute and often wearing thick-rimmed blue sunglasses, the thesp gives a compulsively fascinating performance replete with weird facial tics, vocal inflections and gestures. There are moments throughout, including the ambiguous final scene, that suggest Swanson is beginning to experience a flicker of empathy. But any confirmation of this is firmly withheld by the script (by Alverson, Robert Donne and Colm O’Leary), as are any telling details about Swanson’s background apart from his obviously wealthy family.

A level of monotony does creep in, and unreceptive viewers may well argue that to devote a feature-length movie to these sorry specimens of humanity, even in a harshly evaluative light, is to give them far too much credit. In scrutinizing so specific and pernicious a subsect of American culture, Alverson can hardly be said to be getting at universal truths, although some may well recognize, with a wince, the characters’ impulse to respond to the distant suffering of others with an insensitive one-liner. Pointedly, the focus is so entirely on the protagonist that one gets only the vaguest sense of his victims’ humiliation; scene by scene, the film sets up its joke and leaves it to us to recoil from the punchline — even, or perhaps especially, when it’s genuinely funny.

Alverson’s unfussy filmmaking breathes quiet assurance, as Mark Schwartzbard’s HD lensing and a deftly underplayed synth score (by Alverson and Champ Bennett) invite the viewer into a contemplative state. Mumblecore regular Kate Lyn Sheil has a brief, effective role as a waitress in whom Swanson might just have found his match, at one point taking their puerile performance art to an inexplicable extreme.

SLANT

Joseph Jon Lanthier November 4, 2012

The barrel-gutted, foul-mouthed protagonist of Rick Alverson’s The Comedy is Swanson (Tim Heidecker), a filthy rich man-child who spends most of his workless hours floating on a small yacht in New York Harbor. He makes occasional trips ashore to prank gleefully through Brooklyn’s most gentrified neighborhoods with aging friends (Eric Wareheim among them), or to imbibe malt liquor at his comatose father’s bedside, or to seduce hipster ingénues with his putatively racist and misogynist deadpan. One may wonder what more a porky thirtysomething could ask for. Yet Swanson has become so starved for mutually invested attention that he’s taken to hurling himself impishly through the world in search of emotional candor at any price.

No middle-class sanctuary escapes his pealing adolescence: He trades surreal dick jokes over brunch and sullies church pews with clownish tomfoolery. He delights in “touring” proletariat vocations such as gardening and cab-driving whenever the whim to do so strikes, then retreats back into safety of jerky needling after the gambits bore him. (He suspiciously infiltrates a posh backyard, for example, posing as a landscaper and begging untowardly for a swim in the stunned homeowner’s pool.) But from the get-go, this insolent kidding is understood as a ridiculously handicapped attempt at shattering social estrangement with insult and trickery, presumably so that any resultant raw nerves can be converted into a brief bond of sorts.

When his hideous routines fail to disarm their target audiences, Swanson is left begging for reactions before stoic faces. He launches butt joke after butt joke toward his father’s unamused male nurse, punctuating each with a request for acknowledgement: “Famous Anus Cookies…anything there?” Later, he stalls the discussion of sober family matters with his sister-in-law (Liza Kate) with a Southern-drawled bit about upholstering furniture with “slave penises and slave vagina.” “You know that was funny,” he pleads as she grimaces. And Swanson is funny, not only because of the frantic creativity behind his transgressions, but also because of his cockeyed commitment to negotiating attention with them. The abrasive gags he and his friends commit are less intended for self-amusement than for continual proof that they exist. However shameful it is to be uncomfortably dismissed by one’s peers, anger and rejection just barely qualify as human contact.

There’s little more to the movie than these increasingly existential antics, and yet Swanson’s angst undoubtedly appropriates the meta-narrative of choice for many American independent films of the last five years about post-graduate, pre-career adults—stories wherein disenchanted hipsters find a piece of themselves by pushing against the expectations of their environment. Swanson’s socioeconomic privilege is not unlike that of Lena Dunham’s wayward youths, and he confuses recklessness with growth as do the anxiously aging femmes in Miranda July’s The Future and Sarah Polley’s Take This Waltz. PBR cans and erstwhile LCD Soundsystem frontman James Murphy make mostly atmospheric cameos here as in Noah Baumbach’sGreenberg, which also portrayed gray-haired hip-sarcasm. The Comedy‘s painfully superficial male relationships furthermore recall those of Kelly’s Reichardt’s films, with the slow-mo, testicular groping of an opening beer wrestling sequence inverting Old Joy‘s frighteningly intimate boy-on-boy back massage. Both scenes imply that haptic closeness pays few emotional dividends between friends when their conversation remains mechanical and repetitive.

Swanson’s debt to other filmic traditions has been cited elsewhere: The New Yorker‘s Richard Brody pithily describes The Comedy as “Arthur meets Jackass,” a fair approximation of sketch-like moments wherein the character circumvents his stifling wealth by moonlighting as a dishwasher. The sense in which Swanson rubs up against the limitations of his counter-cultural zeitgeist, however, may link him more aggressively to Richard Lester’s Petulia. That movie explored the menacing side not only of social revolution circa 1968, which manifests itself as everything from promiscuity to playing a euphonium for the hell of it, but of the same era’s zany film-grammatical conventions as well. (Several dizzying party scenes and a shuffled timeline preclude comprehension of the basic plot.) Alverson and Heidecker similarly approach the various rings of hipster-dom hell with the intention of spoofing the milieu’s insularity and its compromised epiphanic potential. Is Miranda July’s human sculptural stretchy-shirt dance to a bombinating Beach House song in The Future any less self-indulgent than the way Swanson rents a bewildered cabbie’s taxi for 20 minutes, then abandons him with an angered pedestrian?

The title character of Petulia is a post-hippie who never quite experiences the swinging ’60s without the fear of male domination; Swanson is a post-hipster who never experiences irony without desire. And so the pampered, porcine prankster has awkwardly made irony an expression of his desire. Every scatological gag is an intimate strategy; every racist remark is a repressed need escaping him like a sour gas. And our emotional response to his behavior is, likewise, necessarily alloyed. Swanson does not amuse us in spite of the pity he inspires but because of it. Since laughter is one of the few forms of sympathy he can absorb, we can’t help but gratify him, even if its ultimate deliquescence implies ambiguous doom.

THE BOSTON GLOBE

Wesley Morris December 6, 2012

The movies’ long tradition of funny fat guys continues with “The Comedy,” except that its putative star, Tim Heidecker, is merely fattish and funny only to himself. But he struts with a waddle all the same, like a baby who’s mistaken himself for a man. Some version of both Heidecker’s assumed identity confusion and that tradition of tubby humor are under consideration in this movie, which Rick Alverson directed and co-wrote with Robert Donne and Colm O’Leary.

In the opening shot, Heidecker is drunk and partying with his buddies — including Eric Wareheim, Heidecker’s partner in sketch drollery; the comedian Gregg Turkington; and the musician James Murphy, who recently stopped being LCD Soundsystem. They jam their crotches into each other, but it’s not sexual because nothing about these men is sexual. It’s a moment that does indicate that Alverson wants to say something. An hour and a half later he hasn’t said it. The movie, which is set mostly in the Williamsburg neighborhood of Brooklyn, N.Y., is a critique of white-guy privilege, of Williamsburg’s hipsterism, of how men conduct themselves in comedies.

It operates in exactly the opposite way so-called bromances do. It’s as self-conscious as parts of “Knocked Up” and “21 Jump Street,” and as preoccupied with excretion and secretion as those movies’ peers. But it’s sucked dry of rambunctiousness. The jokes are desiccated, too. Alverson is working in a state of suspended irony. What’s he after is more specific than what hangs on the Judd Apatow family tree.

Heidecker leaves his family’s mansion, pads around the block, until he happens upon some men landscaping a yard. When the owners wander by, he says something to them in loose Spanish about his men wanting to use the pool. He’s assumed the role of the boss, and after one of the owners acquiesces to the pool, his work is done, and it’s off to the next stunt, unfashionable social position (feudalism could have really worked, Hitler actually did somegood, he argues), or harassment (“Why don’t you guys have satellite radio in these cabs,’’ he yells at one taxi driver). It’s off to drink near skeptical black strangers in a bar (“I’m trying to be honest with you, and you all up in my griiiiill”). It’s off to his boat.

The lonely provocateur Heidecker plays is named Swanson, which gets at the presumed ritziness Alverson is after. Swanson is 35, he takes menial jobs — or plays at them — because he can imagine nothing else for himself. He sits at the bedside of his (symbolically) dying father and mocks his male nurse. The closest Swanson comes to sexual affection is passively watching the woman he’s lured to his boat have a seizure.

Again, none of this is necessarily funny. That’s the extent of the irony here. Yet the film evokes so many comedians whose schticks would be peers of Swanson’s — Russell Brand, Zach Galifianakis, Seth Rogen, Jonah Hill, Nick Swardson, the men of so-called mumblecore movies and “Jackass,” Sacha Baron Cohen — and distills their lunacy all the way down to self-negating leisure-class dada.

There’s no filmmaking to enable the amusements the way Richard Lester’s did with the Beatles or Jean Luc-Godard’s can do with almost anything. “The Comedy” thrives on unalloyed contradiction: unfunny funniness, innocent guilt, self-conscious obliviousness, feel-good racism.

But what it doesn’t achieve is transcendence, the way, say, “Holy Motors,” Leos Carax’s current, similarly arbitrary adventure in personae, does. Lena Dunham’s “Girls” is another version of what Alverson is doing with “The Comedy.” The younger women on her HBO show are as self-obsessed as the men in this movie. But “Girls” is simultaneously funny and mortifying and true. It’s also guided by the distinct sensibility of a woman with a vision. Dunham perceives the assorted laws of the wider world and can mine comedy from the failure to both abide by and transgress them. Alverson might be thinking as big as Dunham is, but his movie feels smaller.

Swanson’s preoccupation with feces and semen befits a man whose life is as flaccid and constipated as his. At some point, he finds himself drifting around a swimming pool, and it’s tempting to think of Dustin Hoffman sinking to the bottom of the deep end in “The Graduate.” But there’s a difference. Swanson’s pool is empty.

SYNOPSIS

On the cusp of inheriting his father’s estate, Swanson (Tim Heidecker, “Tim & Eric Awesome Show, Great Job!”) is a man with unlimited options. An aging hipster in Brooklyn, he spends his days in aimless recreation with like-minded friends (“Tim & Eric” co-star Eric Wareheim, LCD Soundsystem frontman James Murphy and comedian Gregg Turkington a.k.a.“Neil Hamburger”) in games of comic irreverence and mock sincerity. As Swanson grows restless of the safety a sheltered life offers him, he tests the limits of acceptable behavior, pushing the envelope in every way he can. Heidecker’s deadpan delivery cleverly masks a deep desire for connection and sense in the modern world. The Comedy wears its name on its sleeve, but director Rick Alverson’s powerful and provocative character study touches a darkness behind the humor that resonates with viewers long after the story ends.

DIRECTOR’S STATEMENT

Each of my previous movies, The Builder (2010) and New Jerusalem (2011) scrutinized the utopianism at the root of American culture and the often great disconnect between people and their ideas. That disconnect is essential to my interest in movies – that gap between a perceived world and an actual material place. It provides me with both a general skepticism of the usefulness of cinema and a sense of it’s potential.

The Comedy takes that scrutiny of American culture, and its influence on global culture (under the promise of the free market), a step further. Much of the film was shot in and around Williamsburg and Greenpoint, Brooklyn. The first seemed indicative of a kind of progressive American exceptionalism, a bastion of the cultural elite, just past its prime and already in that strange state of monochromatic gentrification much like the group of privileged, aging hipsters at the center of the film. The second, Greenpoint, offered an intersection between immigrant culture and that young, burgeoning class of white, suburban ex-patriots. That collision of individuals for whom the American Dream has been achieved and become tepid, as dreams often do, and those for whom it is yet a form of sustenance, more emotional than physical, is a pivotal focus of the film. The group of men at the center of The Comedy seemed an inevitable byproduct of the utopian dream come to fruition, ignorant or oblivious to the precarious state of world affairs, the economic uncertainty of their own country and the stagnation of the culture in which they may live. They struck me as inherently sad characters, joyful in their bubble, as sympathetic as they are reprehensible, living in a progressively malignant social paradise where options and good fortune breed a desensitized indifference and recreational cruelty. They pacify their discontents with strange meta-mock sincerity and irreverence, as though humor itself were dying or dead and had nothing left to do but turn on itself.

Swanson, the protagonist, finds himself strangely at odds with the good life. We watch him take what may be the first decisive, yet idiosyncratic, steps in his privileged life–a strange flirtation with reality, a creative motion full of the ambiguous desire to be annihilated or embraced. With that action the film enters a voyeuristic arena, where both Swanson’s voyeurism and our own become, for me, the movie’s driving force. As opposed to engendering the protagonist with sympathetic attributes, my interest was to link the audience and the protagonist through their mutual desire for emotional animation and sensitization. For me the audience, the viewer, and Swanson are in the same predicament, are driven by the same conflicting set of desires. I am ultimately interested in the denial of those hopes, for the resolve of his annihilation (emotional or physical) or the satisfaction and relief of his salvation. I think that middle ground is the state in which we most often live and one from which the audience and Swanson both desire to flee, one that is denied its due in entertainment and even the grand drama of many of the arts. Ultimately there is a game at hand in the form of the film, an attempt to bait both Swanson and the audience into a reckoning with the muddy, nuanced, uneven ambiguity of life that is digested most wholly when the caches are cleared and the compartmentalization set aside.

Swanson’s inadvertent need for meaning as utility – for his hands and body to make sense in the world in a fundamental way, touches on the crisis of modernity. He has been divorced from that simple understanding, whether it be rosy or horrific, of a body’s sense in the world, of its literal use, both by his family’s good fortune and his country’s, in the way so many of us have lost that sense–divorced from labor, localism and basic intimacy.

ABOUT THE PRODUCTION

THE COMEDY brought director Rick Alverson, a Richmond native, to New York City. Production stretched over 25 locations in four out of the five boroughs, including a week of shooting on the water in and around the city. The “at sea” photography locales included the 79th Street Boat Basin, the Hudson and East Rivers and Greenpoint, Brooklyn’s disagreeable…Newtown Creek; a six person skeleton crew worked intimately on a 25ft sailboat, with a camera support boat chartered by an ex-NYPD detective.

On dry land the production maintained a key location hub in Greenpoint, Brooklyn (the cultural “South Beach of the Northeast”), which has become a hotbed for the filmmaking industry in New York, indie and studio films alike.

Environment was essential, since the narrative drive of the film is anti-hero Swanson’s increasingly desperate interactions with the people around him. Director of Photography, Mark Schwartzbard, utilized the Arri Alexa’s incredible latitude and efficiency to deliver striking imagery and speedy workflow in our naturalistic locations. But in order to properly bring that world to life on camera, the subjects who inhabit Swanson’s world needed to be authentic. This required a somewhat unconventional casting approach, which we referred to as our “Cassavettes style casting” – a nod to a master of using real-life environments and getting naturalistic performances.

In addition to traditional taped casting sessions; emphasis was made on hand-picked performers from the director and producers’ previous projects, casting directors hitting the streets with their camera phones searching for non-actors going about their every-day lives, and tapping in to word-of-mouth, like cast member (and non-actor) Jeffrey Jensen’s seemingly endless connections to the hipster enclave.

The film’s final cast saw an organic marriage between authentic New Yorkers and real-life musicians James Murphy (LCD Soundsystem), Will Sheff (Okkervil River), and Richard Swift (The Shins), as well as comedian Gregg Turkington (a.k.a. “Neil Hamburger”) and indie stalwarts Kate Lyn Sheil and Alexia Rasmussen.

In haste to make end of the year festival deadlines, during principal photography assistant editors downloaded and transcoded footage around the clock and Alverson’s editing partner Michael Taylor assembled the edit on a daily basis. Principal photography wrapped on August 25, 2011 at Alder Mansion in Yonkers, NY, seventeen shooting days after it began.

Tim Heidecker (Swanson) – As a freshman film student at Temple University he met Eric

Wareheim. After graduation they continued to work together on short films and strange bits of

comedic nonsense.

One of their first collaborative pieces was “Tom Goes to the Mayor” which made its way into

various film festivals. Fueled by Tom’s success Tim and Eric began sending their tapes to their

comedic heroes in Hollywood. One of those recipients was Bob Odenkirk who loved what he

saw and helped to develop their ideas into a TV show. Through a chance meeting Tim was able

to get their tapes to the senior vice president of Adult Swim, Mike Lazzo. He loved the stuff and

they were immediately given the funds for development. Tim and Eric used some of the money

to move to Hollywood where they worked on the show for a two season, 30 episode run.

Tim later went on to again collaborate with Eric Wareheim on their next show, the “Tim and Eric

Awesome Show, Great Job!” which aired five seasons on Cartoon Network. Tim and Eric also

created a spin off show starring John C. Reilly called “Check It Out! With Dr. Steve Brule” which

ran for two seasons. Eric has also collaborated with Tim on big budget commercials for brands

like Old Spice, Red Stripe, and Boost Mobile.

Most recently Tim completed his first feature film with Eric called TIM AND ERIC’S BILLION

DOLLAR MOVIE which was produced by Will Ferrell and Adam McKay.

James Murphy (Ben) – is an American musician, producer, DJ, and co-founder of record label

DFA Records. He is the front man of legendary musical project LCD Soundsystem, which in 2011

played their final shows to sold-out crowds at Madison Square Garden. In late 2009 Murphy

moved into film scoring and his initial project was writing music for Noah Baumbach’s film

GREENBERG.

Eric Wareheim (Van Arman) – Born and raised in Audobon, Pennsylvania. As a freshman

film student at Temple University he met Tim Heidecker. After graduation they continued to

work together on short films and strange bits of comedic nonsense.

One of their first pieces was “Tom Goes to the Mayor” which made its way into various film

festivals. Fueled by Tom’s success Tim and Eric began sending their tapes to their comedic

heroes in Hollywood. One of those recipients was Bob Odenkirk , who loved what he saw and

helped develop their ideas into a TV show. Through a chance meeting Eric was able to get their

tapes to the senior vice president of Adult Swim, Mike Lazzo. He loved the stuff and they were

immediately given the funds for development. Tim and Eric used some of the money to move to

Hollywood where they worked on the show for a two season, 30 episode run.

Eric later went on to again collaborate with Tim Heidecker on their next show, the “Tim and Eric

Awesome Show, Great Job!” which aired for five seasons on Cartoon Network. Tim and Eric also

created a spin off show starring John C. Reilly called “Check It Out! With Dr. Steve Brule” which

has ran for two seasons. Eric has also collaborated with Tim on big budget commercials for

brands like Old Spice, Red Stripe, and Boost Mobile.

During his free time Eric uses his passion for music to direct music videos. He has created videos

for MGMT, Depeche Mode, Major Lazer, Flying Lotus, HEALTH, Maroon 5 and more.

Kate Lyn Sheil (Waitress) – A graduate of NYU’s Tisch School of the Arts. In the years since,

she has gone on to act in such films as Carlo Mirabella-Davis’ KNIFE POINT, Alex Ross Perry’s THE

COLOR WHEEL (AFI 2011), Lawrence Michael Levine’s GABI ON THE ROOF IN JULY, Sophia

Takal’s GREEN (SXSW 2011), Joe Swanberg’s SILVER BULLETS (Berlin 2011), and Adam

Wingard’s YOU’RE NEXT (Toronto 2011). This year has continued to be busy with the completion

of Amy Seimetz’ SUN DON’T SHINE (SXSW 2012) and Robert Byington’s SOMEBODY UP THERE

LIKES ME (SXSW 2012). Kate was featured in the 2012 edition of the Nylon Young Hot Hollywood

Issue. She currently resides in Manhattan.

Alexia Rasmussen (Young Woman) –just finished shooting the independent KILIMANJARO,

starring opposite Brian Geraghty. She next shoots Zack Parker’s thriller PROXY opposite Joe

Swanberg. Her first job out of NYU was playing Cybil Shepherd’s deaf daughter in the

independent feature LISTEN TO YOUR HEART, for which she won the Best Actress Award at the

Los Angeles Cinema Festival in 2010. Alexia starred in the short films MARY LAST SEEN and

PANDEMIC, both of which went to Sundance in 2009 and 2010, respectively. Along with THE

COMEDY, she can be seen in Sundance Selection CALIFORNIA SOLO this year, in which she stars

opposite Robert Carlyle and Danny Masterson. Alexia grew up in Los Angeles and now lives in

Brooklyn, New York.

Gregg Turkington (Bobby) – a Los Angeles-based comedian and writer best known for his

stand-up comedy character Neil Hamburger. His TV and film appearances include Disney’s

“Gravity Falls,” “Jimmy Kimmel Live,” TENACIOUS D IN THE PICK OF DESTINY, “Tim And Eric

Awesome Show, Good Job!” “Red Eye,” “Adventure Time,” and “The Marvelous Misadventures

of Flapjack.” He has released numerous comedy and musical albums and DVDs, and performed

extensively throughout the USA, Canada, Australia, Japan, and the UK. His work has been

published in McSweeney’s and Maxim.

Rick Alverson (b. 1971) is a filmmaker and musician from Richmond, Virginia. His previous films include The Builder (2010), an existential character study of an Irish immigrant at odds with the promise of America. New Jerusalem (2011), starring Colm O’Leary (The Builder) and Will Oldham (Matewan, Old Joy), again considered the immigrant experience but this time through the lens of religious ideology. New Jerusalem premiered at the 40th International Film Festival Rotterdam and SXSW in 2011. Also in 2011, he was awarded a Visual Arts Fellowship from the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts. He also has directed videos for Bonny Prince Billy (New Wonder) and Gregor Samsa (Jeroen Van Aken). Upcoming films include a reconstruction era drama entitled Clement, to be produced in 2012, and Rabbit, both of which continue his collaboration with Colm O’Leary. In addition to his directorial work he has released 9 records on Jagjaguwar, most recently with his band Spokane in 2007.

Mike S. Ryan, producer – An Independent Spirit “Producer of the Year Award” Nominee and one of Variety’s 2007 “10 Producers to Watch.” His films have garnered nominations and prizes from the Academy Awards, Independent Spirit Awards, Gotham Awards and many more. JUNEBUG, starring Amy Adams, made its international premiere at Cannes in 2005 and went on to be one of the lowest-budgeted feature films ever nominated for an Oscar (Best Supporting Actress, 2005.) His credits include Todd Solondz’s PALINDROMES and LIFE DURING WARTIME; Kelly Reichardt’s OLD JOY (winner, Rotterdam International Film Festival 2006) and her recent MEEK’S CUTOFF starring Michelle Williams; Ira Sach’s 40 SHADES OF BLUE (winner, Sundance Film Festival 06); Hal Hartley’s FAY GRIM that starred Parker Posey and Jeff Goldblum (Toronto 2007) and Ilya Chaiken’s LIBERTY KID (Winner of HBO’s Latino Film Festival in 2007 and in competition at the Los Angeles Film Festival); He just completed post-production on BETWEEN US starring Julia Stiles and Taye Diggs. His current films are LOSERS TAKE ALL (Woodstock ‘11) and THINK OF ME (Toronto ‘11). Mike is a New York City native and NYU Tisch School of the Arts graduate.

Brent Kunkle, producer – His latest work includes a slate of “pulp” thrillers with Glass Eye Pix and Dark Sky Films, which include Joe Maggio’s BITTER FEAST, Jim Mickle’s STAKE LAND (Midnight Madness award winner at 2010’s Toronto Int’l FF) and James Felix McKenney’s HYPOTHERMIA starring Michael Rooker. Brent began his career assisting at indie non-profit film champion IFP, and then joined Iridium Entertainment for a short period as a producer’s and development assistant. He later transitioned into film production as production coordinator and music supervisor on LIBERTY KID (Winner of Best Picture at the 2007 NY Int’l Latino Film Festival) produced by Mike S. Ryan and Larry Fessenden. In 2007, Brent began working full-time for Fessenden at Glass Eye Pix. There he has served as line producer on I SELL THE DEAD, starring Dominic Monaghan and Ron Perlman, production supervisor on Ti West’s THE HOUSE OF THE DEVIL, and production manager on James Felix McKenney’s SATAN HATES YOU. He co-produced JT Petty’s short film BLOOD RED EARTH and produced Graham Reznick’s 3D short film THE VIEWER. He is currently producing Aram Garriga’s feature documentary, AMERICAN JESUS.

Mark Schwartzbard, director of photography – studied film at Ithaca College, then moved to New York and spent a decade working as a camera assistant on films including Woody Allen’s HOLLYWOOD ENDING, and Martin Scorsese’s THE DEPARTED, as well as LITTLE CHILDREN, RENT, HITCH, POLLACK and, the most fun of all, BORAT, which led to work as a camera operator on director Larry Charles’ next few projects, including RELIGULOUS and BRUNO. He also went through a period of working on many of the episodic TV shows filmed in New York, including “Ed,” “Sex and the City,” “Third Watch,” “The $treet,” “Hack,” “Philly,” and the “Law & Order” franchises. As DP Mark has shot nine narrative feature films (including THE DISH AND THE SPOON, starring Greta Gerwig, and THINK OF ME starring Lauren Ambrose), three documentary features, many shorts, and the Showtime series “La La Land.” He now divides his time between New York, Los Angeles, and wherever the next job is.

Michael Taylor, editor – a New York City-based film editor. His narrative credits include Julia Loktev’s THE LONLIEST PLANET, starring Gael Garcia Bernal, a Toronto, New York and London Film Festival selection, and winner at AFI; Loktev’s DAY NIGHT DAY NIGHT, winner of Le Prix Regards Jeune at Cannes, and Bryan Wizemann’s THINK OF ME, starring Lauren Ambrose, Dylan Baker and Penelope Ann Miller, a Toronto and Hamptons Film Festival selection, and Spirit Award nominee for Lauren Ambrose, best actress. He also cut Michael Walker’s PRICE CHECK, starring Parker Posey, a selection of this year’s Sundance Film Festival

Gene Park, sound re-recording mixer – a Brooklyn, NY-based post sound editor/mixer, musician, and recording engineer. A graduate of Columbia University’s music program, Park transitioned to film sound three years ago after playing music for a decade. Since then he’s edited, designed, and mixed six Sundance-accepted and eight SXSW-accepted narrative features, including TINY FURNITURE (dir. Lena Dunham – IFC Films) and BAGHEAD (dir. Duplass Brothers – Sony Pictures). He also handles post sound at The Criterion Collection, re-mixing, mastering, and restoring films ranging from Charlie Chaplin’s MODERN TIMES to Lars Von Trier’s ANTICHRIST. As a musician, Gene has performed, toured, and recorded with several bands including Mates of State and Rogue Wave, and has more recently been collaborating with just-intonation and minimalist composers.

FROM JAGJAGUWAR Here it is! Jagjaguwar is happy to bring you the soundtrack from Rick Alverson’s “The Comedy.” Featuring songs from artists both old and new, the music was chosen to exemplify“the autumn of the American Era.” You’ll find the full tracklisting below! The soundtrack is out November 13 on both digital and vinyl formats. In addition to the soundtrack, we’re happy to also share the official film trailer. Watch above!“The Comedy” is out via On Demand (Cable VOD, iTunes, Amazon, VUDU) starting October 24and in theaters on November 9; look for showings throughout the month with filmmaker Q&A’s in select cities! Head to Tribeca to find out where you can watch “The Comedy.” “The Comedy” Official Soundtrack Track Listing Donnie & Joe Emerson – “Baby” “Taxi Hip Hop” Bill Fay – “Garden Song” “Old Man Be Dead By Now” Gardens & Villa – “Carrizo Plain” Amanaz – “Khala My Friend” “You Get A Lot of Assholes in Here” William Basinski – “The Disintegration Loops” (1.1 Excerpt 1) “I Need You” Gayngs – “The Gaudy Side of Town” (Single Edit) “You Are in the Demon’s House” Here We Go Magic – “Over the Ocean” Bill Fay – “Camille” “Nick Nolte” Gardens & Villa – “Chem Trails” William Basinski – “The Disintegration Loop” (1.1 Excerpt 2)

Website: /html/thecomedy.html