Sudden Storm: A Wendigo Reader

writer. Larry Fessenden (2016 Non Fiction, Soft Cover, 158 pages)

Chris Hibbard, Bernice M. Murphy, Alison Nastasi, Victoria Nelson, Kim Newman, Samuel Zimmerman

Fessenden and the contributing writers and artists to SUDDEN STORM examine the Wendigo from several perspectives. The book’s thirteen essays explore the mythology from a crypto-zoological point of view, where it’s been portrayed as a ferocious yeti-like monster, a half man-half stag creature, a troll, or even just the wind itself. The book will also examine the Wendigo’s disturbing true-crime legacy, chronicling historically documented incidents of grizzly cannibalism attributed to the “Wendigo Psychosis”. The concluding essays contemplate the broader metaphors proposed by the mythology about Western expansionism and the resulting devastation to native peoples and the environment.

The Demon Hunter's Compendium

5/9/2017

Book Review – Sudden Storm: A Wendigo Reader (Larry Fessenden, 2015)

Entertainment Weekly

Clark Collis 2/16/2016

See the first images of Wendigo from horror director Larry Fessenden’s new book

The Wendigo has some way to go before it joins the likes of Dracula and Frankenstein in the Monster Hall of Fame. But horror director Larry Fessenden clearly feels there is plenty of terror to be mined from this terrifying creature, which derives from Native American mythology and has been depicted in a variety of ways over the years. The filmmaker has directed two movies directly inspired by the beast (2001’s Wendigo and 2006’s The Last Winter) as well as an episode of the NBC horror anthology show Fear Itself starring Doug Jones as a man who develops a taste for human flesh — a recurring theme in tales about the creature.

The Wendigo even features in last year’s video game Until Dawn, which Fessenden wrote with longtime collaborator Graham Reznick. “This just shows a man who clearly has very few ideas but can really milk them for all they’re worth!” jokes the filmmaker, whose other directorial credits include 2013’s killer fish movie Beneath and is also one of the creative forces behind the Tales From Beyond the Pale spooky audio play series.

Fessenden’s latest project to concern the legend is a collection of essays and other materials called Sudden Storm: A Wendigo Reader, which the filmmaker has curated and will be published by Fiddleblack on Feb. 16 (the book is now available to preorder from the publisher’s website). Deliberately broad in scope, the chapters range from one penned by President Theodore Roosevelt, in which he recounts a “goblin story” he was once told by an old hunter, to a consideration of the creature’s appearances on the small screen by horror expert Samuel Zimmerman. Sudden Storm also boast illustrations from Gary Pullin, Isabel Samaris, and renowned poster artist Graham Humphries. “We discuss it in terms of folkloria, in terms of crypto-zoology, but then we talk about it in movies and TV,” reveals Fessenden. “There’s a lot to chew on, if I can use the expression.”

Fessenden first became interested in the Wendigo as a child. “When I was in second grade, this teacher would tell us stories and he described this deer creature running through the woods crying ‘Wendigo!’” the filmmaker recalls. As an adult, Fessenden investigated the myth further and, in time, the subject became something of an obsession. “It’s an Ojibway legend that proposes that if you are in the wilderness, and you succumb to cannibalism, you will then absorb the spirit of the Wendigo, and become a voracious, hungry, creature that will keep growing, and you’re hunger will never be satisfied,” he explains. “It was a cautionary tale against cannibalism — rather specific, I think, but maybe in those times it was an issue. What’s interesting is, unlike the werewolf, or the vampire, or the Frankenstein monster, it really is an elusive creature. It’s depicted — which I think is so delightful — like a dwarf, or like a giant, or like a stag-monster, which is how I’ve sort of seized on it. What I love is that it does sort of slip through the fingers and therefore it becomes more mysterious.”

Given Fessenden’s well-known interest in the subject, it is little surprise that Fiddleblack sought him out to oversee Sudden Storm. “It’s a fun collection of strange and odd things,” he says. A lot of people are covering the same ground but not approaching it in exactly the same way. I have somebody (Flavorwire writer Alison Nastasi) who insists that Cannibal Holocaust is about the Wendigo. So, it follows an interesting trajectory. And this speaks to this thing that obsesses me about the Wendigo, which is that it’s slightly intangible and yet you can get an essence of it.”

Fessenden may not be finished with the Wendigo — or, maybe, the Wendigo is not yet finished with him. The director admits he would consider remaking his film Wendigo, which originally starred Jake Weber and Patricia Clarkson. “I feel like I never depicted the creature right,” he says. “I think I captured some of the mood in The Last Winter — the sort of oddness and off-kilterness. [But] I agree with Guillermo del Toro and a few others who say, ‘I want to see the creature! F–k all the Val Lewton bullshit! Let me see it!’”

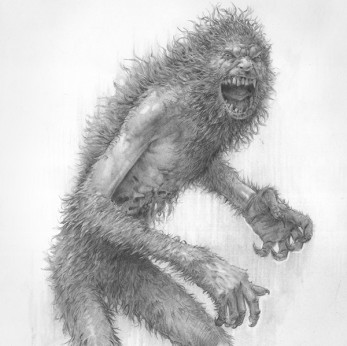

Above, you can exclusively see artist Hugo Silva’s depiction of the Wendigo — which decorates the cover of Sudden Storm — while, below, you can see Isabel Samaras’ illustration of the creature.

Blumhouse

Gregory Burkart 3/4/2016

SUDDEN STORM: A Literary Tribute to North America’s Most Terrifying Monster

Fans of indie horror are no doubt familiar with the work of Larry Fessenden — not only through his deeply personal horror films like HABIT and THE LAST WINTER, groundbreaking audio drama series TALES FROM BEYOND THE PALE and memorable roles in I SELL THE DEAD and WE ARE STILL HERE, but also through his production company Glass Eye Pix, which recently celebrated its 30th Anniversary.

But if you’re really serious about Larry’s creative output, you might have noticed a recurring motif running through much of his work: North America’s indigenous legend of the Wendigo, one of the most powerful mythological creatures ever to terrorize humankind.

Fessenden pays loving tribute to his diabolical muse in the new bookSudden Storm: A Wendigo Reader, in which he has compiled numerous essays, tales, journal entries and other literary works about the Wendigo legend and its influence on history, culture, art, and psychology… all accompanied by incredible illustrations by acclaimed artists like Gary Pullin, Graham Humphreys, Isabel Samaras, Trevor Denham, Betsy Heistand and Fessenden himself.

Having delved into this book from cover-to-cover, I can say that it came as quite a revelation; while I’d seen his feature film WENDIGO and his amazingly creepy “Skin and Bones” episode of FEAR ITSELF (my all-time favorite Wendigo tale), I had no idea how intimately the lore of this horrific monster was woven into Larry’s creative life.

I won’t divulge some of the best surprises in store, but rest assured you’ll be bowled over by some of the research Fessenden and his fellow authors bring to the party… say, for example, did you know that U.S. President Teddy Roosevelt knew at least one tale of the Wendigo? Me neither, but it’s right there on page 41 (in my copy, anyway).

Some of my favorite contributions include Alison Natasi’s intriguing analysis of the link between Ruggero Deodato’s CANNIBAL HOLOCAUST and the Wendigo legend; Carter Meland’s examination of the Wendigo’s influence on Antonia Bird’s horror-western RAVENOUS; and Samuel Zimmerman’s overview of the Wendigo’s treatment on television shows like THE X-FILES, SUPERNATURAL, SLEEPY HOLLOW and — of course — FEAR ITSELF. Also enlightening is Chris Hibbard’s historical account of “Wendigo Psychosis” (a well-documented condition) as it relates to real-life crimes throughout North American history.

It’s still shocking to me that this terrifying, archetypal monster hasn’t become as entrenched in American folklore, media and popular culture as vampires, werewolves and zombies… Larry’s taken some significant steps to changing all that, and hopefully this book may inspire other creative minds to further explore this monstrous myth.

Dread Central

Debi Moore 2/22/16

Larry Fessenden’s Sudden Storm: A Wendigo Reader Available Now!

Movies about the Wendigo have met with mixed success so now it’s time to use a new medium to explore the legend. Filmmaker/actor Larry Fessenden, who wrote and directed 2001’s Wendigo, can now add “curator” to his long list of accomplishments with the publication of Sudden Storm: A Wendigo Reader from Fiddleblack.

The book’s thirteen essays explore Wendigo mythology from a cryptozoological point of view, where the being has been portrayed as a ferocious yeti-like monster, a half-man/half-stag creature, a troll, or the wind itself. Sudden Storm features full-color artwork by prominent illustrators, bringing many iterations of the elusive creature to the page, implicitly posing the question: How do we conceptualize both the malevolent and benevolent aspects of the Wendigo?

Along with Fessenden, the authors include Victoria Nelson, Carter Meland, Kim Newman, Bernice M. Murphy, Samuel Zimmerman, Sheldon Lee Compton, Chris Hibbard, and Nathan Carlson.

It’s a fun read for monster and horror fans, Larry Fessenden fans, and people who like pop culture. In fact, there’s probably not another cool book dedicated to the subject.

Daily Grindhouse

Patrick Smith 08/1/2016

[THE DAILY GRINDHOUSE INTERVIEW] HORROR ICON LARRY FESSENDEN!

As some of you might remember, a few months ago I wrote pretty extensively about the films of Larry Fessenden. It was a pretty deep dive into the work of a director who effectively shaped my tastes in more ways than I probably realize, both through his own films, and through the ones he godfathered into existence through his production company, Glass Eye Pix. So I jumped when the opportunity came up to interview him about his filmmaking and about the very cool book Sudden Storm: A Wendigo Reader which he curated, a work focusing on the distinctly American myth that has come to be so closely associated with him.

Sudden Storm collects over a dozen essays, interviews, and script excerpts focusing on the Wendigo myth. Some focus on the pop-culture canon of the creature, of which Fessenden is definitely a prime mover, whereas others focus on the roots of the very myth itself, and how it still creeps within the darkness of the woods of Northern America to this very day. There’s a breadth of knowledge on display that makes this necessary reading for film buffs and for urban legend enthusiasts alike.

And no one is more enthusiastic about this stuff than Fessenden himself. I was pretty aware of his filmography and of the depth of knowledge each film of his tackles in terms of individual mythologies, but Fessenden’s enthusiasm was practically infectious. A natural raconteur, we talked for a good thirty minutes, and I would have gladly talked to him for thirty hours. In the following interview, we cover everything from howSudden Storm came together, America’s odd relationship to its own mythology, what technology says about our stories, the sleight of hand that is modern film financing, and the question of ownership in film.

Patrick Smith: First and foremost, let’s talk about Sudden Storm, which is a new book that you curated, which is all about the Wendigo myth, which is also the basis for what is, in my opinion, your best known movie, 2001’s WENDIGO. So I guess my first question is: How did this project originally come about?

Larry Fessenden: Well the original movie, very briefly, was generated because I had made a film calledHABIT, and I got an award for that, gained some accolades, and so Hollywood said, “what do you have next?” And I had a non-horror project, which seemed to be a terrible strategic move, so I went home after some meetings in Tinseltown and I thought, “Horror, horror, horror… let me think, let me think…” and I realized I had this memory as a child of being told this story of the wendigo creature by a third-grade teacher. And I basically set out to write a script that was a series of memories that had this specter in it, of this “deer-man,” which is how the teacher in third grade had described it. Later on I did some research, and I found out that the wendigo as mythology from the Ojibwe nation really aligned with a lot of my thinking. It’s a cautionary tale about overreach and hubris, and it’s essentially trying to teach the natives not to eat each other in times of extreme duress, in the winter, in the woods, when you’re stranded. “Do not eat your fellow man or you will be possessed by this evil spirit.”

And I feel somehow that speaks also of a greater theme in my thinking about consumption and the way that the white man in general deals with the planet, indigenous people, the poor, the destitute, and so on. So it was a theme that really resonated with me, so I made WENDIGO, I made THE LAST WINTER which also had the wendigo creature, I made another film called SKIN AND BONES, which is another way of looking at the wendigo. Then this press called me and asked me if I wanted to do a book on the mythology, and I thought it would be worthwhile because there are just so many different ways to look at this mythology, that it really is worth exploring. But I didn’t want to write it, I wanted different voices to chime in, and that’s why I became the curator of this little volume.

Patrick Smith: It’s a very diverse group of authors you’ve assembled, everyone from anthropologists to more pop-culture-oriented writers, and you even do an interview with Christian Tizya. Were these all authors you were already aware of, did you have to seek them out, or have people pitch you as the project came into focus?

Larry Fessenden: Well the cool thing is that over the years, because I became associated with the wendigo, I would get e-mails from strangers and scholars. And then by chance, over time if you do a search of yourself now and again, you’d go, “Oh that’s cool, someone wrote a thesis on THE LAST WINTER and how it’s an important environmental story,” so it was really just over time and collecting articles relating to either my own work or to the wendigo itself. I do love the pursuit of clear articulation of this mythology, which is so incredibly elusive, and what I think makes it interesting is that it’s getting at something, but its not entirely clear what, and that’s because it’s [been] through many filters. It’s a very genuine native mythology, that was then sort of usurped by Algernon Blackwood, the famous British writer who wrote the short story “Wendigo.” It’s been in movies and even now TV and comic books, and so there areso many ways to experience the creature. The question becomes: so what is the common theme?

One of my favorite articles is [the one where] I asked Kim Newman, whose a great writer out of the UK to just give me an overview of all the wendigo movies, and that’s one of my favorites because its all about the pop culture resonance. There there are just such a diverse amount of articles that have approached the story from different angles.

Patrick Smith: Yeah, reading the book, the Newman one was one of my favorites too, along with Sam Zimmerman’s, but I’m coming from it from the pop culture side of things, so that’s definitely what I’m going to zero in on.

Larry Fessenden: Yeah, exactly.

Patrick Smith: If we could talk for a minute about the nature of myths, you were sort of talking before about how the white man takes some of these myths, and wraps them around themselves and usurps them. As far as I can tell — American myths are sort of a weird thing. We don’t really have them, except the ones from the indigenous peoples, which were beat down into the ground but refuse to die. So as someone whose worked with other myths, what do you think it is about myths in general that make for good storytelling, in genre or otherwise, and how in America those are used?

Larry Fessenden: My basic theory is that we have to understand how important mythology and basically narrative is to the way we perceive the world, and so by taking vampires and werewolves and analyzing at the same time as enjoying their potency as stories, but also having an eye towards why they’re relevant to us. I think that gives insight into the fact that humanity is driven by a narrative structure, I think that separates us from other creatures. Its important because if the narrative is false or ignites peoples passions for the wrong reasons, it takes us in the wrong direction, then it has a tremendously destructive force, and of course I’m talking about the American political system, the idea of capitalism as the only solution to the design of society. These are all mythologies, it’s important to understand that a lot of the assumptions we make as people going about our business are simply constructs. So I feel that very passionately, and I also enjoy the fun of just telling a story about a creature that will grow because it’s always so hungry.

But that speaks of something very profound, which is our notion that growth is a positive force. You always feel politicians left and right talk about growth –“we have to grow the economy” — well, that’s impossible in a finite world, to continue growth. So maybe, maybe, that’s a mythology that doesn’t make sense. So I think the first thing you have to do is see that you are being manipulated, and that you’re following a mythology, and the next thing is to say, “whats another way to look at it?” So that’s why I think even a little humble volume likeSudden Storm is trying to peel away the onion and just try to understand how we think about the world — “we” meaning society and different people: Indigenous, white man, whatever it is.

So that’s my love of mythology, because on the one hand I’m charmed and captivated by it, and on the other hand, I want to be sure we realize that it is a construct that is guiding our lives, and you have to be able to step outside of it. I always say that my films are actually a critique of religion in some way, and there are many religions that we operate under; the religion of capitalism, Christianity, Judaism, good versus evil, the religion of progress; these are all things that we assume are true, and that the world is built around those, but actually it’s just the way our brain operates. As for American mythologies, I think we’ll find that most profoundly in the Marvel universe, all of those stories are about good and evil, all the superhero movies that we’ve been ideated with are sort of our new Greek gods. There’s lots of people with special powers, some people have a hammer, some people get inside a machine and fly around, that’s our way of processing reality, and to me, all mythologies are simply the way we process reality. And it’s good to know that, so that you can step outside of it and have some control over your passions.

Patrick Smith: I heard a rumor once that you tried going after Werewolf by Night? Is that true?

Larry Fessenden: Oh definitely.

Patrick Smith: Wow.

Larry Fessenden: Funny that Marvel, they’re doing so well, but you can tell that they think that property isn’t worth much. I mean, in a weird way, I love Marvel Comics because I read Tomb of Dracula, the Monster of Frankenstein, and Werewolf by Night. I never really read superhero comics, which is why I think I’m a perpetual outsider outside the cultural norms. Those were beautifully illustrated by Mike Ploog, among many others, but he and Werewolf by Night were always my favorite. Of course I can make my own werewolf story, I don’t need that comic book, but I had some meetings at Miramax back in the day, and I always made it very clear that storyline was very captivating to me. It was just about a guy named Jack who had a badass father who he had problems with, and every month he would turn into a werewolf! It was a great, serialized soap-opera of sorts, and I loved the way that the werewolf was depicted.

But they didn’t want me!

Patrick Smith: [laughs] Well, you never know. Once they get done with this next big batch, they could go a little weird. Chris Evans costs more than they’re willing to pay, and then BAM! Werewolf.

Larry Fessenden: [laughs] Well when they went weird last time, it worked for them, right? IsGUARDIANS OF THE GALAXY even Marvel? I don’t even know.

Patrick Smith: Yup, that’s them.

Larry Fessenden: That was more fun than I was expecting. I understand that CAPTAIN AMERICA: CIVIL WAR was great, but there’s sort of a tiredness to seeing those dudes in suits all the time, its just getting a bit much and they absorb all of our greatest actors. They suck ‘em up and put them in tights. I don’t know what’s going on with that.

Patrick Smith: Well, I guess their thinking is, if you have them, you might as well lock them down.

Larry Fessenden: Well, I can’t blame them.

Patrick Smith: To backpedal a little bit, you were talking about myths in the modern context of the political system, or attaching them to these larger structures, so I’m wondering how you think myths will interact with technology? Out of curiosity, did you see UNFRIENDED?

Larry Fessenden: No, but I actually — that was a terrifying trailer, and I wondered if it was a good movie, but I didn’t see it.

Patrick Smith: It’s definitely interesting, the reason I bring it up is because it basically creates a new kind of ghost story based in technology. Basic idea is, if you accept a chat message from someone who’s dead, that ghost can now haunt you through your computer. I don’t know if that was a real urban legend before, but it’s definitely a thing now.

Larry Fessenden: Well, some of the Japanese horror used that — obviously RINGU was about the TV and the videotapes and those things haunting you — it’s only logical that we have these kind of stories. I think it’s essential.

What I love about horror is that it really has to speak to the time, and it’s one of the reasons I’ve often criticized remakes, because they are sort of dredging up stories that were right for the era but maybe aren’t as relevant now. So UNFRIENDED, even though it’s not a movie I saw, I immediately liked where it was going, because it was making something vital and common in kids’ lives and finding the threatening element in there, which is always worth finding, because there’s always the dark side in our most beloved institutions.

And I just like bringing that up and making people think about what they take for granted!

Patrick Smith: Yeah, and sometimes these things interact with the real world in real ways. Like that documentary coming out about the SLENDERMAN.

Larry Fessenden: Yeah! Funny you mention that — I was just talking about SLENDERMAN. I don’t know a whole lot about the backstory, I just briefly watched at least one version of some of the YouTube stuff, but in general, I just like that that exists out there. Its creepy and — look, it’s an aesthetic thing to like horror, and to like the spooky things in the world, and technology does not exempt us from those things. In fact, it’s very creepy and insidious and all in our lives, so it’s appropriate to write stories about our interaction with all this new creepy stuff. It doesn’t have to be a creaky old house to be scary.

Patrick Smith: I don’t think there’s any real comparison — Internet’s already scarier than we can think up.

Larry Fessenden: Well, that’s frickin’ true. The thing about the internet that’s scary is that it speaks to the madness of crowds, and the debasing of face-to-face dialogue, which allows people to feel empowered as they sit at home getting irate, as we all do, about the littlest things. But when you don’t have to look someone in the eye and follow through on your outrage, then you can keep fueling that discontent. Whereas, usually if you’re sitting in a room with someone, you can kind of go, “Ah, well listen, we’re all in this together!” So it’s ironic that the internet connects us, and it alienates us from each other, and I think these are very serious issues that society isn’t entirely able to deal with, because it’s coming at us so fast. Always with a smile, always with a great new product from Apple, and yet it’s important to be a little wary of, once again, the mythologies that run our lives. Which is that every new shiny bauble is good, every new technology is advancing society… but is that true? Is it possibly disconnecting us from each other, is it possibly making us feel alienated and more violent?

Patrick Smith: Its a good question, and honestly I don’t have an answer. Although my default is “Yeah, the internet’s gonna bring us down” but I’m a big TERMINATOR fan, so of course I’m going to believe that.

Larry Fessenden: [laughs] Exactly. Well the beauty is that we’ve all been raised — or at least our circle of perverted crazy people of horror and sci-fi — we’ve lived and breathed cautionary tales since beforeFRANKENSTEIN, since Prometheus. That’s the thing I love about horror and the darker genres, is that it really looks humanity in the face and says “Are we doing all of this correctly? Are we not succumbing to our weaknesses? Will this all blow up in our face?” It’s amazing thatFRANKENSTEIN remains such a vital myth, because it really says, “Do we now what we’re doing with science and technology?”, assuming it’s always for the good. So these are great questions to ask, and yeah the whole TERMINATOR thing, and all of these wonderful scary movies ask that question: “Are we doing it right?”

Patrick Smith: Those questions generally anchor most of my favorite movies in the genre which, incidentally, you’ve had a hand in more than a few as a producer through your company Glass Eye Pix. Looking at your IMDB page, the amount you’ve been involved in, from acting to producing, is pretty astonishing. However, it’s become pretty clear that distribution models have changed pretty radically in the last five to ten years. Video stores aren’t really a thing anymore, DVD sales overall aren’t great, so it seems like it’s all coming down to theatrical or VOD. So I’m curious, as a producer, how you get these films financed, and maybe even get a little money in the bank for yourself.

Larry Fessenden: Well, you’re absolutely accurate in your questioning. It used to be that I could invest my own Glass Eye coffers into a film, and then I would double the money, or at least make it back, and that gave me reason to go forward with the next project. That was a glorious period in the early 2000s, video was looking for content, and it was really a great period, and it’s why I think in the analysis of it all, I was able to establish Glass Eye Pix and make movies for myself, and with people like Ti West, Graham Reznick, Jim Mickle, and Glenn McQuaid.

[Pause] Now you need a very direct relationship with Netflix and stuff, so I don’t feel quite as set up or assured. Those are major companies, and they’re quite generous, but you usually need a middle man, and it’s changed things a little. I’ve been fortunate enough to have an association with MPI, which is also known as Dark Sky Films, and I’ve made about six movies with them over the years, and in that case they’re providing me with the budget. Obviously I’ll skim a little off the top for operating costs, and that’s how we stay afloat and make some really great movies. But I don’t own those movies in the same way I owned my earlier films. So everything different, my own films likeHABIT, WENDIGO, THE LAST WINTER… those are now all under one roof at IFC, and I get to share a little participation when they sell those. So I’m like a hobo, just going from one possible opportunity to another, trying to keep new talent protected from the harsh winds of the marketplace and to stay afloat myself. It’s rough, it doesn’t get any easier, since everything keeps changing, and you keep having to figure it out.

Patrick Smith: So if you own those, does that mean you don’t own BENEATH? Which is a movie I liked quite a bit, but I know it got roughed up a little bit —

Larry Fessenden: [laughs] That movie was severely maligned, and maybe misunderstood. There were a few snarky reviews which I think kind of sunk it, if I can use the term, but there were also some thoughtful people that didn’t like it. I’ve always appreciated those that see it as a nasty little satire, or whatever they got out of it, because I think it’s a cool movie and I love the kids that are in it. One of the weird knee-jerk things is people saying, “Its terrible acting!” and I reject that completely.

In any case, it’s a soft spot for me, because it’s the first movie I made in what I’ll call the “trolling generation” –I came out of the theater and felt really great about my screening, and within two and a half minutes, I had two jackasses reviewing it like it was the worst movie ever made, which to me felt utterly silly. You just sort of realize the ego involved in internet culture, just quick snarky commentary. And listen, I’m not a lone victim of that. Everybody feels the burn, just really being dressed down and the whole culture has gotten preposterously unthoughtful.

But the answer is I made BENEATH for Chiller Films, which was a good experience. We got a pretty good budget, but it was still a strain to make a film on the water and all that, but as far as going in knowing it was a low-budget movie, we did pretty well. But that was truly a work-for-hire, it wasn’t my script, which was very different from my own films, which were produced independently, which I had a bit more say in how they were put out.

Patrick Smith: So going into the future, I would imagine you’ll direct again, so would you do work for hire again, or try and stick with what you’ve done before and control what you make completely? Or would it depend on the project?

Larry Fessenden: It would depend on the project, depend on the script. I will add that there’s no such thing controlling the work completely, because if you’re a responsible artist, you have to be aware of the realities. Either the investor has concerns about your cast, your ending, your storyline, your budget, so you’re always mindful of the two worlds of commerce and the arts, and they can live very happily together. Everybody knows I’m a fan of Hitchcock — he felt great responsibility towards his investors, and I always do too. At the same time, you have to protect the artistic impulse, the only things that are exciting are those that come unexpectedly from individual voices in the arts. To make movies by committee, and to try to anticipate and pander to an audience, is simply to fill the air with deadening work. So it’s very very important, as a matter of principle, to protect the artistic vision.

Anyway, thats how I’ve always looked at it, but I would direct someone else’s script. It’s all just circumstance. In the end, and I appreciate you asking, because I really I’m here to make my own stories, because they are quite specific to me and my own sense of what cinema can be. And that’s why I defend other artists, because I think my vision should also be defended. BWA-HA-HA!

RogerEbert.com

2/16/2016

HELL TO PAY: INDIE HORROR ICON LARRY FESSENDEN ON WENDIGOS AND UGLY AMERICANS

Indie horror icon Larry Fessenden is an American original. As a filmmaker, Fessenden’s movies often concern American exceptionalism, and a general sense of foreboding about our culture’s unexamined prejudices. But Fessenden even stands apart from contemporaries like Eli Roth, another horror-master whose work focuses on Americans’ regrettable lack of self-awareness. With abundant gallows humor and an inviting fascination with mythic iconography, Fessenden makes movies that don’t conclude with the end of the world as we know it, but rather suggest a more ambiguous, semi-optimistic post-human future. This is true of Fessenden-helmed films like “Wendigo,” “The Last Winter,” and “Skin and Bones,” Fessenden’s excellent contribution to the short-lived “Fear Itself” television anthology. Fessenden continues that focus with “Sudden Storm: A Wendigo Reader,” a new book of essays edited by Fessenden and written by horror experts about Native American folklore, and the depiction of cannibalism and environmental portents in the media. RogerEbert.com spoke to Fessenden about Wendigos, Donald Trump, “Funny Games” and more.

When we last spoke in 2010, you talked about “American exceptionalism” as being part of what makes your films uniquely American. In light of that thematic focus: what would you say are some of the distinguishing characteristics of the wendigo narrative?

Americans think we’re exceptional, but we’re not. As we become a stupider nation in our discourse, there has become more posturing and chest-thumping. The “wendigo” fits in as it is concerned with a kind of American expansionism that’s been going on since we first touched this country’s shores, taking over native population’s land, giving them diseased blankets, and generally having our way with them. As if we had a right to this land. The myth of the wendigo comes from the Canadian, Northern Algonquin tribes. What I find intriguing about that story is how it can be applied to expansionism: taking over the land, and also taking over other people. To me, wendigo mythology has great resonance, whether it’s a cannibal story, or a much broader comment on western culture destroying native people, and the environment. Which is where we are now. Global warming is the final frontier of wendigo-ism! [Laughs]

Cannibalism is often seemingly used in horror films as a sort of revenge against capitalism, or just financial inequality. Like zombie movies, there’s a built-in class warfare element to it, though it often devolves into a war of all against all. What is unique about the wendigo and the fears we project onto it?

Well, cannibals seem to really freak people out. [Both laugh] Because it is about eating another person. I’ve never had the same reverence for humanity that most people do. I don’t eat animals either, except fish. So to say you could never eat human flesh … I see it all with a bit of irony, as an expression of narcissistic anxiety! Anyway, the wendigo is a fundamentally cautionary tale about not eating your fellow traveler in times of extreme duress, like if you were stuck in a winter storm. And extrapolating from that, the wendigo is a caution against over-reach, and rapaciousness.

It’s a corrective.

Exactly. And I think that’s how it was used in Native American cultures. Another thing that some of the authors in “Sudden Storm” discuss: there’s a very real condition called “Wendigo Psychosis.” And that’s a description of actual madness, not just a fear of something. It’s the fear that you’ll become possessed by the spirit of the wendigo. These people would become unhinged, and try to eat their families, in the way that you do when you’re unhinged. [Laughs] There are all of these intangible elements with the wendigo, whereas with werewolves it’s a much more clear description of a man/beast dichotomy. With Frankenstein’s monster, we understand that to be science run amuck. With the wendigo, it’s a little harder to grasp.

I mentioned cannibals and zombies because they’re the closest commonly-used analogue to the wendigo that we have in horror cinema. But the wendigo is, as you said, different from a cannibal in that the wendigo is based on folklore, and is therefore often an avatar of the environment. Talk a little about how you use the wendigo as a symbol of either environmental apocalypse or rejuvenation in your films.

Even that’s unclear. There’s only one mention of the wendigo in my movie “The Last Winter.” But you can see the creatures at the end of the film as some sort of nature spirit. A lot of people tended to see that as nature’s revenge, but I think of it differently: nature simply is. It’s the people’s sense of dread that overcomes them, and it is almost like a parable about guilt. When the world falls out of balance as it has, there is hell to pay. The wendigo is a way to discuss that. It’s manifested in different ways. Sometimes it’s a creature with antlers, and sometimes it’s something in the wind. In my film “Wendigo,” I have the creature appear as a bunch of sticks and branches. But in my movies, I always try to get at the fact that all of this is in the mind. And if your mind is troubled by what you’ve done, or by real, scary elements in your life, then maybe the wendigo will visit you.

In your introduction to “Sudden Storm,” you mention your first childhood introduction to the wendigo. Was that also the moment where it became an obsession of yours? Or maybe it was the time your mother frightened you by growling “wendigo” from the kitchen corner? Was there a later event that really turned a trauma into something you just couldn’t let go of?

I can’t think of any one incident. I came from a comfortable upbringing, no real trauma. But I think if you’re a very creative, sensitive kid, you’re aware—or I was aware—that this is a very fragile reality, and that it can disappear at any moment. I certainly could envision the dark possibilities in every moment. I was the third child, so it’s possible that my mother didn’t show me enough attention or something like that, really all subtle things that one could imagine. But the bottom line was that I was always oriented towards the horrific. I would read scary comics all day long, and would be terrified at night. It shows a sense of perversion that I never corrected that situation. And that’s what we do at Glass Eye Pix, [the Fessenden-founded indie horror production company.] The common misconception is that people who make scary movies are above it all. But I feel exactly the opposite. I always say that I’m afraid of everything and I want audiences to see the world like I do.

Look at Hitchcock: He was clearly terrified by the world at large, and wanted to torture other people. Well, I’m of that school.

As for the wendigo: that was a childhood story told by a teacher in second grade at story hour, and it became an image that stuck in my mind. It was very evocative. I told my mother about it, and she proceeded to hide in the kitchen closet and scare me. Anyway, the wendigo story really stuck in my craw. When I went to Hollywood, after making “Habit,” I pitched them something other than a horror movie. They said “Well, we really want a horror film from you. That’s what you do, isn’t it?” So I went and wrote the script for “Wendigo.” I had this strange reserve in my mind, a latent memory about this creature that had haunted me as a kid. I wanted to convey that to others. I have been obsessed with death for all of my 52 years, which is an interesting way to go through life. Once you’ve made it to 52 years, you realize you’ve wasted all that time worrying. [Laughs] And it will come anyway. The question is always when … and how.

Let’s go back for a moment: how does race play into mythology of cannibals? In your films “Wendigo,” and “The Last Winter,” as well as “Skin and Bones,” your episode of “Fear Itself,” you deal with this notion of appropriation and how white Americans are punished for what they probably see as a relatively benign kind of assimilation. How did you imagine dealing with that notion of privilege and manifest destiny?

Privilege is an important issue to address. Americans are so smug that they imagine that they are somehow entitled. You see this in public discourse; it’s incredibly discouraging. The presidential race is filled with pompous blowhards who are not really addressing the essential violence of industrialized societies. I love my technology as much as the next guy. But I just feel, philosophically, there needs to be a correction. Now at the same time, I am also part of this culture; I always try to give my villains humanity, because there’s a appealing characteristic in the adventurer, the explorer, and the exploiter. That’s why I cast Ron Perlman in “The Last Winter”: he’s the oil man, and he serves as the villain. But he’s robust and exciting. So I hope there’s contradictions in my movies. Just like Donald Trump has a certain appeal but at the same time he is toxic.

The basic assumptions we are living by are not sustainable. That’s a very cliched term in the environmental movement, but it’s an essential truth. What’s going to bring about our end is pursuing this fantasy of perpetual growth that stems from a disconnect from reality based on an arrogance about our own self-importance. Meanwhile, we’re destroying the poor classes, enslaving people. Maybe not literally, but it’s basically the same thing: Mexicans work in our slaughterhouses, pick our fruits and yet, we disparage them as lazy. It’s absurd. These people are the basis of our exploitive economy. Call me “bleeding heart,” if you will—emphasis on “bleeding.”

Now, is there an alternative? Yes, there is. There is such a thing as a more modest, measured society. How we can ever get back to that is a complete mystery in this culture. However, if you can’t even have that conversation, you’ll never get there. I’d like to think that that conversation has to start with some wake-up calls. And why not bring in some horror pictures to do that? That’s always been my orientation. I’m compelled to depict the dark side of Western civilization. I really think humanity is a virus, as I say in “The Last Winter.”

Since horror movies have that cathartic element, a lot of the genre’s milestones deal explicitly with taboos. Do you feel horror filmmakers have to be responsible in how they say or deal with certain issues? Like with “The Green Inferno”: some people say it’s not enough that Roth is inspired by films like “Cannibal Holocaust,” but rather feel they have to take it out of the context of his influences, his subject, his genre, etc.: it’s the power of the image that they worry about. Is that a fair critique for a horror film?

It seems crazy to make politically-correct horror movies. So while I can’t really trust Eli’s taste, I think he has a right to use shocking images to make his point, if he has one. I wasn’t a fan of his first film [“Cabin Fever”], and I was asked to sort of confront him in the press about it. I had made “The Last Winter,” at the time, so it was assumed that we were coming from different places. I thought “Cabin Fever” was a silly movie. But before I went and spoke any further in confronting him in the press, I watched the “Hostel” films. And I enjoyed them. I felt like he was poking fun at American exceptionalism. The characters are buffoons! They go to Europe and expect to have their way. But things don’t go well, there’s some comeuppance there, which I think is pleasing in a horror film. I haven’t seen “Green Inferno,” but I don’t assume it’s bad. It may well be offensive, but maybe it’s getting at something.

Is there a line that you feel a horror filmmaker cannot cross?

There’s certainly no decree that I would make. However, as I get older, I’m less inclined to just watch appalling things unless there’s a point to it. Extremely violent movies—that’s just not my scene. I’ve never really made it through “Inside;” I’ve only seen part of it. And I take issue with “Funny Games,” Michael Haneke’s “masterpiece.” I find it rude his presumption that I go to horror films to see people tortured. That’s not my motivation, and that’s what [Haneke] is accusing me of when he breaks the fourth wall in that film. So I find that pretentious, but what I do find effective in that movie is the cinematic brutality, and the cold-blooded murder of a child in front of its parents. That I find profound, and that kind of violence is 100% valid when it’s done in “Henry: Portrait of a Serial Killer.” Because there, the filmmakers are making a comment on this sub-culture of people in our society who are disconnected and very scary. That I find fascinating. It’s not like “Friday the 13th” and all those films, which I think are silly. A lot of people love those films, but I never liked horror for horror’s sake unless it’s in the atmosphere. So maybe I mean violence for violence sake.

Other movies that almost cross a line? I love “Man Bites Dog.” That’s technically a satire, but it’s incredibly brutal while also making a comment on horror, and violence, and the self-importance of the filmmakers. I love “Irreversible” … we’re talking about difficult movies to watch now. And my favorite movie of this extreme nature is “Angst.” They just re-released it on Blu-ray. It’s gorgeous, absolutely compelling, and shocking, unblinkered horror. That film could easily be said to cross the line: sex with corpses, horror, mutilation. And yet, the movie feels like it’s looking for truth, so it works for me.

As you get older, all violence is sad. And you get tired of it, because it doesn’t stop. Look at ISIS: I always say they’re making the best horror movies out there. There’s too much media, and in the end, you just want to retreat. It’s hard to continue to be confrontational, and persevere as if you’re going to make a difference. I feel exhausted with humanity.

If you could recommend one Wendigo narrative that you think a lot about, or one you think is especially emblematic, which one would it be?

I would start with Algernon Blackwood’s “The Wendigo.” It’s a very quick read, but it depicts an unknowable dread, where you don’t recognize people you thought you knew. Where the wind is crying out to you. Where somebody disappears from their tent, and you can’t make sense of what happened to them because their footprints disappeared in the snow, as if they were carried away. It’s incredibly evocative. If you are lucky enough to be reading “The Wendigo,” I also recommend “The Willows,” also by Blackwood. That’s usually in the same collection of short stories. That’s another story that has an unknowable fear. H.P. Lovecraft is credited with this style of horrific story-telling. But I’ll take Blackwood over Lovecraft. I know that’s throwing down a gauntlet for a lot of people, but for me Blackwood captures a more transcendent fear derived from our alienation from nature.

Other great Wendigo narratives … ? “Ravenous” is an amazing depiction of true insanity. And I always credit the score…

The Wendigo is a mighty, powerful spirit. It can take on many forms— part wind, part tree, part man, part beast, shapeshifting between them… It can fly at you like a sudden storm, without warning, from nowhere, and devour you, consume you with its ferocious appetite…

This book’s thirteen essays explore the Wendigo in its myriad forms and from various (pop) cultural perspectives. Readers of the book will experience full-color artwork and diversely written essays.

Between Algonquin mythology and field-noted cryptozoological points of view, the Wendigo is portrayed as a ferocious yeti-like monster, a half man-half stag creature, a troll, or even just the wind itself.

Sudden Storm examines the Wendigo’s disturbing true-crime legacy, chronicling documented incidents of grizzly cannibalism attributed to “Wendigo Psychosis”. Essays contemplate the broader metaphors proposed by mythology, regarding Western expansionism and the resulting devastation to native peoples and the environment.

This collection features brilliant new artwork by prominent illustrators, bringing various iterations of the elusive creature to the page, implicitly posing the question: How do we conceptualize both the malevolent and benevolent aspects of the half-beast entity?

Sudden Storm is a provocative reading experience for fans of Larry Fessenden’s oeuvre, fans of horror in film and fiction, and anyone intrigued by mythology and folklore.

LARRY FESSENDEN, recently saw the release of a box set entitled The Larry Fessenden Collection from the label Shout Factory featuring new transfers of his four most celebrated films, No Telling, Habit (Nominated for three Spirit Awards), Wendigo (Winner Best Film 2001 Woodstock Film Festival) and The Last Winter (Nominated for a 2007 Gotham Award for best ensemble cast). Fessenden directed Skin and Bones for NBC television’s horror anthology Fear Itself and the feature film Beneath for Chiller films. He is the co-writer with Graham Reznick of the Sony Playstation videogame Until Dawn. He is founder and CEO of Glass Eye Pix, a production shingle which celebrated its 30th year in 2015, and he is the producer of revered genre fare such as The House of the Devil, Stake Land, I Sell the Dead and the audio series Tales from Beyond the Pale.

CHRIS HIBBARD, is a poet, author and freelance journalist living in Lethbridge, Alberta, Canada. He was inspired to study the Wendigo legend while taking Native American folklore classes at the University of Lethbridge, but he admits to being attracted to the “spooky” side of life.

BERNICE M. MURPHY, is lecturer in Popular Literature at the School of English, Trinity College Dublin. She edited the 2005 collection Shirley Jackson: Essays on the Literary Legacy and has published many book chapters and reviews on horror cinema. Her recent publications include The Highway Horror Film (2014) and The Rural Gothic in American Popular Culture (2013). She has just completed Key Concepts in Contemporary Popular Fiction for Edinburgh University Press, and is currently co-editing (with Elizabeth McCarthy) the collection Lost Souls: Essays on Gothic Horror’s Forgotten Writers, Directors, Actors and Artists for McFarland. She is co-founder and was co-editor (from 2006-12) of the online Irish Journal of Gothic and Horror Studies and has directed the Trinity College M.Phil in Popular Literature since 2009.

ALISON NASTASI, is an artist and journalist from New York City. She is the weekend editor for the arts and culture website Flavorwire. Her work has appeared on Fandango, Moviefone, MTV, Rue Morgue, and more. She is a Chronicle Books author and contributing author in Satanic Panic: Pop-Cultural Paranoia in the 1980s.

VICTORIA NELSON, is working on the third of her Harvard trilogy after The Secret Life of Puppets and Gothicka. She is also the author of two books of short stories, a memoir, and a book on writer’s block and creativity. Victoria teaches in the Goddard College graduate creative writing program and lives in Berkeley, California.

KIM NEWMAN, is a novelist, critic and broadcaster. His fiction includes the Anno Dracula series, Life’s Lottery, Professor Moriarty: The Hound of the D’Urbervilles and An English Ghost Story; his non-fiction includes Nightmare Movies and BFI Classics studies of Cat People, Doctor Who and Quatermass and the Pit. He co-wrote the comic miniseries Witchfinder: Mysteries of Unland and the plays The Hallowe’en Sessions and The Ghost Train Doesn’t Stop Here Any More. He is a contributing editor to Sight & Sound and Empire magazines. His latest novel is The Secrets of Drearcliff Grange School.

SAMUEL ZIMMERMAN, is a curator at horror streaming site Shudder, and has previously worked as managing editor at Fangoria and editor-in-chief at Shock Till You Drop. Since, he’s honed both his writing and karaoke skills and been trusted with the responsibility of jury duty at Austin’s incredible Fantastic Fest. Zimmerman lives in and hails from The Bronx, New York where his pants are too tight and he’ll watch anything with witches.

SHELDON LEE COMPTON, is a short story writer and novelist who was born, raised, and continues to survive in Pike County, Kentucky.

He is the author of three books – The Same Terrible Storm, Where Alligators Sleep, and the novel Brown Bottle.

In 2012, he was a finalist for both the Gertrude Stein Fiction Award and the Still Fiction Award. His writing has been nominated for the Thomas and Lillian Chaffin Award for Excellence in Appalachian Writing, the Pushcart Prize, Best of the Net, Best of the Web, and was a finalist for the Queen’s Ferry Press anthology The Best Small Fictions 2015, guest edited by Robert Olen Butler. Other writing has appeared in the anthologies Degrees of Elevation: (Bottom Dog Press, 2010) and Walk Till the Dogs Get Mean(Ohio University Press, 2015), as well as numerous print and online journals.

CARTER MELAND, teaches American Indian Literature and Film courses for the Department of American Indian Studies. He received his Ph.D. in American Studies with a thesis that examined the role of tricksters in the works of contemporary Native novelists. His academic work has appeared in journals like American Studies, Studies in the Humanities, and Studies in American Indian Literatures. His fiction has appeared in numerous literary journals including Yellow Medicine Review, Lake, and Fiction Weekly.

DREW McWEENY, also known by his pseudonym Moriarty, is a film critic, screenwriter, and the former west coast editor of the Ain’t It Cool News website.

SCOTT SWAN, an American filmmaker and screenwriter best identified for his work with director John Carpenter. He is also the writer for Fear Itself segment “Skin and Bones” directed by Larry Fessenden.

ROBERT LEAVER, a writer, a musician, performance artist and sculpt artist. He has written for various magazines such as Esquire, High times, Field & Stream, as well as regional publications in the Hudson Valley. I’ve written scripts for films, one of which, an eco-thriller classic, The Last Winter, came out in theaters to great acclaim. He has collaborated on that script with Larry Fessenden. He has written stories, long and short, hundreds of songs, a few one act plays and many poems as well.

LARRY FESSENDEN, recently saw the release of a box set entitled The Larry Fessenden Collection from the label Shout Factory featuring new transfers of his four most celebrated films, No Telling, Habit (Nominated for three Spirit Awards), Wendigo (Winner Best Film 2001 Woodstock Film Festival) and The Last Winter (Nominated for a 2007 Gotham Award for best ensemble cast). Fessenden directed Skin and Bones for NBC television’s horror anthology Fear Itself and the feature film Beneath for Chiller films. He is the co-writer with Graham Reznick of the Sony Playstation videogame Until Dawn. He is founder and CEO of Glass Eye Pix, a production shingle which celebrated its 30th year in 2015, and he is the producer of revered genre fare such as The House of the Devil, Stake Land, I Sell the Dead and the audio series Tales from Beyond the Pale.

DONALD CARON, is a Montreal based illustrator who grew up in the suburbs, drawing and watching movies. He has worked as a commercial illustrator for Fantasia Film Festival and Spasm, as well as for the films Crawler, End of the Line, Under the Scares, and the video games Far Cry (3 & 4), Assassin’s Creed, and Splinter Cell. He has also worked on the comic series Vampirella and Heavy Metal.

TREVOR DENHAM, After serving in the U.S. Marines, Trevor enrolled at the Ringling College of Art & Design. Upon graduation, he found work in various horror magazines and thankfully fell in with Larry Fessenden and Glenn McQuaid, where he illustrated 4 posters for the Tales from Beyond the Pale radio series. He has created storyboards, pre-production film art, and comic books. Currently, he draws covers for Spacegoat’s Evil Dead 2 comic series and is getting fat eating lots of gumbo in Mobile, Alabama, where he lives with his beautiful wife, dog, and three cats.

MICHAEL KELLERMEYER, is the editor and illustrator for Oldstyle Tales Press, a craft publisher which specializes in annotated and illustrated anthologies of classic horror authors ranging from Blackwood, Stoker, M. R. James, Charles Dickens, and Edgar Allan Poe. Kellermeyer is an English professor who lives and teaches in Fort Wayne, Indiana with his wife, Kierstin, and a cozy library of 500 books.

GARY PULLIN, A horror fan since he could stick a tape into a VCR, “Ghoulish” Gary Pullin has grown into a monster-making machine. As Rue Morgue magazine’s original art director, the London, Ontario-born artist created the famous look of the publication, which currently hosts his art column, “The Fright Gallery.” Now a full time creature creator, his colourful signature style has graced numerous magazines, books and home video covers for Anchor Bay, MGM, Arrow Video and Scream Factory. He’s had his work featured in galleries across North America, created highly sought-after screen-prints for Mondo and created vinyl designs for Death Waltz Recording Co. and Waxwork Records. Gary’s created key art for various recent films, including The Babadook, Grabbers and Birth of the Living Dead. Both Gary and his art will be seen in the upcoming documentaries Twenty-Four by Thirty-Six and Why Horror?

BRAHM REVEL, has spent the first half of his life in San Francisco and the second half in New York City. As a result, he has no idea what a moderately priced apartment is. In that time he’s worked extensively in the film and animation industries, most notably sharing storyboarding duties for a time on The Venture Bros. In recent years he’s turned his attention squarely to comics, recently writing and drawing the Marvel Knights: X-Men mini for Marvel Comics. He’s probably best known (hopefully) for his creator owned series, Guerillas, from Oni Press, and he promises that “the new volumes are almost done and will be well worth the wait!” Currently, Brahm is en résidence at La Maison des Auteurs in Angoulême, France, eating baguettes and reminding everyone that his middle name is Jacques.

ISABEL SAMARAS, Known for lush and meticulously painted riffs on Old Masters that feature pop culture icons of the past, Isabel Samaras’ ribald images are woven with references to classic horror movies, ancient mythology, cherished TV characters, tribal societies, and childhood fairy tales. Magical realism and the forbidden fantasies of fabled characters frolic in a world where elusive desires become reality, re-imagining ill-fated journeys that turn into enchanted honeymoons. Her painted narratives, classical in technique and pop in content, often revolve around issues of making things end the way we wish they would. Exploring “What if?” and “Why not?” she brings human desires and foibles to fictional characters, studying the human condition through the eyes of popular culture by jamming old and new together in the visual equivalent of a mash-up song. Samaras’ work has been featured in Juxtapoz, Hi Fructose, The New York Times, as well as several books including her own On Tender Hooks, and the documentary films The Lowdown on Lowbrow and Newbrow: Contemporary Underground Art.

BRETT WELDELE, is an Eisner-nominated comic book painter and New York Times Bestselling Author. He has been published by nearly every major comic book publisher in the US, and is available in several languages around the world. Probably best known for co-creating the hit comic book The Surrogates, which was adapted into the 2009 film starring Bruce Willis. Brett enjoys working on his own projects like Spontaneous and The Light as well as commercial gigs like Halloween, Se7en, 28 Days Later and Southland Tales. His recent projects include working with Shrek producer Aron Warner on Pariah for Dark Horse Comics and Vampirella 1969 for Dynamite.

ADE BARRETT, Digital artist with years of experience in illustration, cover art and creating video game assets. He specializes in realistic figurative painting and stylized drawing.

GRAHAM HUMPHREYS, is a British illustrator and visual artist best known for producing film posters. During the 1980s, Humphreys worked with Palace Pictures, producing publicity material for films including Dream Demon, Basket Case, The Evil Dead, Evil Dead II, theNightmare on Elm Street series, Phenomena and Santa Sangre.

Humphreys has worked with The Creative Partnership since the 1990s and Tartan Films since the 2000s. He has been involved in films including Life is Sweet, Erik the Viking, From Dusk till Dawn, House of 1000 Corpses, and Party Monster. Other film work includes material for The Pervert’s Guide to Cinema and Into the Dark.

Humphreys’s graphic design for print media includes work published in New Musical Express, Vogue, Esquire, FHM, QX, Arena, Loaded,Junior and F-1 Magazine.

BRAD KUNKLE, Figurative painter Brad Kunkle merges realism, fantasy, and psychological depth in his glowing compositions of women in nature. After working exclusively in oil earlier in his career, he became interested in the possibilities of adding gold and silver leaf to his paintings, taking inspiration from Gustav Klimt. This resulted in works whose surfaces shimmer and shift with the light, and which seem to emit their own radiance. The women in his works are more than one with nature—they are nature itself. Bird of Paradise (2011), for example, is centered upon a female figure whose lower half is more peacock than human, with a many-eyed tail spreading out behind her. In other compositions, butterflies, birds, and leaves surround Kunkle’s otherworldly women in energetic swirls, as if their bodies are in the process of dematerializing into such delicate natural things.

HUGO SILVA, He is an actor, known for Witching and Bitching (2013), Paco’s Men (2005) and The Body (2012).

For more info click here

Sudden Storm: A Wendigo Reader Paperback – February 16, 2016

$30.00

- Paperback: 158 pages

- Publisher: Fiddleblack ltd; 1st edition (February 16, 2016)

- Language: English

- Product Dimensions: 12 x 10 x 0.5 inches

- Shipping Weight: 8 ounces