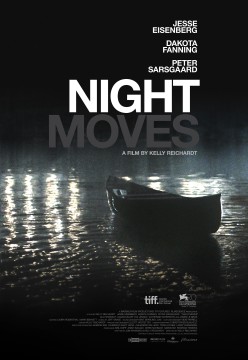

Night Moves

dir. Kelly Reichardt / wri. Jon Raymond, Kelly Reichardt (2013 112 min, Alexa, 1.78)

Jesse Eisenberg, Dakota Fanning, Peter Sarsgaard

Three radical environmentalists look to execute the protest of their lives: the explosion of a hydroelectric dam.

THE GUARDIAN

Peter Bradshaw 8/28/2014

The title of Kelly Reichardt’s Night Moves has a ghostly echo of Arthur Penn’s 1975 noir of the same name, which featured Gene Hackman as the private detective hunting a missing woman, and getting into a watery nightmare. There are traces of noir here, too, but distinctively mixed with something calmer, blanker, less obviously flavoured with genre. This Night Moves is like a suspense movie held in suspense: a thriller that behaves as if it is a gentle, indie-arthouse film concerned only with evoking the static beauty of nature. There can’t be many screen dramas in which a climactic fight between characters is accompanied with quiet, plangent pan-pipe music on the soundtrack, the sort that one generally hears in the reception at a hotel spa. And yet the film is gripping and disturbing.

Jesse Eisenberg, Dakota Fanning and Peter Sarsgaard play a trio of environmental activists: Josh, Dena and Harmon, respectively. Josh lives and works at a co-operative farm; Dena is his close friend – there may be a romantic entanglement between them – and Harmon is a slightly freaky ex-Marine of Josh’s acquaintance, with long hair, radical views and some rather picturesque vocab: he says “split” instead of “leave”. His character is another way in which this feels interestingly like a revival of American indie cinema of the 70s.

Enraged by the futile rhetoric of conventional environmental activism, they plan direct action: to blow up a hydro-electric dam, which is destroying wildlife. As Josh puts it, the dam is there “killing all the salmon, so you can run your iPod every second of your life”. Rich-kid Dena’s family is bankrolling the operation; she pays for the 1,500lb of ammonium-based fertiliser needed for the explosives and puts up $10,000 (£6,000) in untraceable cash to buy a cruiser, which they will turn into a huge floating bomb. They plan to sail up to the dam wall in the dead of night one weekend, set the timer, and paddle away very quickly indeed in a canoe. The craft’s name is Night Moves. Naturally, things do not go to plan.

This is not like The Dam Busters and neither is it like The Battle of Algiers. The film does not have the conventional narrative beats of a thriller, but neither does it obviously signpost the plot points of another, more interior sort of drama: the story of the activists’ apparent love triangle. The emotional tensions are there, but submerged. In many ways, it feels like Reichardt’s limpid film Old Joy from 2006, about two friends taking a hike in Oregon’s Cascade mountains.

What Reichardt is so good at is suggesting the long, slow nightmarish fallout of their eco-terrorist operation, the “denial” phase, the all-important aftermath in which it is vitally important that they go back to work on Monday morning, pretend to others and even somehow to themselves that nothing has happened. And because the movie does not behave like an action-thriller, it gives an eerily close and convincing sense of what this might actually feel like: the numbness, the sense of unreality, which in this case changes into a icy sense of horror.

These are three very closed and opaque performances: the direction does not offer up the film’s meaning easily. Eisenberg is never a very demonstrative actor, but here he really is very withdrawn, giving an impression of a guy who has learned to tamp down his emotions. Fanning’s Dena, too, is under control, again because she is aware of what is at stake and because she wishes to be taken seriously. Only Harmon, the ex-soldier, permits himself some swagger, some smirking, some indiscipline: it is another way of imposing status and authority.

It is almost as if the natural world, on behalf of which all this illegality and violence has been carried out, has imposed its own vast calm and placidity on the film itself. Yet something else is going on: Josh’s paranoia is creeping up on him stealthily. There have been tense moments in the film before this point – as Dena attempts to buy fertiliser from a farm store and when she and Josh get stopped at a police roadblock – and then an out-and-out catastrophe. But Reichardt manages to convey that nothing is so ominous and insidious as the way the world blandly carries on while Josh gets more and more tense, more locked into unspoken fear as his guilt closes in. His confidence in himself, in getting away with the operation, and in the notion that it was justified in the first place, are all withdrawing like a sea of lost faith. It is a very disturbing spectacle.

STAR TRIBUNE

Rob Nelson 9/26/2014

Not in many moons has a debate over a movie energized me more than the one that followed my recent screening of “Night Moves” with friends who found it problematic at best and irresponsible at worst.

To make a long story short, I’ll just say it was left to me to defend Kelly Reichardt’s indie eco-thriller (now widely available for streaming on demand) against charges that the writer/director grossly misrepresents radical activists and damages their cause when not simply boring the viewer to tears.

As in her acclaimed “Old Joy” and “Wendy and Lucy,” Reichardt here approximates the contemplative pace of Pacific Northwest life in addition to making nature into a major character. In “Night Moves,” the lush scenery is a doomed hero, to whose defense — arguably, anyway — comes a largely unsympathetic trio of young eco-terrorists who plot to blow up a hydroelectric dam in protest of technological progress. (Salmon will soon be extinct, one of them says, so that the masses can keep diddling with their smartphones.)

Dena (Dakota Fanning), a nervous trust-fund kid with a conscience, and Harmon (Peter Sarsgaard), a lethargically swaggering ex-con, display the sort of severely limited charisma that those allergic to activists could appreciate. But it’s Josh (Jesse Eisenberg) who, from his first moment on-screen, oozing pent-up rage, threatens to turn the movie into a portrait of political action as downright pathological.

An old slogan says that if you’re not outraged, you’re not paying attention, and Josh is nothing if not attentive — as well as depressed, selfish, misogynistic and more. An early scene where he stands in the back of a group of activists screening a woman’s film about environmental devastation types him as seethingly intolerant of good intentions while allowing Reichardt to pose questions of political representation that she refuses to answer definitively.

Do progressive-minded movies have an obligation to be inspirational at the expense of truth? Doesn’t a tragically fragmented subculture demand a polarizing treatment? What do you think?

I think discussion or even argument is what Reichardt wants more than mere approval. While I may never resolve my own issues with the movie (particularly its third-act twist), I applaud the filmmaker for the sort of political daring and devotion to ambiguity that would likely make her an outsider at the commerce- and agenda-driven Sundance Film Festival, whose programmers naturally passed on “Night Moves.”

I’d say this is a movie about alienation that, in the spirit of the boldest activism, isn’t afraid to be ostracized itself. You may beg to differ, and I’d say that’s the point.

WASHINGTON POST

Michael O'Sullivan 6/5/2014

“Night Moves” isn’t so much a thriller as thriller-ish. That’s not to say that the movie — which centers on a plot by a group of environmental activists to blow up a hydroelectric dam — disappoints. It’s a richly engrossing drama, so long as you understand that it’s aiming for the head, not the gut.

That means that the story builds up a powerful, almost unbearable level of suspense, only to refuse to release it in the end. Although that will surely let some viewers down, it will reward those who don’t mind leaving the theater with something other than tidy closure. This isn’t a movie where the good are rewarded and the bad are punished, but one that invites us to question what those labels even mean.

Much of the film’s first half is devoted to preparations for the bombing, which has been organized by Josh (Jesse Eisenberg), a humorless idealogue who lives and works on an Oregon farm providing produce to members of an urban agriculture co-op. Josh is almost sociopathic in his self-righteous fury about the salmon that have been killed by the dam just so, as he puts it to no one in particular, “you can run your iPod every second of your life.” Dena (Dakota Fanning), a dilettantish spa worker, is bankrolling the operation. Former Marine and ex-con Harmon (Peter Sarsgaard) — who seems in it as much for the explosion as for the message it’s intended to deliver — handles logistics.

It’s a group of odd bedfellows, and paranoia runs high, with no one really trusting anyone else.

As with her 2008 film “Wendy and Lucy,” director Kelly Reichardt holds a magnifying glass up to the threads of our fraying social fabric. For long stretches, we watch various members of the trio carrying out banal pre-bomb work, as if they were planning a potluck. Josh and Dena negotiate the purchase of a boat; Dena is sent to a farm-supply store to pick up 500 pounds of ammonium nitrate fertilizer that will fuel the blast; all three mix and pack the explosives, and then load them into the boat’s hull, which Josh has gutted of its furnishings. This kind of minutiae is hardly cinematic, yet it contributes to a mounting sense of dread.

The tedium is alleviated by occasional moments of high tension. When Dena is almost stymied in her shopping trip — she has to lie to persuade the farm-supply manager to sell her that much of a controlled substance without a Social Security card — it’s hard not to pull for her, even though we’re sickened by the thought of what she wants to do with it.

Reichardt’s neatest trick is getting us to care about three people who are about to do this dangerous, illegal — though ostensibly high-minded — thing. And then when it’s done, and the real-world consequences of their actions hit home, we feel the same sinking feeling — even betrayal — that they do.

“Night Moves” is really about the different ways in which the members of the group cope with those consequences. Sure, there’s some question of whether they’ll get away with it, and that propels the movie. But after a certain point, that doesn’t even matter. Responsibility, disillusionment and the corruption of principle are the film’s true themes, and it tugs at them relentlessly, pulling them up by their dirty, tangled roots. It’s a movie about environmental extremism, but it could just as easily be set in Congress or the Occupy movement.

Written by Reichardt and her longtime writing partner, Jonathan Raymond, “Night Moves” is not a chatty film. Arguments one way or another are few and terse.

When news of the dam bombing comes out, Josh’s boss succinctly dismisses it as meaningless “theater” that will change nothing. There are 10 other dams on the river that would have to be blown up to make a difference to salmon ecology, he says.

Whether he, or anyone else in the film for that matter, is right or wrong isn’t the point. “Night Moves” is about the difficulty of coming to terms with what lies downstream — just around the river bend and out of sight — from every little decision we make.

★★★★

ROGER EBERT . COM

Brian Tallerico 5/30/2014

Kelly Reichardt makes films so keenly in tune with the natural world that it seems appropriate that the director of “Meek’s Cutoff” and “Wendy & Lucy” would turn to the world of eco-terrorism for her newest thriller, the excellent “Night Moves.” Her story of three people caught in a web of mistakes and distrusts may first seem like a departure from her more character-driven dramas but, trust me, it’s not. “Night Moves” eschews traditional tension-building through plot twists and betrayals to focus on its characters, as Reichardt uses her increasingly impressive sense of composition and intuitive pacing to slow burn the audience into a state of anxiety instead of manipulatively pushing them there.

“Night Moves” is about three people itching to make a statement in a world in which technology has overtaken agriculture. Josh (Jesse Eisenberg), Dena (Dakota Fanning), and Harmon (Peter Sarsgaard) are going to blow up a dam. The first half of Reichardt’s delicately timed narrative sees the planning of the event; the second details the inevitable fallout. Reichardt and her writing partner Jon Raymond don’t weigh their narrative down with political rants or environmental messages. These are people who have had enough and feel that protests are no longer getting the attention their issues demand. That’s all you need to know. And that they’re going to take action.

As with all of Reichardt’s films, it’s more about the journey than the destination. As played by Eisenberg with more subdued detachment than usual (and perhaps more than the part called for, especially in the final act), Josh is a deliberate, patient terrorist. Eisenberg and Reichardt sketch him too organically to call him calculated but Josh is definitely the most deliberate of the three terrorists. Harmon, as perfectly captured by Sarsgaard in what ends up being a disappointingly small role, is more able to adapt to the situation. Sure, the waiter who recognizes him during part of their journey could be a problem. As is the fact that Harmon knows the guy from his time behind bars, which he failed to disclose. But it’s not a big deal. Josh is the one who needs every detail to fall into place; Harmon is the one who rolls with the punches. In between, we have the lovely Dena, closer to Harmon in her willingness to work with what she’s given, such as in a masterfully tense scene involving the purchase of fertilizer, but clearly drawn to the brooding, purposeful Josh.

Reichardt builds tension through the cumulative impact of seemingly minor moments. What will be the downfall of this trio? Will it be the aforementioned fertilizer scene? Will it be one of the people that they seem to always inadvertently run into as their plan materializes? Will one of the three leads destroy their plan or betray the other two? As one might expect who knows Reichardt’s films, the director avoids easy thriller clichés or even answers. Major events take place off screen. A key one in the final act is shot with close-ups of eyes and feet. In “Night Moves,” as in all of Reichardt’s films, it is not just the incident that matters but its build-up and follow-through. And, again, she makes a decision with her ending that will frustrate some with its ambiguity but thrill those willing to accept her desire to work more in ellipses than periods.

It should also be noted that “Night Moves” is a gorgeously composed film. Reichardt’s emphasis on the natural world in all of her films has led to an under-appreciation of her skills as a visual artist. As shot by the increasingly impressive Christopher Blauvelt (who also shot “Meek’s Cutoff” and took over for Harris Savides after his passing on “The Bling Ring”), “Night Moves” is one of the most literally dark films you’ll see this year. So much of it is lit by on-set sources like the dash of a car, the lights of a boat, the dim light of the moon, etc. This is not one of those awful blue-lit movies in which the moon casts a turquoise hue that one could read by in the real world. It is a film about people who move in darkness, willing to take chances for what they believe but only under cover of night.