Indiewire article ponders the state of indie horror, pits SpectreVision against Glass Eye Pix (unnecessarily) and wraps up with a sentimental finish involving child murders and Tales from Beyond the Pale:

Two years ago, the fan site Couch Cutter wrote a piece called “Fuck You, an Open Letter to the Horror Community.” Though two years is a lifetime in the internet age, the piece’s sentiments are still profoundly relevant right now. The anonymous author blames the fans for the plethora of bad indie horror movies and the apparent lack of good ones; not mincing words, one articulate commenter opined, “99% of current horror movies suck balls.”

In a recent Writer’s Guild profile, John Carpenter disagreed. “Horror today is pretty much like it always has been,” he said. “Ever since the beginning of cinema, it’s been with us. Most horror films are awful, some are good and there are a very, very few that are really good. It’s always kind of been that way.”

Two years ago, the fan site Couch Cutter wrote a piece called “Fuck You, an Open Letter to the Horror Community.”Though two years is a lifetime in the internet age, the piece’s sentiments are still profoundly relevant right now. The anonymous author blames the fans for the plethora of bad indie horror movies and the apparent lack of good ones; not mincing words, one articulate commenter opined, “99% of current horror movies suck balls.”

In a recent Writer’s Guild profile, John Carpenter disagreed. “Horror today is pretty much like it always has been,” he said. “Ever since the beginning of cinema, it’s been with us. Most horror films are awful, some are good and there are a very, very few that are really good. It’s always kind of been that way.”

Dissenting skepticism hasn’t dwindled since Couch Cutter’s article. Modern indie horror is still unfairly marginalized as being universally awful, but no one’s going to argue that modern indie horror films are actually universally good, either: for every “The House of the Devil” or “The Lords of Salem” or “V/H/S,” there’s ersatz schlock — as opposed to genuine schlock — like “Texas Chainsaw 3D,” “Argento’s Dracula 3D,” or “V/H/S 2”; for every innovative idea (the brilliant “Berberian Sound Studio”) or successful reimagining (“Evil Dead,” “Maniac”) there’s a new “Carrie.”

The best recent horror films are self-aware and possess a keen understanding of horror history. “You’re Next” shows an awareness of the films it’s channeling, while “We Are What We Are” is an astute, deceptive foray into “Texas Chainsaw” territory with similar high-brow aesthetics. Good horror can be smart (“Cabin in the Woods”) or aware of its own stupidity (“My Name is Bruce”), or it can hide its smarts behind a guise of stupidity (“Slither”).

But many figures in the horror community feel that the genre is being held back by a lack of historical awareness. “I have to remind young people that horror films existed before 1980,” Ryan Turek, proprietor of the site Shock ‘Till You Drop. He was moderating a panel on the current state of indie horror at the four-day-long Stanley Film Fest in Estes Park, Colorado, where Stephen King once dreamed up the idea for “The Shining.”

The festival, only in its second year, was inadvertently pervaded by this question regarding the current state of indie horror. It acted not only acted as a microcosm of the eclectic tastes of modern horror fans (whose ages ranged from underage to retirement), it also encapsulated the complicated, multi-faceted world of filmmaking in general. Here are some of the key takeaways.

It’s Harder Than Ever to Make Great Horror

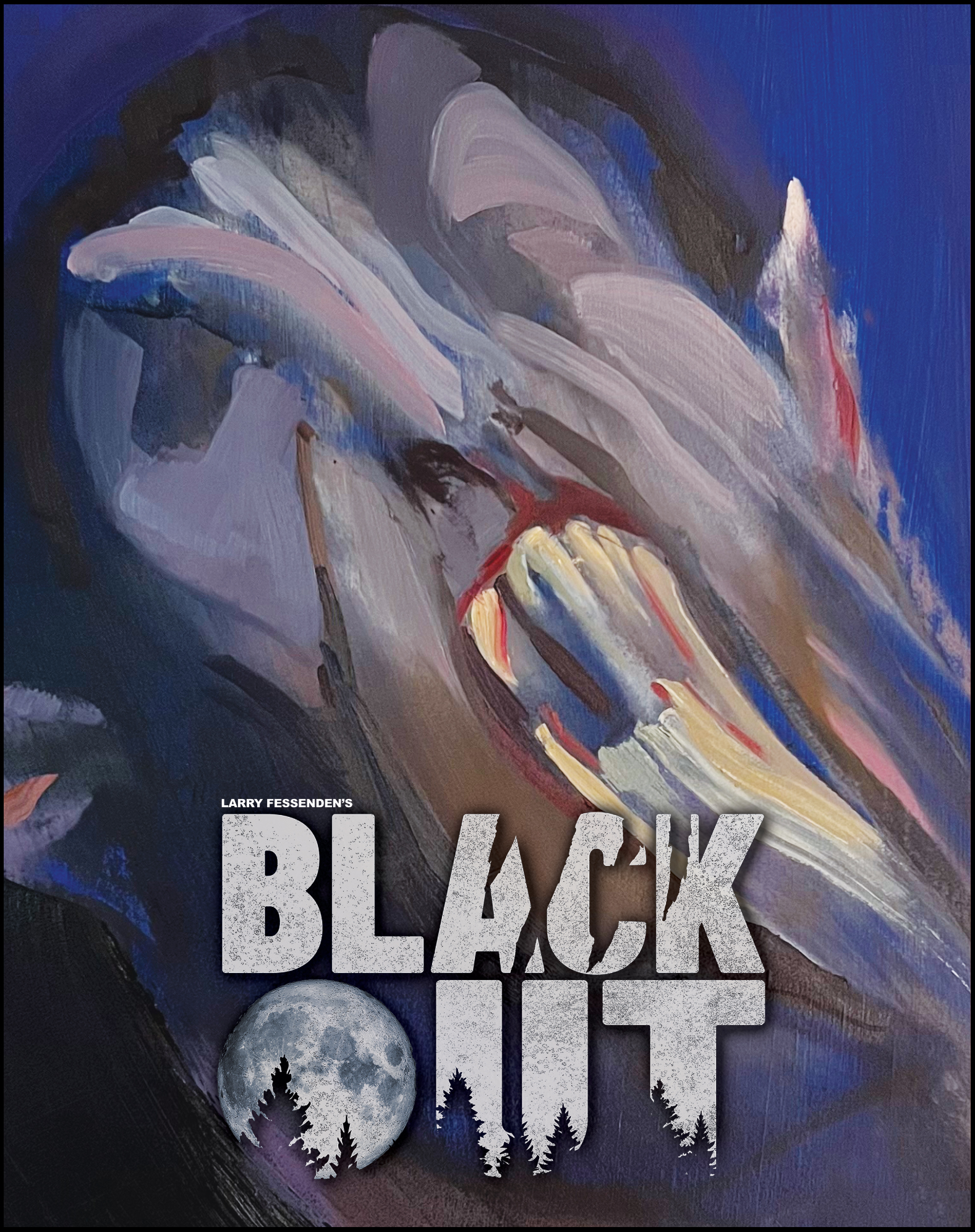

Many horror filmmakers at the festival expressed frustration over the creative and business sides of horror filmmaking today: like a throbbing wound that won’t heal, the queasy notion of money — who has it, who needs it, how you get it and what you do if, inevitably, you can’t get it — came up in each panel. According to director/writer/producer/actor/whiskey connoisseur Larry Fessenden (“Habit,” “The Last Winter”), the indie filmmaking economy was much better seven years ago. Producers were more willing to take risks. The genre used to be the star that caught the gaze of producers; now a cast rife with prominent names is a prerequisite.

“I consider ‘real money’ to be anything over a half million dollars,” Fessenden said. “The New York Times will call a Fox film ‘micro budget’ when it costs 1, $1.5 million. That’s not micro budget.”

Studios Aren’t the Answer

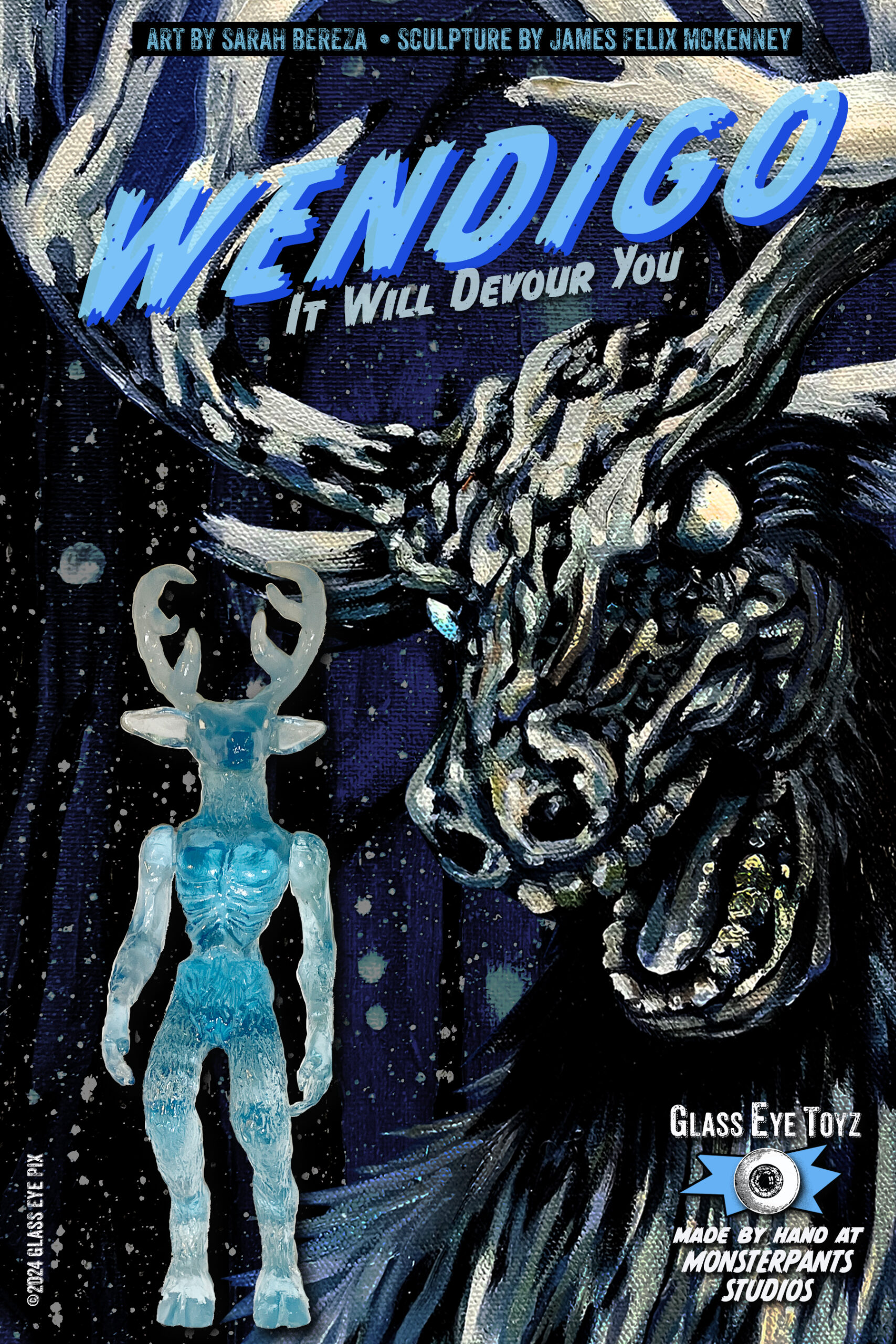

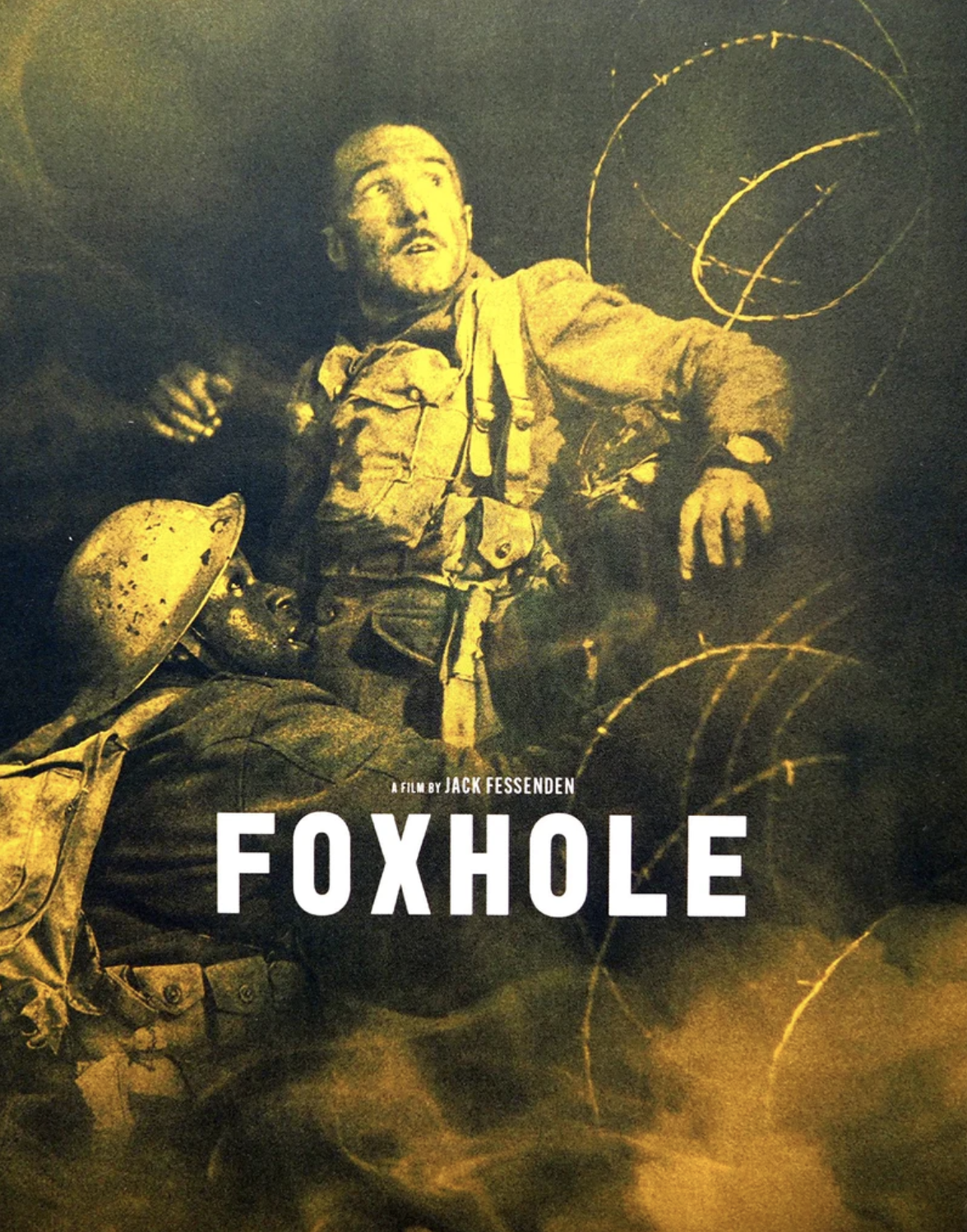

Ti West, who began his career as an apprentice working for Fessenden’s company (or “community,” as Fessenden calls it) Glass Eye Pix, has run into his share of turbulence in his dealings with producers. His 2005 debut feature “The Roost” cost around $50,000, recalled Fessenden. Four years and an accruement of fans later, West’s budget swelled to $1 million for “The House of the Devil.” The film has become a cult-favorite, and its languid pacing and tumultuous final act made West a brand with a fervent following. (West credits the film’s success to the “awesome poster” by Neil Kellerhouse.) But West’s brief triumph meant studio offerings would pour in—that is to say, generic, derivative would-be blockbusters replete with what West calls “cool shots”: slow-mo punches with facial flesh flying; bodies enveloped by shattered-glass nebulas, plummeting to the ground; cameras following the tracery of bullets, in slow-mo, of course, and so on.

“This sounds selfish, but I make films for myself,” West said. “I don’t have an audience in mind when I make my films. I make the films I want to make.”

West isn’t one to bemoan modern horror films (as long as there are auteurs, he said, there will be good horror films—you just have to find them), but he described the invasive nature of sticky-fingered producers as “traumatic”; if people are going to interfere with his vision, he won’t bother to make a film with them.

West and Fessenden likened the erosion of the middle-ground budget in indie films to the eradication of the American middle class. “You have micro-budget films and you have ‘The Avengers,'” said West. “Nothing in between anymore.”

VOD Isn’t the Enemy

Fessenden’s long career has seen the rise of indie filmmaking and the advent of online streaming and video on demand; VOD is still tainted by a stigma, blamed for the demise of theatrical releases, but every panel thoroughly addressed the VOD vs. theatrical-release argument, and feelings seemed universally happy regarding VOD.

“VOD is necessary,” said James Shapiro of Drafthouse Films. “The last really successful limited theatrical release indie [horror] was ‘Paranormal Activity,’ and that was a long time ago.”

Drafthouse’s “The ABCs of Death” made about $1 million during its first weekend via VOD; theatrically it brought in only $20,000.

It’s a struggle for distributors to afford the risk of niche films, but VOD allows them to release films that may have smaller audiences without going bankrupt. West, whose films are distributed by Magnolia Pictures, endorsed the prospects of VOD, which may strike some fans as ironic, as West was deemed a “retro” filmmaker (an admittedly useless moniker, he admits) after his “The House of the Devil,” set sometime in the Reagan era and filmed with anachronistic equipment, was a sleeper hit.

“I love to see my films up on a big screen,” he said, “but there aren’t many theaters willing to take a risk on an indie that’s slightly left-of-center. Who knows if my film is going to play at Estes Park? If it’s released on VOD, I know that it will play in Estes Park, and more people can see it.” That’s an especially astute observation in relation to the horror genre, which has a very specific fan base spread across the country (and beyond).

If Nobody Else Will Make It, Make It Yourself

SpectreVision’s situation is a little different. SpectreVision is a production company founded by Elijah Wood, Daniel Noah, and Josh C. Walter that focuses on unique genre films, regardless of filmmakers’ track records or potential audiences. The triumvirate produces films that are generally low-budgeted— “Toad Road” is a genuine micro-budget feature, shot wherever was opportune, with non-actors found via Myspace, on home-quality cameras; but they’re willing to run the risks of low-profit, high-art films. They haven’t run into any major problems yet.

“We don’t have a big daddy lurking over our shoulder,” said Daniel Noah, emphasizing that maintaining creative control is vital to their films. “Ultimately, our role as producers in the most general sense is to protect and support the vision of the artist,” Elijah Wood said. Noah subsequently likened SpectreVision to a parent, and the films they produce being their children, and Walter compared their role to that of a music producer.

“Sometimes you sense real quick that you just need to get out of [the director’s] way,” Noah said.

“And sometimes you need to say no,” added Walter. “You need to send your kids to bed.”

Wood also expressed skepticism regarding over-hyped notions of evil producers sapping the essence out of indie filmmakers: “We haven’t seen a lot of that,” he said. “But I’m sure it happens, especially with more corporate producers.”

While not immune to the difficulties that plague indie horror filmmakers, SpectreVision, which has a slew of films opening this fall (including the incredibly-hyped Iranian vampire western “A Girl Walks Home Alone at Night”), are functioning in a different realm than Glass Eye Pix. Whereas Fesseden describes himself as “old school,” SpectreVision may represent a bright future for indie horror—a gleeful response to those who bemoan its current state.

“One look at the Sundance lineup shows you that horror is bleeding out of the midnight screening slot,” said Elijah Wood, to rousing applause.

The aforementioned schism between creative and financial that trips-up many filmmakers isn’t a huge factor for SpectreVision. The trio succinctly summarized their mission: they want to be a “brand that that seeks artists with unique perspectives.”

It Takes a Village (Of the Damned)

“There’s a real sense of community in indie horror,” Wood said. “There’s support, and we’re all in it for the same reasons: to make good films and support the artists.”

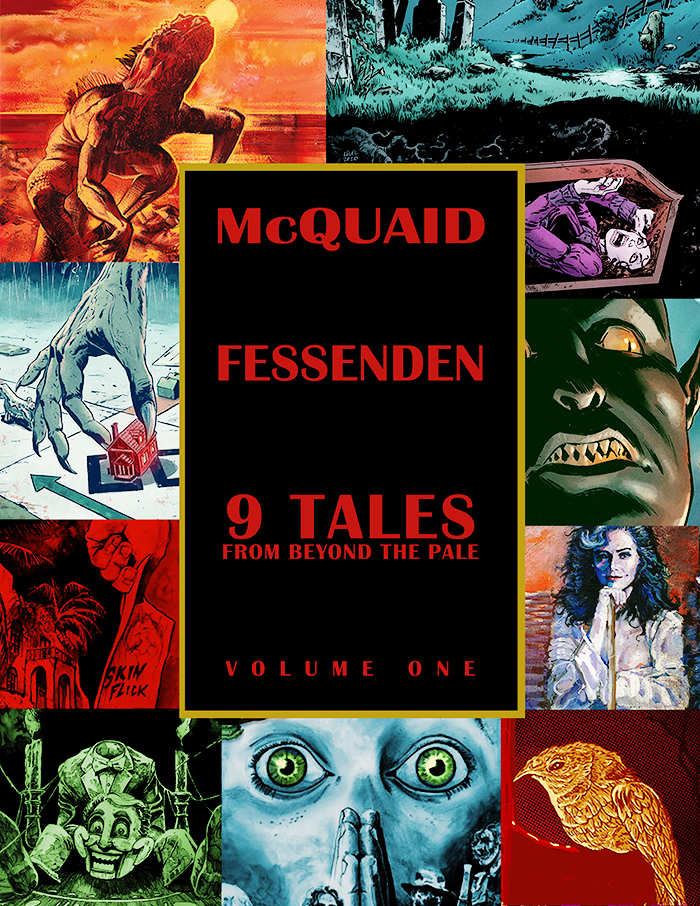

At this point the trio abruptly broke away from the interview to congratulate the voice actors who had just performed a live radio play called “Tales From Beyond the Pale,” which included Larry Fessenden, AJ Bowen, and Fangoria managing editor Sam Zimmerman. It was a perfect horror nerd moment: sitting on blood-red seats in the Historic Park Theater, the oldest functioning movie theater west of the Mississippi, waiting for a 35mm screening of “Who Can Kill a Child?,” the old school and the new were, however briefly, together, and the current state of indie horror looked to be doing just fine.

Add a comment