“’I suspect that the less you know about me, the longer you’ll stay interested.’

Habit: [hab-it] noun, 1) an acquired behavior pattern regularly followed until it has become almost involuntary; 2) a dominant or regular disposition or tendency; prevailing character or quality; 3) addiction, especially to alcohol or narcotics

The vampire of legend is eternal, and its cinematic brethren are equally durable and widespread. Even before the post-millennial pop culture phenomena of Twilight and True Blood (among others) but especially in their wake, it’s refreshing and rewarding to encounter an undead feature possessing a genuinely grounded and unique interpretation.

As Larry Fessenden’s Habit (alongside George Romero’s Martin, Abel Ferrara’s The Addiction, and Michael Almereyda’s Nadja) shows, it’s not just about bringing the vampire into contemporary settings. Since the 1930s, the silver screen has hosted an array of “modern” bloodsuckers preying upon hip and sensible disbelievers. What’s often missing is a true sense of personality, vision, and passion, and it is here that Habit delivers with both barrels. No other artist could have made this picture; Fessenden’s DNA runs through the sprockets at 24fps and his fierce integrity elevates it above other generic toothy thrillers. Like all great fanged flicks, the fantasy exists as an allegory for something deeper—intelligent and heady material perfectly interwoven with horror trappings such that the subtext eases into our brains unperceived…where it can burrow and grow.

Sam (Fessenden) is introduced recovering from the sudden death of his archeologist father, but it’s clear that life has not been going well for some time. His longtime girlfriend Liza (renowned solo artist Heather Woodbury), troubled by his general aimlessness and excessive drinking, has recently moved out. He manages a bar/restaurant, but this is clearly not his passion. In fact, passion is decidedly missing from Sam’s world; in its place a yawning disconnectedness into which he pours nightly gallons of booze. He has few interests or friends, and those that he does have, like Rae (Patricia Coleman) and Nick (Aaron Beall), cluck disapprovingly behind his back. At one point, he refers to himself as “committing suicide on the installment plan.”

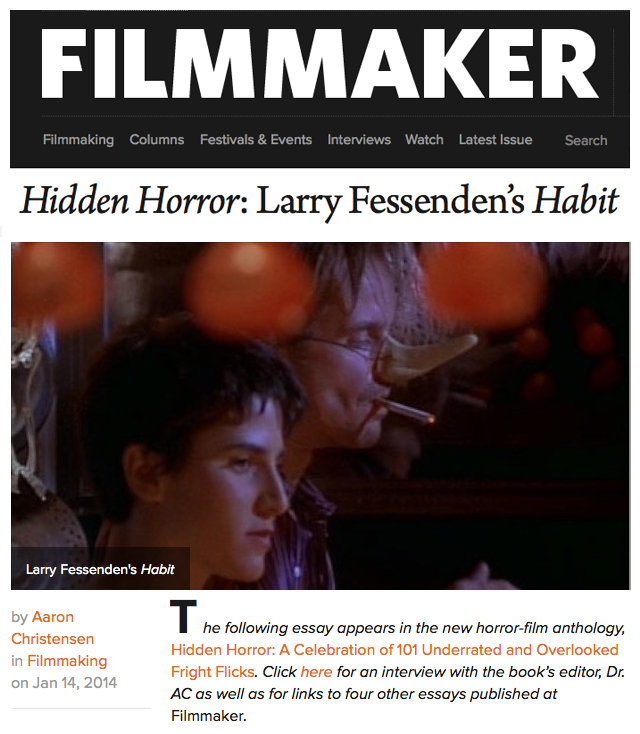

Into this bleak existence enters Anna (Meredith Snaider, magnetic and sensual in her only screen role), a classy and together mystery gal who sets her unassailable gaze on Sam during a Halloween party. Before long, the two are enjoying public sexual assignations, encounters that end with him alone—bewildered and bleeding—come the morning hours. As their relationship blooms, our hero grows more sickly and wan, leading him to wonder about his paramour’s true nature.

What is Habit really about? Vampires? Alcoholism? Addiction? Urban disconnectedness? The oppressive, nameless fears of metropolitan life? Sex? Disease? Or is it about Mars, Venus, and the great chasm between the sexes? The answer is yes to all of these and more. Via email, Fessenden explained that he was attempting “a traditional horror story told in a stark, naturalistic way, with heavy life or death themes in the presence of the supernatural. I love looking for new truths in old clichés.”

Tweaking of traditions is key to his approach. Repeated references are made to the classic vampires of old: Anna’s seeming aversion to garlic, not entering Sam’s apartment until invited in, only appearing during sunless hours, etc. Naturally, Stoker’s Dracula is cribbed from the most, introducing not only a ghost ship sailing into New York’s harbor (a la the Demeter’s ill-fated voyage from Transylvania), but also a Lucy Westerna character—rocker/waitstaff Lenny (Jesse Hartman), the first of the vampire’s unfortunate victims.

Revisiting a long-form video project from Fessenden’s NYU undergrad days, Habit was shot over the course of three months for a paltry $60,000. Being that the writer/director/editor was also onscreen for nearly every setup, a communal responsibility for the project was quickly cultivated, with DP Frank DeMarco and producer Dayton Taylor covering a multitude of roles. Even so, the script is wildly ambitious, with wolves running loose in Central Park, a shattered fire hydrant showering an auto accident’s aftermath, late night strolls passing racy photography shoots (a restaging of Nelson Bakerman’s “Wall Street Nude” project). There is a desperation sensed on both sides of the camera; Sam the character wondering if he will live through this relationship, the tiny crew wondering if they will complete the film—or even that night’s shoot. Watching Fessenden run naked through the midnight streets or hang from a sixth story apartment complex window, we feel the passion of a deeply committed artist inside the skin of a vulnerable character out of his depth. We find ourselves rooting for both, on completely different levels, at exactly the same time.

Fessenden’s inherent scruffy likability, highlighted by a missing front tooth, makes for an excellent wounded protagonist. His Sam is clearly intelligent, witty, charismatic, but we instantly recognize him as that friend who could be anything if he would just pull himself together, the one we root for even as we maintain an arm’s length to avoid being dragged down if/when he goes under. The film possesses a certain timelessness (excepting the diner scene’s giant mobile phone) and as a writer, Fessenden is much more concerned with character than plot. Some might complain about the leisurely pace, whether we really need to see Sam cleaning out the litter box or pour his two cups of coffee into a saucepan for reheating, but each scene has its rewards, especially upon repeat viewings. If there is a scene that deserves excision, it’s the unnecessary third-act confrontation between Sam and Nick, lousy with on-the-nose discussions of whether or not Anna is a vampire (the only time the word is used) and needless exposition about Sam’s financial status. It’s a rare misstep, but it’s a doozy.

As the mystery unfolds in Fessenden’s deceptively mundane fashion, several moments rich with possibilities and ambiguity emerge. One shining illustration is when Sam visits his late father’s historical society to receive a posthumous award: while Sam is talking to our ostensible Van Helsing character, Mr. Lyons (Lon Waterford), we see Liza enter the frame but in the reverse shot she miraculously becomes Anna. The surprised expression on Lyons’ face is open to interpretation: Did he see her transform? Does he know Anna from before? (Likely, since he later calls Sam wanting to talk about her.) What is the strange totem Anna gives to Sam? Why does the assembled group take such an interest in it? Where did she get it? Did she have something to do with Sam’s father’s sudden demise? Or is Sam imagining all of this?

Inside the head of a potentially unreliable narrator, we often wonder whether what we’re seeing is true (“is she or isn’t she?”) or just Sam’s potentially addled perception/fantasy of events. Fessenden tweaks the equation even further, allowing us to eavesdrop on an intimate nighttime conversation between Anna and Rae. This shaded viewpoint continues throughout, right down to the brilliantly ambiguous final shot as Tom Laverack’s aching acoustic tune “Mystery” shatters our sensibilities and our hearts break at a struggle lost. Then, in the blink of an eye and a shift of a lens, everything is upside down. Is it true, to paraphrase Joseph Conrad, that we all live—and die—as we dream…alone? That Habit ends on a tragic note is undeniable. What remains thrillingly unclear is the nature of the tragedy.”

Check Aaron Christensen’s essay out at Filmmaker Magazine and get a copy of Hidden Horror: A Celebration of 101 Underrated and Overlooked Fright Flicks here.

Add a comment