by JOSÉ TEODORO, April 15, 2024

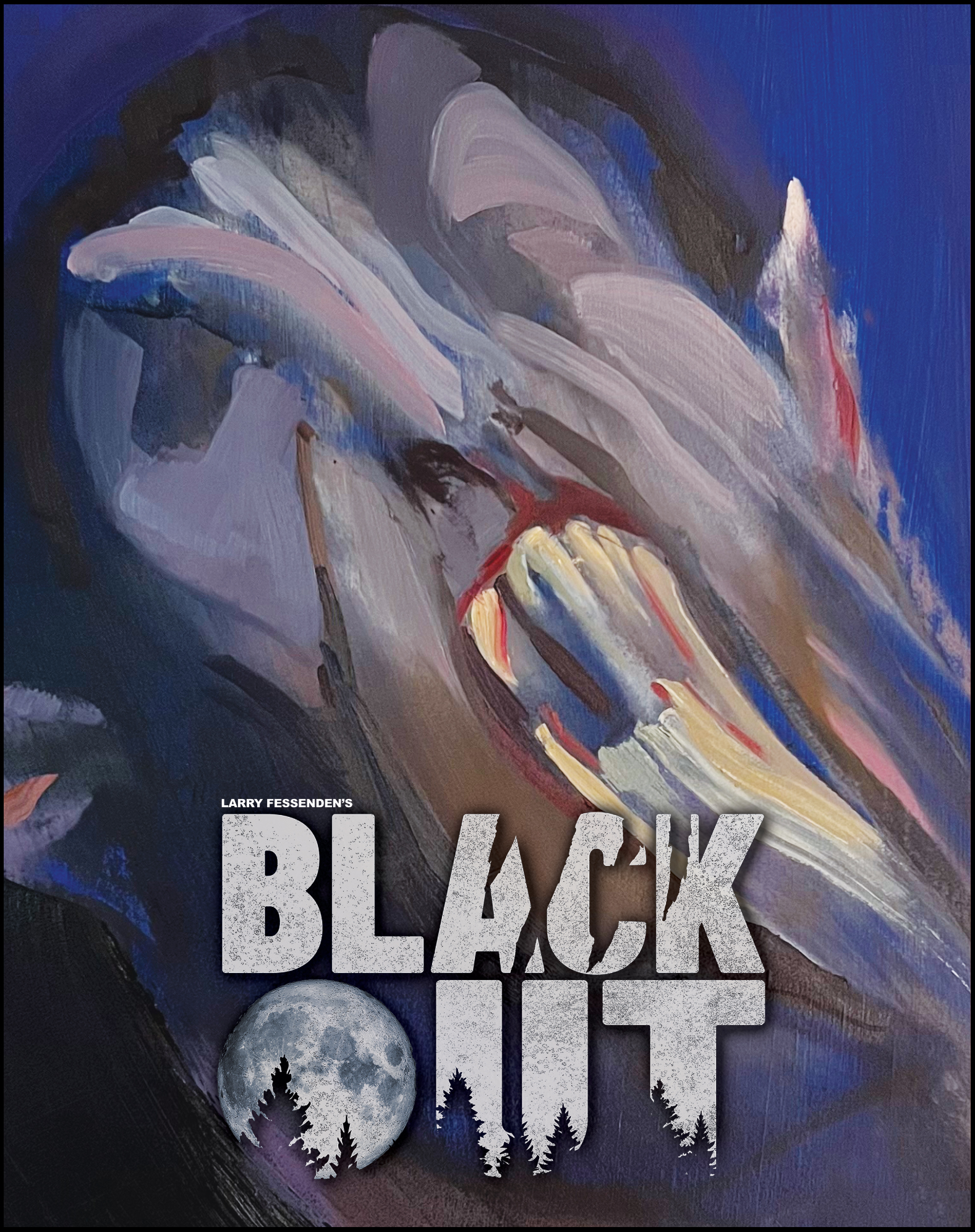

The premise, like the ambient air of fatalism, owes as much to film noir as it does horror. A man wakes in a place he can’t remember arriving at, his body bearing the ravages of some misadventure, his memories a dense fog yielding no clues save a lingering sense of grave culpability. His waking life is likewise rife with a sense of closure and entropy: he’s started to abuse alcohol, he’s lost the woman he loves, he’s quit his job, and he’s struggling with unhappy truths about his recently deceased father. The man is a painter, and his works are slowly becoming sites of revelation. Despite bouts of amnesia, he knows in his gut that for the past three months, he’s wreaked some terrible violence upon innocent people. And he’s resolving himself to the understanding that there is only one way to bring all this chaos to an end.

Writer/director/editor/producer Larry Fessenden is a special filmmaker, rare in his commitment to forging independent, modestly budgeted genre films, steeped in tradition, that also explore possibilities of style, engage with the world in the present tense, and maintain a dogged sense of empathy for his characters, even if the majority of them are absolutely doomed. Blackout is a paragon of this approach, renovating the werewolf story by, ironically, going back to its roots, making several overt gestures of homage to 1941’s The Wolf Man, such as naming the town where the story unfolds Talbot Falls, Talbot being the name of Lon Chaney Jr.’s protagonist, who indeed falls perilously after being afflicted with a disease that renders him a subhuman killer. Charley (Alex Hurt), Blackout’s protagonist, seems like a nicer guy than Chaney’s creepy attempted cuckolder. Convinced that he’s responsible for a series of grisly murders, Charley devises a plan for his own extermination that will double as a public exposé of a local developer’s corrupt business practices and xenophobic scapegoating—despite the fact that this exposé will also tarnish Charley’s father’s legacy.

Fessenden fills the margins of this existential monster movie with vestiges of contemporary working-class disenfranchisement and rising tensions around race and migration, labor exploitation, and environmental decay. At its best, Blackout addresses these issues not through preachiness but rather through character development and attention to the everyday: the way the camera will linger on a worker going about his job as a scene draws to a close, the cheerfully cynical comments made by a motel proprietor, or the delicate manner in which a Latin police officer addresses an angry white mob. All such moments are elevated by an excellent supporting cast, which includes such familiar players as Marshall Bell, Kevin Corrigan, and the great James Le Gros. The film’s foreground, meanwhile, closely monitors Charley’s subjective experience, with Fessenden drawing primarily upon two rich resources: a series of unobtrusive, hauntingly beautiful, rhythmically alluring animated sequences, and Hurt’s wounded eyes, physical expressiveness, and almost palpable interiority. Regarding the latter of these elements, the film also benefits from a third, meta element: Blackout, like The Wolf Man, is in part a father-son story, and Hurt is the son of William Hurt, whose image becomes a key to the film’s backstory. The younger Hurt’s performance plays as a palimpsest of, on one level, his own ample craft, charisma, and life experience and, on the other, numerous echoes of his father’s unmistakable screen presence. (There’s also the fact that the film’s first depiction of Charley’s transformation, a very cool sequence in which we get to watch a werewolf crash a car, can’t help but remind us of scenes of Hurt Sr.’s simian regression in Altered States.)

Blackout is also enriched by echoes of its immediate predecessor and companion piece, Fessenden’s 2019 film Depraved, which explores core components of the Frankenstein story in a context riddled with 21st-century anxieties. Both films literally dovetail in a manner that’s clever and poetic, and they share several themes, as well as plots that hinge on the protagonists’ gradual emergence of memory. It has to be said that they also share a narrative structure that feels one act longer than you expect, at least one dopey death scene, and a fair bit of corny, hard-boiled, exposition-heavy dialogue that’s somewhat redeemed by a sense of knowingness on Fessenden’s part—a kind of curational approach to cliché, along with, again, Fessenden’s deep empathy and affection for his characters. These are horror films with heart. Genre maniacs can rest assured that these are also horror films with plenty of merciless savagery: tremendous care is invested in selecting and staging arresting moments of action, spookiness, and gore. Blackout is a tale of heartbreak, justice, responsibility, and the potential terror of true self-knowledge—and whoever makes it to the end in one piece is largely the product of sheer, incomprehensible providence.

Add a comment