By Ryan Bradley for the New York Times Magazine

Ryan Bradley is a writer in Los Angeles. Over the course of a few weeks, he interviewed Ti West several times, as well as many of West’s longtime friends and collaborators.

Martin Scorsese, a fan of West’s, wrote to me that he thought each film in the trilogy represented a “different type of horror, related to different eras in American moviemaking.” The first, “X,” is “the ’70s, the slasher era”; “Pearl” is “’50s melodrama in vivid saturated color; “MaXXXine” is “’80s Hollywood, rancid, desperate.” They are, Scorsese wrote, “three linked stories set within three different moments in movie culture, reflecting back on the greater culture.” By smuggling thoroughly modern ideas into films that were also steeped in the aesthetics of the past, Scorsese thought, West had done something bold and thoroughly cinematic.

…

West grew up in the woodsy suburbs of Wilmington, Del., near the Bidens and a small private school called Tatnall, which he attended from kindergarten through 12th grade. The filmmaker and video-game writer Graham Reznick went there, too, and met West when they were in kindergarten. First they drew comics together; later they made the sorts of dumb films boys make, blowing up army men with firecrackers, recording it on a Hi8 camcorder. By their teens, they’d immersed themselves in their local video store, drawn to movies that seemed to them to exist in the same visual universe as what they had been getting up to in the woods — things like Peter Jackson’s “Bad Taste” or Sam Rami’s “Evil Dead,” scrappy films where you could practically see the guy holding the camera and deciding where to point it.

…

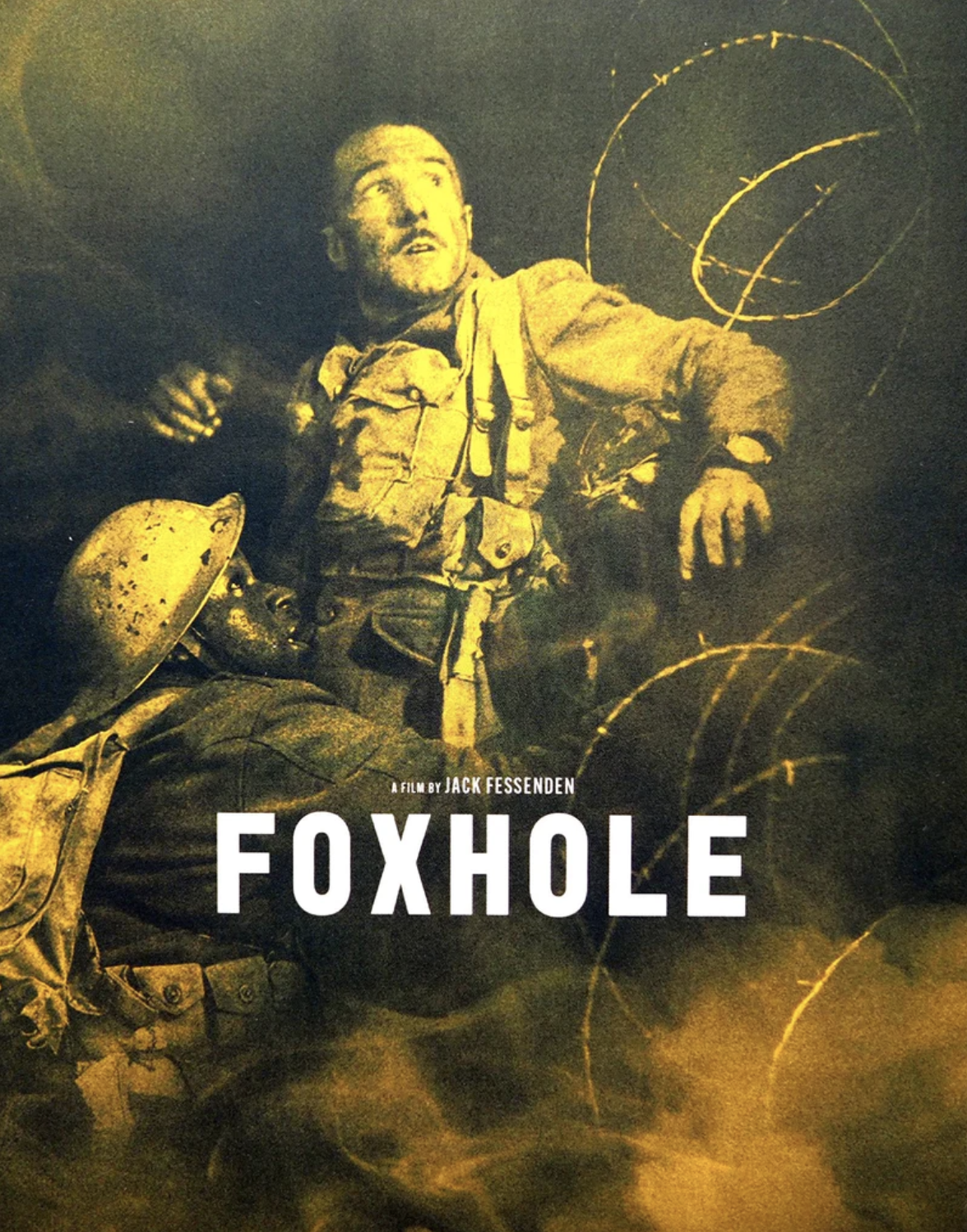

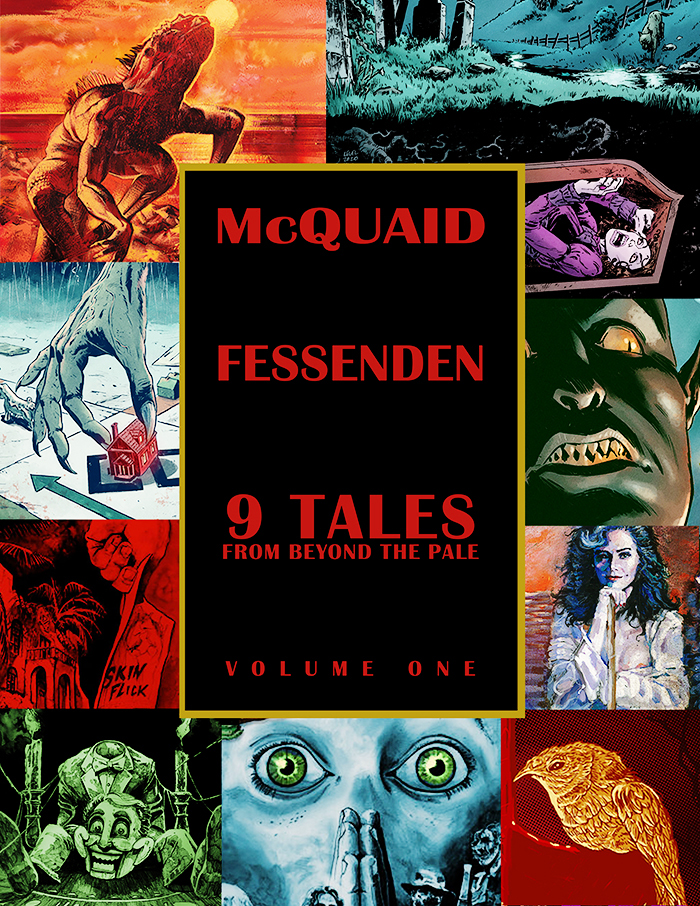

In 1999, West and Reznick headed to New York City — Reznick to N.Y.U. and West to the School of Visual Arts, where he lucked into a class taught by the filmmaker Kelly Reichardt. She is, West says, “very much responsible in many ways for me having a career.” In high school, he saw a movie called “Habit,” made by and starring Reichardt’s friend and frequent producer Larry Fessenden. Reichardt floated the possibility of having Fessenden come in to talk to her class, but it kept not happening, and West kept bugging her about it, and finally, West says, “she was like, dude, here’s his number. Just go meet him.” West did. And when Fessenden needed an intern, Reichardt recommended West.

“Now, Larry will tell you the story that I used that internship to duplicate copies of my short film to send to film festivals, and he’s not wrong,” West told me, but when I asked Fessenden about this, he just laughed and said what he really remembered was taking West aside: “I said, ‘Listen, kid,’” — here he put on a mock showbiz voice — “‘when you finish with college, if you ever want to make a feature film, you come back to me, eh?’” In Fessenden’s telling, West showed up in his office something like three days after graduation. “And the thing that really shows you what’s so strategic and smart about Ti — he didn’t come in with one dream project. He came with, like, four different log lines.” One even had an environmental angle, which he knew Fessenden would be a sucker for. Fessenden greenlit the idea that day.

…

West made several, often for very little money, and usually — in part because he is an only child and has trouble giving up control, but also because it’s cost-effective — he wrote and edited the movies too. One, about a trio of hunters who fear that they are being hunted, he made for about $10,000 in the Delaware woods. Another, about two friends investigating hauntings in a creepy old inn, was inspired in part by the creepy old inn he and the crew stayed in while making a different film entirely. The result, “The Innkeepers” (2011), was the first West film to catch Scorsese’s eye; after seeing it, he told me, “I thought: OK, I want to see everything this guy does.” The film reminded him of the work of Val Lewton, who was put in charge of RKO’s “horror unit” in the early 1940s and given a simple mandate: The films had to be under $150,000 and 70 minutes, and the studio heads would pick the titles; otherwise he could do what he wanted. The films he oversaw, starting with “Cat People” in 1942, were atmospheric and psychological, the tonal opposite of the screamy monster movies put out by Universal at the time. The amazing thing about “The Innkeepers,” Scorsese said, was that “you could eliminate the ghost story and the film would work without it, which echoes the way Val Lewton made his films: He always made sure that the core story had to stand on its own, apart from the supernatural elements.”

To Fessenden, it is an understanding of pacing — like West’s determination “to both frustrate the audience and then reward them” — that really ties together talent. “It’s also something you can only do if you’re defiantly independent,” he said. “Because, of course, in our blockbuster, Hollywood fare, everything is basically sort of commodified, and there are no challenging cinematic ideas because it’s all about the three-second cut.” I told him I was interested in what Reichardt made of West’s work, but he said she didn’t really watch new genre movies. He did, however, offer up a common thread between the two filmmakers, particularly in West’s early work. “I would argue — and this is maybe the whole point — they’re both interested in the texture and the timing, the slowing-down of time,” he said. “Now, Ti’s recent film is more bombastic, of course. But, at its core, the reason he’s known as a slow-burn guy is there’s a tremendous attention to everyday details. Ti’s build dread. Kelly’s, she builds maybe more like empathy. But there’s a similar thing going on.”

Add a comment