Here is a brief sampler set to Music:

But the truly intrepid will visit the site and

give themselves over to this time-based entertainment:

ICRAWLHOME.com

Here is Fessenden’s recollection of the project:

Notes from a wing man

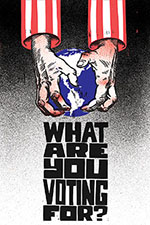

For a couple of years Robbie Leaver and I were writing scripts together, our collaboration was fruitful and robust. I dare say we wrote some fantastic scripts I’m still fighting to get made. When we allowed ourselves digressions from the work Robbie told me he wanted to crawl somewhere in protest against something, he wasn’t sure what. He might have a huge globe on his back and crawl from New York to Washington to protest environmental abuses.

None of that happened, but in the Fall of 2013 when he told me he might crawl up Manhattan in his father’s suit, I didn’t blink. It made sense and it was manageable. We talked about what it would all mean and agreed that it needed to be open to interpretation. We did set some parameters: only Broadway and maybe he was Crawling Home to his apartment in Washington Heights.

I missed the maiden voyage on Halloween 2013, so I was able to learn of the unfolding project like others on Robbie’s mailing list. At first he was just e-mailing the crawl diaries to friends, but I encouraged him to start a website—not facebook, not too public, but something you could find if you looked, a destination that could be shared, where the whole journey would be chronicled.

Robbie had two reliable wing men on the project and one of them was the writer and raconteur Teddy Jefferson who accompanied the crawler on the maiden voyage and took photos that remain iconic 19 crawls later. The other wing man was me. I relished the chance to revisit my early days as a documenter of live events; I videoed performances in the 80’s in downtown New York, and also shot weddings at that time, events that unfolded without second takes. I love that kind of high-stakes shooting.

For the early crawls I edited in-camera, setting up an additional challenge for myself. As we got deeper in, I tried different rigs, such as a pole-cam designed to float indifferently above the crowds (#5, #19) and alternative cameras to my regular Canon 5D, including s8mm (#6, #16) and a couple point-and-shoots. The first crawls, which took 45 minutes to an hour for a trek of ten blocks, would string out to about 20 minutes of footage. The video was never supposed to be the point of the piece, nor the sole record of it.

The Crawl was first and foremost a live event, and secondly, a written recollection of Robbie’s experience. Thirdly, it was documented in iconic stills that accumulated as the crawls continued. Only lastly was there the video, which depicted the time-based reality of the crawl: arduous and repetitious. The videos have a strange inexorable movement to them, in which the viewer can watch events unfold as they did on the day. There is much richness to be discovered by the careful observer: recurring characters, strange exchanges, narrative developments and so much visual irony in the vivid tapestry of the city.

Not far into the piece, some of the feedback on the web started pointing out that the presence of the camera was changing the crawl, dispelling the mystery. This was demonstrably true, as some witnesses would stare astounded at the crawler, then search for a camera to justify and contextualize the odd behavior. Once seen, the novelty of the sight was diminished: “Oh, they’re just making a movie.” From my point of view then, the crawl project became an examination of our relationship to media. If something is filmed, it is owned, controlled, demystified. If something is being videoed, it is explainable. So the presence of the camera negated the oddness of the image that we were creating. Maybe “indigenous people” are right: the camera steals the soul.

Of course at the same time, one of the most common responses to the strange Broadway Crawler by the people on the street was to video him. There must be countless hours of cell phone footage and still shots of the Crawler out there. This all lead to a discussion of what was the purest form of the crawl. Naturally we concluded that to crawl alone would be the real deal, but like a tree falling in the woods, undocumented, would then the crawl ever even have happened? It still seemed imperative that we capture images of this strange odyssey for posterity. And so we found ourselves in a fairly predictable 21st century dilemma. Defensively, I proposed rather early on that Robbie should crawl alone, at least once. There would be the written recollections after all, surely that would be enough.

It was ironic that one of the reasons Robbie didn’t crawl alone for some time is his wife and kid were afraid for him and hoped he would always have a wingman. And the other reason not clear to the web observer was the crawl was a communal experience between Robbie, the city and his wingmen. Performance art has many motivators and one in this case was a yearning to connect: with the city, with the web visitors and with the wingmen, fellow travelers in this strange ritual.

Eventually work took me out of town and eventually Robbie did crawl alone.

When we reunited in the Spring, with only a few crawls left, we started to think about shaping the raw footage more. One crawl we edited to a three-minute music video, a welcome change from the verité treatment of previous crawls. The next video employed the intimate sounds of the crawler recorded on a mic placed on Robbie’s lapel, an enhancement I’d been too lazy to employ earlier.

The final embellishment to the video portion of the project was a second cameraman, my son Jack who joined us on the penultimate crawl and got hooked. This brought in a new perspective to the shooting and by definition required a more refined edit. It so happened that this was perhaps the most boisterous, exuberant crawl of the entire project, the whole neighborhood along upper Broadway was bathed in the golden light of a summer’s eve, buzzing with activity. Without fanfare a tiny magical matador in a white suite appeared out of the crowd. That strange little man got on the crawler’s back and rode him like Don Quixote in a surrealist street play.

But neither video camera caught it—maybe we were changing batteries. There was much hemming and hawing about missing perhaps the most spectacular moment of the near-200 block performance piece, but I remained defiant: the video record was never the point of the project, only an adjunct. It captured some aspects but not all of what happened on those streets over the course of those eight months. Many web trawlers scanned the video for some confirmation of the fantastic claims that the little man rode upon our Crawler. But there was no evidence save for one lone still shot.

Perhaps because the presence of the video camera had been scrutinized by some web commentators early on, I relished that this essential image went undocumented in the video. It will exist more in the realm of mythos, more in keeping with the intangible aspect of he crawl. Let us just say that I did not want my part of the crawl to be the demystifying of it, and so my failure as a documentarian helped preserve something integral to the project. Though I love cinema, I recoil from the ubiquity of video replacing all the other means by which we memorialize and share our experiences.

The final crawl, which brings the crawler home, was a two-camera shoot edited with music and sound; a fitting end to the journey, where we finally allowed ourselves to infuse the documentation with some of the emotion we had accumulated on the way. And so, from the first crawl to the last, there was an evolution to the documentation, from cinema verité to some sort of refinement, as the narrative poignancy of the journey’s end asserted itself.

I always said to Robbie, as he sought to define what he was doing and why, the real act was in creating an image, the image of a figure crawling on hands and knees up the sidewalks of this city in this time in our political and cultural history, during these seasons of this particular year. And that image carries an emotional weight for those who encountered it in real life and for those who followed it on-line.

I’ll miss the crawl. It was a chance to support art for art’s sake. It’s been a while.

Add a comment