From Tom Efinger at The Dig It Post:

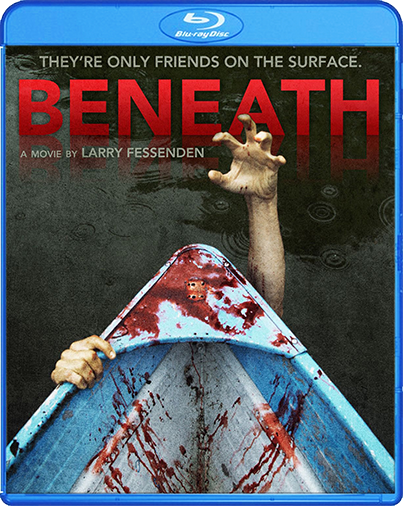

The film Beneath is the latest directing effort of writer, director, actor, and producer Larry Fessenden. Larry is a tried and true film maker; his acting credits include roles in movies like Scorsese’s Bringing Out The Dead, Jarmusch’s Broken Flowers, and The Brave One with Jodi Foster and Terrence Howard. He has directed several films, too: The Habit, Wendigo, The Last Winter, and Beneath are some of his main titles. He has also produced more films than you can shake a stick at. Larry is a real craftsman and his knowledge as a filmmaker informs every aspect of his films. What’s more, Larry Fessenden is an accomplished musician—who has the kind of ear and creative instincts that lead to great and compelling sound in movies.

Larry, you and I go way back. It might be fun to mention that we went to high school together and dabbled in film, theater and music back then. And now we recently finished the sound editing and mixing on Beneath, the third feature film, with you as director, that I have had the pleasure to work on. We have worked on about 12 to 15 feature film projects together with you as producer. I should also mention that the sound designer, Graham Reznick, who is someone we have both worked with extensively in the past several years, played a huge role in the sound for Beneath.

LF: I always like to tell people who I introduce to DigIt that you taught me to play the saxophone back in ninth grade when I was trying to figure out the instrument on my own. And I’ve watched DigIt grow over the years. These are my favorite relationships in show biz, the on-going ones.

Sound has always been a profound part of a movie for me. Before you could rent video, back in the bad-old 70’s, I would record movies off the TV and listen to them on cassette over and over and develop a relationship to the rhythm of the sound effects, talking and music—and I gained an appreciation for the potency of those elements playing together, even without picture.

I met Graham through Ti West and quickly came to understand his obsessive love and command of sound design. I immediately got him on to my project THE LAST WINTER, but he ended up being relegated to foley editor of the wendigo footfalls—of no small importance mind you. But in any case I hoped to work with Graham eventually and finally Beneath came along. Of course in the interim we have been at maybe half a dozen mixes together on the films I’ve produced.

How much do you think about sound when you are writing or working with the script prior to shooting?

LF: The way I work, I generally preconceive a film as I write the script. Even if I don’t write the original draft, eventually I get the script into a program where I can start breaking the whole story into beats, then individual shots. Somewhere in there the sound starts taking shape as well. A sense of place and the atmosphere are hugely important to a film, and I’m thinking about that stuff from the start. Also, like a lot of filmmakers, I start listening to music and gathering tracks that take me to that place where the film exists. So even at the start when I dream about my film, that dream has a full 5.1 mix.

Do you shoot differently when you are working towards a special sound moment?

LF: Every shot you take has an effect on the viewer, that is why the choice of lens, shutter speed, frame rate, exposure and movement all matter. At the same time, when planning a shot, I am often hearing how it will play as well. Often on set I bemuse my crew by making the sound of a shot: “Camera zooms in like this.” And then I’ll make a zoom sound. Then cut—and so on. Ti West does this too. It’s because film is rhythm, and rhythm suggests sounds.

On set I will occasionally assert that there will be sound design on a shot, and there is no need for sound, but the reality is it’s always good to take sound. At the same time, slating for sound can be infuriating and disruptive and I can get very impatient when trying to be spontaneous or candid or off the cuff. I am a big fan of tail slating, but so often people forget to call it. All of this speaks to having a crew that is working in sync with each other.

What were some of the specific challenges for sound on this project during the shooting?

LF: There were many. First of all, there was the acoustics of the water. You could literally hear people talking on shore even when you were in the middle of the lake. When the camera was low to the surface of the water the fan in the camera would echo and make all sorts of noise. And there was no hiding six lavaliere on the scantily clad teens either. We generally boomed from a little rubber raft and we had a lavaliere hidden in the boat so we had some choice in perspectives. Of course, it being summer, we had a lot of lawn mowers mowing throughout the day, and did I mention we were near a small airport? Then there were the dog walkers who were very pleasant except for the one who put a cowbell on his pooch. Took twenty minutes to hunt them down. Every day at 5:00 the local shooting range started up. You can still hear some of the shots on the soundtrack.

How did you begin to discuss the sound design with Graham, and how did that conversation evolve?

LF: Graham was actually on the shoot taking stills and he ran second unit the last week, so we were always talking about the sound, delighting in gathering creeks and noticing the noises of the lake and the boats and all the specifics of the location. Our sound man was excited to spend a day recording wild material for us, but as happens with low budget productions, someone in the ranks forbade him from doing the task to save money, and when I found out it was too late. This is always a tragedy. We recorded sounds months later in the country with the boats on dry land, but Lord, do it while you’re on set and in the moment. I was on another movie long ago and the sound guy said he would record lots of great wild tracks for us as soon as the shoot wrapped. He couldn’t have known his brother was going to murder their father, but that’s what happened so he never got to record the wild sound, he had to go home.

Thus, do it while you’re there on location, don’t delay. There may not be a “later”.

Graham had a wonderful reaction to the edit of the movie. He saw in my cutting and temp-audio that I wanted a heightened sound design. What we did was we sat down only once and “spotted” the film, took notes with time code on every single sound event we imagined in our heads. We were remarkably in synch in how we heard the film, where we wanted to play with perspectives, reverbs, drones, where the music would dominate and where the sound design would dominate. Some scenes were specifically shot with the sound in mind, as for example where the boat creeks fall into a nagging rhythm throughout the first voting scene. We established motifs throughout the film that form a subliminal substructure to everything the viewer hears. I always say, there is one picture that an audience responds to in a movie, but there are myriad sound tracks that are having a profound effect on the viewing experience.

Graham took the notes and went into his lab and built a great many tracks on his own—and then we watched it and made refinements in preparation for the mix. With some collaborators, I am more controlling, but with Graham, I felt in safe meticulous hands.

We had some fun mixing this show for sure. I find that we’re usually working with some very set ideas that you have going in, but we also leave room for experimentation. Can you comment on that?

LF: The great thing about genre films is you are working with subjective reality, and you are trying to put the audience in a place beyond their normal experience. Sound can be a critical method to transport the viewer. When we get into the mix room, no matter how much we’ve put in place, there are still opportunities to experience the film anew, and once the dialogue is refined and smoothed out, the real mix begins. Everything from choosing the reverbs that work in the room, to placing sounds in the 5.1 mix, to finding new enhancing sound effects comes up in the mix. No matter how much preparation there is beforehand, the mix is the time you are seeing all the elements together for the first time, and you want to be responsive to the fresh experience and keep crafting the material. For me, the best approach to all aspects of filmmaking is to show up with a plan and be prepared to verge from it if the spirit moves. Often the mix is the time that the music stems are first made available, and a lot of the mix is dealing with the balance between music and the sound design. For me, a good wind sound and a creek are as potent as a symphony orchestra. It’s all about crafting each moment.

What is your favorite aspect of the finished sound design and mix? What came as a surprise if anything?

LF: With sound, you can give weight, you can give immediacy, or existential indifference. In film school they often talk of the Kulachov theory of picture editing where they have an actor’s face staring and when you cut to a soup bowl the actor seems hungry, but when you cut to a coffin he seems sad and so on. Just think of all the things you can do with sound, just watching that same face and listening. That’s what I like about sound. It is a primary storyteller, every bit as much as picture. Of course on set all you care about is getting the image, sound gets trounced.

In Beneath, we tried to find aspects of telling a very traditional (dare I say clichéd?) story and find unexpected ways to present the material, as with when the first girl dies, we let the sounds drift away and we enter a dream state as the characters grapple with the strange reality that has just befallen them. Throughout the movie we delved into subjective points of view to indicate how the mind grapples with shock.

Do you find that directing the sound finishing is a difficult challenge or is it relatively easy after all the pressures of production?

LF: It is relatively easy only in that you are in a studio with your latte and pretzels, not off on location sweating it out. But there are the same restrictions on time that plague any endeavor with a budget. The thing about the mix, is it is truly the last stop on the long journey creating a film. If you are doing things right, it’s even after color correction, so this is the last chance to unify the film and make every beat flow to the next to create the impact, legibility and subtlety you are after. It is the end of the line, and therein lies tremendous pressure and the start of letting go.

See the original interview at http://thedigitpost.onsugar.com.

Add a comment